Category Archives: Styles

Earl Grey vs Black Tea

Man, I see these questions all the time on places like Quora. I used to get them in the tea shop all the time, too: What’s the difference between Earl Grey and black tea? How much caffeine is there in Earl Grey? What are the health benefits of Earl Grey compared to black tea?

Well, strap in and let’s see if I can cover it all in one article!

First, let’s get the basic facts on Earl Grey out of the way:

The original Earl Grey tea was black tea

Specifically, it was Earl Grey tea with bergamot oil added to it. (I know, that raises a new question. More on bergamot oil shortly…) Most, but not all, of the tea currently marketed as Earl Grey is still basically black tea with bergamot oil. That means the caffeine content is the same as black tea, the steep times are the same as black tea, and the color is the same as black tea. The aroma, however, is decidedly not black tea.

The origin story—who was this Earl Grey dude and why did he create this tea?—is one of the chapters in my book, Myths & Legends of Tea, volume 1. In short, Charles Grey II, Lord of Howick Hall, First Lord of the Admiralty, and soon to become the second Earl Grey, had really crappy water at Howick Hall. All of the limestone (just called “lime” by most at the time) in the water made the tea taste foul. Bergamot oil was the solution, as its strong aroma masked the bad stuff in the water.

Many people say Earl Grey smells “perfumey” because, well…

People have been using bergamot oil as an ingredient in perfumes and colognes for over 300 years now. Brands like Giorgio Armani, Christian Dior, Yves St. Laurent, Elizabeth Arden, Lancome, Calvin Klein, Oscar de la Renta, Donna Karan, Jimmy Choo, and many others put bergamot oil in various of their scents.

But what the heck is bergamot oil? Ready for the most unhelpful answer ever? It’s oil from a bergamot.

Okay, okay, I’ll explain. The bergamot, Citrus bergamia, is a citrus fruit native to southern Italy. It’s sometimes called a “bitter orange,” and to make your life just a little more complicated, it isn’t related at all to the bergamot herb, Thai bergamot, wild bergamot, or bergamot mint.

The bergamot oil is extracted from the rind of the fruit, and a little bit goes a long way! Typically, to make Earl Grey tea, the tea leaves are sprayed with a fine mist of bergamot oil and then packaged.

I keep referring to “most” Earl Grey teas

The Grey family never copyrighted the name Earl Grey for the tea, nor did they protect the formula legally. Although the original recipe was passed on to Twinings, anyone is free to make any variant they want and proudly brand it as Earl Grey.

There are Earl Grey teas out there using all manner of black teas as the base, not to mention all of the variants using green tea, white tea, herbal teas (“tisanes“), and other tea styles. I produced a number of these when I had my tea shop, including the oddly popular Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey, which was made with lapsang souchong, a smoked black tea from China.

Most, if not all, tea companies that make Earl Grey teas do try to use different names if they don’t use the classic black tea base. You’ll see names like Earl Green, Duke Grey, Creme Earl Grey, Earl Greyer (one of my favorite names), and many more.

And then there’s Lady Grey

Neither the Grey family nor Twinings has any protection on Earl Grey. Twinings does, however, have a trademark on “Lady Grey.” Unless you have bigger badder lawyers than Twinings (and the budget to pay them), I strongly recommend coming up with a different name for your take on Lady Grey. My version, which was black tea, bergamot oil, and lavender flowers, was called Lady Greystoke, named for Tarzan’s wife, Jane, after they got married and she took his family name and the title that came with it.

The dreaded topic of health benefits

My regular readers know that I rarely discuss health benefits of tea unless there’s some really solid science behind it. There are so many claims with zero data to back them up, so many flawed studies, so many misinterpreted studies. It’s really difficult to sort things out.

I really really wanted to say up at the very top that the health benefits of Earl Grey are exactly the same as the health benefits of plain black tea. But I just can’t.

On one hand, we have the aromatherapy and essential oil folks, who claim that bergamot oil helps to heal wounds, reduce inflammation, cure acne, promote hair growth, reduce stress, fight food poisoning, lower cholesterol, fight liver disease, reduce pain, and more.

On the other hand, we have medical evidence that bergamot oil can be a skin irritant for some people, causing blisters, pain, difficulty breathing, nausea, and vomiting. Also, it is a known phototoxin. Exposure to UV light (such as sunlight or tanning beds) after an aromatherapy session with bergamot oil can cause severe burn-like reactions, and the International Fragrance Association restricts the amount of bergamot oil that can be used in leave-on skin care products. Healthline even states that bergamot oil can be poisonous and should never be swallowed, although they are talking about the pure oil, not the small concentrations found in Earl Grey tea.

And so in conclusion

What most people call Earl Grey tea is just black tea with bergamot oil, which doesn’t change the looks (reddish-black), caffeine (probably 40mg per cup or so), or calories (about 2 per cup). It does, however, affect the smell and flavor. The health benefits may be different, but the amount of bergamot oil in a cup of Earl Grey tea is so tiny (less than .25 grams in my recipes) that it’s probably insignificant.

So enjoy your Earl Grey, treat it as nutritionally equivalent to black tea, and if you want to read the whole story, please buy a copy of my Myths & Legends of Tea book. I’d sure appreciate it!

Phong Sali 2011 Pu-erh from Laos

I first wrote this post in October of 2013. As I wrote back then, this was a pretty good sheng pu-erh, but it needed to be aged more. With much going on in life, I ended up putting it away in the back of the tea cabinet and forgetting about it. I pulled it out in 2019 or so and it was much better. It’s now 2024. The tea is 13 years old, and it’s excellent. I’ve been drinking infusions of it all day—as one can do with pu-erhs—and thoroughly enjoying it.

At World Tea Expo this year, I picked up a Laotian pu-erh (well, technically a “dark tea,” since it doesn’t come from Yunnan) from Kevin Gascoyne at Camellia Sinensis Tea House. I mentioned this in a blog post back in June, and said I’d be tasting it and writing about it “soon.” Well, since it’s a very young sheng (a.k.a. “raw”) pu-erh, I figured it wasn’t a big hurry, and “soon” ended up being October. Oh, well. Had to get all that Oktoberfest stuff out of the way first, I suppose.

Let me begin by explaining the label and the style of this tea.

That big “2011” on the label is the year that it was produced. Most pu-erh drinkers will tell you that a sheng pu-erh should be aged a minimum of five years before you drink it. I certainly won’t argue that the flavors improve and ripen as the tea ages, but in my humble opinion there’s nothing at all wrong with drinking a young sheng. I enjoyed the bit that I took off of this 357-gram beeng cha (pressed cake), but I’ll be saving most of it to drink as it matures. Will I be able to hang on another three years or more to drink the majority of it? That remains to be seen.

The words “Phong Sali” do not refer to the style of the tea, but to its origin. Phong Sali (or, more commonly, Phongsali) is the capital of Phongsali province in Laos. Technically, as I mentioned above, this tea style should be called by its generic name (“dark tea”) rather than its regional name (“pu-erh”), because it doesn’t come from the Yunnan province of China. Since the little town of Phongsali (population about 6,000) is only about 50 miles from Yunnan (which borders Phongsali province on the west and north), I think we can let that bit of terminology slide.

“Old tree” refers to the tea plants themselves. In most modern plantations, the tea is pruned to about waist height to make it easy to pick. In many older plantations, the tea has been allowed to grow into trees, which can reach heights of thirty feet or more. The particular tea trees from which this tea comes are over 100 years old.

Tasting the tea

Unwrapping the beeng cha provided my first close look at the tea. The leaves are quite large, and the cake is threaded with golden leaves that didn’t oxidize fully.

There is still enough moisture in the cake to make it fairly easy to flake off some tea from one edge. Shu pu-erh is often dried very hard, as it is “force fermented” so that it will be ready to drink earlier. Sheng pu-erh, on the other hand, needs a bit of moisture in it to continue fermenting over time. I decided to try it in a gaiwan rather than making a large cup, so that it would be easier to experiment with multiple infusions and smell/taste the tea as I went.

I used water just a bit cooler than boiling (water boils at 202°F at this altitude, and I used 195°F water for this tea), and roughly 7 or 8 grams of tea. Unscientific, I know, but I didn’t measure it. I steeped the tea for just a minute the first time, and got a delicate but flavorful cup of tea. The flavor is similar to a characteristic Chinese green tea (think dragonwell), but more woody and with a bit of spice.

The picture on the right shows the leaves, uncurled after the first steeping. They are large, supple, and fragrant.

That one-minute steep wasn’t really enough to hydrate the leaves, so I went for a second steep at 1:30 (pictured at left above). Much more flavor, but still extremely delicate compared to a fully-aged sheng pu-erh. I enjoyed a third and fourth steep, which had only minor changes in flavor, but was interrupted before I had a chance to keep going and see how it stood up to eight or ten steeps. An experiment for a quieter day, I suppose.

This tea is definitely worth enjoying a bit early, and I will definitely be coming back to it. Again, we’ll see how much survives to full maturity. I’m not very good at waiting!

Yerba mate

Let’s get this out of the way first: is it spelled yerba mate or maté? Normally, when words from other languages are adopted into English, their accent marks go away. In this case, it’s the other way around. In both Spanish and Portuguese, the word is spelled mate and pronounced MAH-tay. No accent mark is used, because it would shift the emphasis to the 2nd syllable. The word maté in Spanish means “killed.”

In the United States, people unfamiliar with the drink see “yerba mate” written on a jar in a tea shop and pronounce mate to rhyme with late. So it has become accepted in English to add the accent above the e just to help us pronounce the word right. Linguists call this a hypercorrection.

Yerba, on the other hand, is spelled consistently in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, but the pronunciation varies depending on where you are. As you move across South America, it shifts from YER-ba to JHER-ba.

Directly translated, a mate is a gourd, and yerba is an herb, so yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) is literally the herb you drink from a gourd. I don’t really care which way you spell (or pronounce) the word as long as you give this delicious drink a try!

Yerba mate is a species of holly that contains caffeine (not, as previously thought, some related molecule called mateine). It grows in Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, and is the caffeinated beverage of choice for many people who live in those countries.

In the U.S., mate is usually made like tea, with the leaves steeped in boiling water for a few minutes and then removed. This, however, isn’t the way Argentinian gauchos (cowboys) been drinking mate in South America for centuries.

The process uses four elements: dried yerba mate leaves, hot water, a gourd (mate), and a bombilla (straw). Bombilla is another word that varies in pronunciation in different parts of South America, ranging from BOM-bee-ya to BOM-beezh-a.

Drinking mate was a social time for the gauchos and still is throughout much of South America. You generally won’t find yerba mate served this way in a U.S. tea shop, because it’s darned near impossible to clean a natural gourd to health department standards.

- First, the host (known as the cebador), fills the gourd about 1/2 to 2/3 full of leaf. Yeah, that’s a lot of leaf, but we’ll get a lot of cups out of it!

- Next, the cebador shakes or taps the gourd at an angle to get the fine particles to settle to the bottom and the stems and large pieces to rise to the top, making a natural filter bed. Before pressing the bombilla against the leaves, dampening them with cool water helps to keep the filter bed in place.

- Finally, the cebador adds the warm water. The water is warm (around 60-70°C or 140-160°F) rather than boiling, because boiling water may cause the gourd to crack—and your lips simply won’t forgive you for drinking boiling water through a metal straw!

In most of the world’s ceremonies, the host goes last, always serving the guests first. The mate ceremony doesn’t work that way. That first gourd full of yerba mate is most likely to get little leaf particles in the bombilla, and can be bitter. So the cebador takes one for the team and drinks the first gourdful.

After polishing off the first round, the cebador adds more warm water and passes the gourd to the guest to his or her left. The guest empties the gourd completely (you share the gourd, not the drink!), being careful not to jiggle around the bombilla and upset the filter bed, and passes the gourd back to the cebador.

The process repeats, moving clockwise around the participants, with everyone getting a full gourd of yerba mate. A gourd full of leaves should last for at least 15 servings before it loses its flavor and becomes flat.

The Evolution of Taste

What was the first tea you tasted? If you’re American, it was probably a cheap teabag filled with black tea dust, probably steeped for a long time and possibly drowned in milk and sugar.

If you have a taste for adventure, you probably tried a few other things later on. Earl Grey, perhaps, or possibly a pot of nondescript green tea at the Chinese restaurant down the street. Then maybe — just maybe — you stopped into your Friendly Neighborhood Indie Tea Shop™ and had your mind blown by an amazing oolong or a mind-blowing pu-erh. Now you want to taste all the tea!

Congratulations, you would have been the perfect candidate to join the tea tasting club at my old shop (Phoenix Pearl Tea), but let’s leave that for another blog post.

Thankful to have left that cruddy old Lipton behind, you plow forth into the tea world. You taste exotic green teas like genmaicha (roasted rice tea), hōjicha (roasted green tea), and kukicha (twig tea). You savor delicate white teas like silver needle. You chase down both sides of the pu-erh spectrum, sampling rich complex sheng and deep earthy shu. You try the full range of oolongs, from buttery jade to crisp Wuyi. You might even be lucky enough to find a tea shop with a yellow tea. Wow.

But you’ve left the black teas behind, your impressions tainted from those teabags you drank back before you became enlightened.

Yesterday, I taught a tea class on the teas of China. In it, we tasted all of the major tea styles, and sampled our way through five prime tea-growing provinces (Anhui, Fujian, Jiangsu, Yunnan, and Zhejiang). There were oohs and ahs over the bai mudan white, the roasted tieguanyin (Iron Goddess of Mercy) oolong, and the longjing (dragonwell) green. But do you know what stopped everyone cold in their tracks? The black teas.

I pulled out my favorite Keemun mao feng. If you’ve never tried one of these, stop reading now, buy yourself a bag, and come back. Ready? Okay. Let’s continue.

It’s easy to fall in the trap of considering black tea the “cheap stuff” and all of the other varieties the “good stuff” (except for that pond scum the Chinese restaurant down the street thinks of as green tea, but we’ll just ignore those guys). Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Keemun mao feng has a lot going on. It’s rich and complex, lighter than you’d expect, and if you consider grocery-store-brand teabags representative of black tea, this stuff will open your eyes. The people in my class kept commenting on how many layers of flavor this tea has, on how it changes as you hold it on your tongue, and the subtle sweetness they picked up in this (completely unsweetened) cup of tea.

Note, by the way, the steeping instructions in my slide above. You may like yours steeped longer than the two minutes I recommend. That’s fine. I’m no tea Nazi. Drink it the way you like it.

Next, we tried a dian hong, also known as a Golden Yunnan. It flips you clear across the flavor spectrum, with that color in the glass saying “oolong” as the flavor says “black tea.”

If you’re at this point in your exploration of the tea world, congratulations! You’ve left the cheap black tea behind and opened yourself up to a whole world of other tea styles. Now it’s time to come back home to black teas. Try the two I talked about above. Explore the vast difference between India’s tea-growing regions by drinking a first-flush Darjeeling, a hearty Assam, and a rich “bitey” Nilgiri. Sample the Rift Valley teas from Kenya (the largest tea exporting country in the world). Island hop with some Java and Sumatra tea. Drink a liquid campfire with a steaming cup of lapsang souchong.

Once you’ve experienced the range of flavors, textures, terroirs, and aromas from top-notch loose-leaf black teas, you’re still not done. Now is the time to turn your newly-expanded palate loose on some blended teas, like high-end English Breakfast. Go back and taste some of the flavored black teas like Earl Grey. Play with some masala chai and some tea lattes (try a strong Java tea made with frothed vanilla soy milk!). Start experimenting with iced tea, brewing it strong and pouring it over ice.

You may decide that you’ve moved on from black tea and that’s great. Or you may just find that you’ve developed a whole new appreciation for that stuff that got you started on tea in the first place.

As I write this, I’m sipping on a 2017 1st flush Darjeeling from Glenburn estate. It’s very different from last year’s, when the picking was delayed by heavy late rains. You’d swear this was oolong tea. It’s extremely different from teas picked at that estate later in the year. I don’t know what (if anything) we’re going to end up with for a 2018 1st flush, as many of the estates in Darjeeling were left in horrible condition after this summer’s strikes, so if you have some Darjeeling tea you like, don’t waste it!

Tea Around the World

I came across a fascinating article the other day with pictures (and short captions) of tea as they drink it in 22 countries around the world. Obviously, picking one tea — and one style of drinking it — to represent an entire country is difficult, but they did an admirable job of it. What I appreciated, though, is that it got me thinking about the way we experience tea from other countries.

I was rather distressed that the caption they chose for the U.S. was:

Iced tea from the American South is usually prepared from bagged tea. In addition to tea bags and loose tea, powdered “instant iced tea mix” is available in stores.

Eek! As much as I enjoy a cup of iced tea on a hot day, I rarely stoop to tea bags, and never to “instant iced tea mix.” If you are one of my international readers (when I last checked, about half of this site’s visitors were outside the U.S.), please don’t judge us based on that article!

Despite that, the article made me think about something: When we experiment with the drinks from other countries, we usually prepare them our own way. Yerba mate, for example. The traditional method of making mate in Argentina, Uruguay, or Paraguay is in a gourd, with water that Americans would call “warm.” Americans trying out the drink usually make it just like a cup of tea, using boiling water in a cup or mug.

With tea, many of us would have difficulty drinking a cup of tea like they do in another country. Follow that link above and look at their description of Tibetan tea (#5 on the list). I don’t know about where you live, but here in Montana, I can’t easily lay my hands on yak butter.

Nonetheless, it’s a lot of fun to research how people eat and drink in other countries and try to duplicate the experience. Even if you’re not doing it exactly right at first, it makes you feel connected with other people and their cultures.

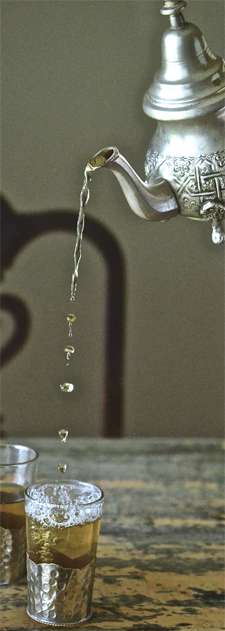

When my wife and I were dating, we discovered a Moroccan restaurant that we both loved in San Jose, California. They had fabulous food, belly dancers, authentic music, and — of course — Moroccan mint tea.

Kathy and I loved enjoyed watching them pour the tea as much as we enjoyed drinking it. We sat cross-legged on pillows around a low table. The server would place the ornate glasses — yes, glasses for hot tea — on the table and hold the metal teapot high in the air to pour the tea.

I am not a big fan of mint teas, generally, and I do not sweeten my tea, but I absolutely loved the tea at Menara (and no matter what my wife tells you, it had nothing to do with being distracted by the belly dancer).

When I made Moroccan mint tea at home, it never came out the same. There was always something off about the taste. I tried different blends, but just couldn’t duplicate the flavor. Then I decided to try duplicating the technique.

AHA!

Take a look at that picture to the right (a marvelously-staged and shot picture from chelle marie). Look closely at the glass. That, as it turns out, is what I was missing. Pouring the tea from a height does more than just look good; it aerates the tea, which changes the way it tastes and smells.

You’ll find the same thing with a well-whisked bowl of matcha (Japan), a traditionally-made cup of masala chai (India), a frothy-sweet boba tea (Taiwan), or a cold, refreshing Southern sweet tea (USA).

If there’s a tea shop or restaurant in your area that makes the kind of tea you want to try, get it there first. Otherwise, read a few blog posts, watch a few videos, check out a good book, and give it your best try.

Tea is more than just a beverage; it is a window into the cultures that consume it. Embrace the differences. Enjoy the differences. Enjoy the tea!

Jasmine Tea

Even purists who eschew “flavored” teas will often enjoy a cup of jasmine green tea. Perhaps it is because when you look at the loose tea, all you see is tea leaves; there are no visible indications that your tea leaves have been adulterated in any way. Perhaps it is because the affect of the jasmine in a well-made jasmine tea is delicate and subtle. Perhaps it is the rich history of jasmine teas.

Jasmine first made its way to China from Persia (now known as Iran) over 1,700 years ago, and it took hundreds of years before it was used to scent tea. Even then, it spread quite slowly, and it wasn’t until the Qing Dynasty, which began in 1644, that it became widespread.

The making of jasmine tea is quite different from typical flavored teas. Most flavored teas are either blends, where dry ingredients are mixed together, or tea leaves sprayed with flavor extracts, like Earl Grey with its bergamot oil. Jasmine tea, on the other hand, is scented rather than flavored.

In the traditional process, jasmine flowers are picked early in the morning, when the blossoms are still tightly rolled. Trays of processed and dried tea leaves (usually, but not always, green tea) are stacked in alternation with trays of jasmine. The trays have woven mesh or screens as bottoms, so as the jasmine blossoms open up and release their scent, it travels freely into the tea leaves over the course of about four hours.

The tea leaves pick up moisture from the flowers along with the jasmine scent, so they have to be re-dried before they can be packaged. In the finest quality jasmine teas, this scenting process may be repeated half a dozen times or more. The finished tea has no jasmine blossoms in it — only the scent that has transferred.

How you prepare a cup of jasmine tea depends on the base tea used. If it is made form a green tea, as most of them are, then you’ll want to use 175-185°F (80-85°C) water, and steep for three minutes or less. Using boiling water is a quick way to ruin a good cup of jasmine tea — or any other green tea, for that matter — by bringing out unwanted bitterness.

Grades of jasmine tea vary with the quality of the tea and the process used. One of the popular higher-end styles involves tea leaves that are tightly rolled, often known as “jasmine pearls.”

When drinking jasmine pearls, seven balls are placed in a small cup. Seven is considered good luck, so with jasmine pearls you don’t weigh them out or measure them in a tablespoon. Each rolled ball contains two leaves attached to a bud, which will slowly unfurl when the hot water is added.

Unlike most loose tea, jasmine pearls are infused right in the cup with no screens or filters, and you don’t remove them before drinking. The unbroken leaves assure that if you sip carefully, you won’t get a mouthful of leaf. If you’re drinking jasmine pearls with friends, the host should make sure that there’s always more hot water available to keep refilling the cups.

Jasmine blossoms certainly aren’t the only flowers used to scent tea — I’ve written about Vietnamese Lotus Tea, for example — but jasmine is definitely the best-known and most popular.

Scottish Breakfast Tea

Have you ever sat down to a cup of hot, energizing breakfast tea and wondered what the heck makes it a breakfast blend? You never see anyone selling lunch teas or dinner teas. Why breakfast tea? And what’s the difference between Scottish, Irish, and English breakfast teas? Let me explain!

When we first get up in the morning, most of us aren’t in the mood for something delicate, flowery, and subtle. We want caffeine and we want it now! And by golly, we want to be able to taste it! Breakfast, as any nutritionist will tell you, is the most important meal of the day. You probably haven’t eaten in ten or twelve hours, and you need energy for your morning work. A full-flavored hearty breakfast will overwhelm the taste of a white tea or a jasmine tea, so Americans and Europeans, unlike our Eastern friends, usually go for a black tea (or perhaps a heavily-oxidized oolong) with our breakfast. This is the origin of the “breakfast tea.”

Breakfast teas in the U.K. were originally Chinese tea. When supplies from China were threatened and the British East India Company established tea plantations in Assam, those Indian teas began to replace the Chinese teas at breakfast, and that’s also when they started to become blends rather than straight tea. One of the words you’ll often hear to describe breakfast teas is “malty.” That flavor comes from the Assam teas. There isn’t a standard formula for any breakfast tea, and no two tea producers will agree on the perfect teas or the perfect blend percentages. Generally, though, the Assam is blended with a strong traditional black tea from Sri Lanka (a Ceylon tea) or Kenya. Some blends are simple combinations of two base teas; some are complex combinations of four or five.

There also isn’t a standard for strength. Generally, though, you can assume that Scottish and Irish breakfast teas will be stronger than English breakfast teas, and when you’re in the U.K., you can count on all of them being served with milk.

An American might start the day with biscuits and sausage gravy with an egg on top—or perhaps a big stack of pancakes. A Scotsman, however, may sit down to a “full breakfast,” which would include eggs, bacon (what an American would call “Canadian bacon” and a Canadian would call “back bacon”), toast, sausage, black pudding, grilled tomato, and—if he’s lucky—some haggis and tattie scones. No wimpy tea will work with a meal like that! It calls for a full pot of Scottish breakfast tea!

At my tea bar, I started out with stock blends for all three breakfast teas. Soon, though, my Scottish heritage gave me the urge to experiment. I’ve known the folks from the Khongea Estate in Assam for a while, and they have a variety that made the perfect start. Lots of malty flavor, lots of caffeine, but not too much astringency. Unlike my ancestors, you see, I don’t put milk in my tea, so I look for less bitterness than most Scots.

After playing around with other teas, I settled on another estate-grown variety as the second ingredient. It’s a fairly high-altitude tea that grows near the base of Mount Kenya. It adds strength and complexity to the Assam, and I decided no other ingredients were needed. Once I was happy with the flavor, I needed a name. Scottish Breakfast Tea is just a bit too boring for me, so I called it “Gary’s Kilty Pleasure.”

For the curious, that’s my plaid in the logo: the Clan Gunn weathered tartan.

I got a very big surprise from this tea. American tea tastes run toward flavored teas. The majority of sales at my tea bar are Earl Grey, masala chai, fruity blends, and the like. Despite that, Gary’s Kilty Pleasure has remained one of the top five sellers for four straight years, out of a field of well over 100 loose teas. The most common comment I get back is that it goes well with milk, but it is perfectly good without—and that makes me happy!

So whether you choose my Scottish breakfast tea or a blend from your favorite supplier, brew it up strong with a hearty breakfast, and get your day off to a great start!

I have started adding a paragraph at the end of each blog post describing the tea I was drinking when I wrote the post. It seems kind of silly at the end of this one! Come on, people. What do you THINK I was drinking?

Comparing Apples and … Tea?

On our way back from a book conference in Tacoma, Washington, my wife pointed out that we were passing an awful lot of stands selling fresh apples. Since it was the season, we picked a big place and stopped.

What an experience!

I knew there were different varieties of apples (Granny Smith, Red Delicious, Fuji…), but I had no idea how many there were. Different colors, sizes, and flavors. Apples that are great for munching, others great for cider, and still others great for applesauce. There are over 7,500 cultivars of apple, and even though this farm had fewer than 50 of them, I was completely and utterly overwhelmed.

And then the epiphany hit me: The way I felt looking at these apples, that deer-in-the-headlights look on my face, was just what I’ve seen on people’s faces the first time they walk into my tea bar. As an aficionado, I walk into a tea shop and start hunting for things I’ve never tried, strange varieties I’ve heard of but never seen, and old favorites that they may bring in from a different source than I do. To a newcomer, though, those 150 jars behind the tea bar might as well be full of pixie dust as tea.

The way the apple farmer led us through our selection is different from the way we guide people at the tea bar, but the general philosophy is the same. His job, like our job, is to help a customer pick something that will make them happy. if you’re going to be making apple butter, he’s eager to help you find just the right apples and suggest just the right procedure. That way, you’ll be back the next time you need apples. We do the same with tea.

Sometimes, we have the customer who knows exactly what they want. “Do you have a jasmine green tea?” they’ll ask. Or, “Can I get an English Breakfast Tea with a spot of milk?” Those folks are easy.

We also have the people who have a general idea of what they’re looking for, but they’re eager to experiment. “I’m looking for a cup of strong tea. What’s the difference between your Rwandan and your Malawi black teas?”

But the challenge comes when somebody has no idea what they’re after. That’s when we play a kind of twenty-questions game.

Q. Are you looking for a straight tea or something flavored?

A. Oh, just straight tea, I think.

Q. Do you like black tea? Green tea? Oolong?

A. I like green tea.

Q. Do you prefer the grassy Japanese styles or the pan-fired Chinese styles?

A. I had a really good Japanese tea one time that tasted really nutty. They called it green tea but the leaves were brown.

Q. Was it roasted? Does the name Houjicha sound familiar?

A. I’m not sure.

Q. Here. Smell this.

A. That smells great! I’ll have a cup of that!

This kind of conversation is what it takes to guide someone to something new. Hopefully something they’ll like so much that they’ll keep coming back for more. To expedite the process, we’re reorganizing the teas behind the bar.

On one side, we’re putting straight tea, and some pure herbs and related tisanes like rooibos, honeybush, yerba mate, guayusa, and so forth. They’re organized first by style, so all of the white teas are together and all of the pu-erh teas are together. Within that grouping, they’re organized by origin: Ceylons, Assams, Kenyans, and so forth.

The other side has the flavored and scented teas, and it’s organized quite differently. Most people looking for a mango tea really couldn’t care less whether the base is white tea or green tea. All they care about is whether it has caffeine (and whether it tastes like mango, of course). To that end, the flavored side is grouped by flavor profiles: minty, fruity, flowery, and so forth. All of the berry teas are together, all of the masala chai is together, all of the Earl Grey is together, etc.

Hopefully, this will be a big help to people who think visually. They will be able to scan the jars and narrow in on something they like. When we’re done, we’ll post some pictures.

In the meantime, if you are a tea retailer, keep on talking to people. If you’re a tea consumer, keep on asking questions!

Gold Nugget Pu-Erh

We went to Portland, Oregon for a book show last week. I was there to roll out my new book (Who Pooped in the Cascades?) and to take a look at interesting books from other authors — not to mention a whole lot of networking. While we were there, I took some time out to meet fellow tea blogger Geoffrey Norman for a cup or three of tea (and maybe a beer or two, but that’s completely beside the point). I told Geoffrey to pick his favorite tea shop in Portland and take me there. He chose The Jasmine Pearl on NE 22nd, and the adventure went from there…

My daughter, Gwen, accompanied Geoffrey and I to the shop, and we entered to the wondrous smell of tea blending and brewing. We met the owners and several other staff members, and then settled in to browse.

As I typically do when entering a new tea shop, I explored their tea list to see what they had available. They had the usual selection of flavored teas & scented tea (Earl Grey, Moroccan mint, jasmine pearls…) and old standbys (tieguanyin, English breakfast, gunpowder green…). They also had some very interesting-looking varietals and single-source teas, including kukicha, dong ding oolong, and Gaba oolong.

After we looked around a bit, they informed us that tasting was free and pretty much everything was available to taste. One of the staff pulled out a couple of gaiwans, along with cups, strainers, and other related accoutrements, and asked where we’d like to start.

We started with the kukicha and dong ding oolong, and they were both good. The Gaba oolong, on the other hand, was an absolutely wonderful, and it has a great story behind it, too — but that’s for another blog post.

After going through the oolongs, Gwen chose to try her favorite black tea, a lapsang souchong, and she ended up loving it.

I, on the other hand, wanted to try pu-erhs.

I asked what was their richest, earthiest, most complex pu-erh. She immediately guided me to the Gold Nugget. Not to spoil the ending to this story, but I ended up buying some to bring home.

It looks like any other brick of pu-erh when it’s wrapped up like that, but when the wrapper comes off, it gets different. It seems that it has the name “Gold Nugget” for a reason.

Most pressed tea is made with larger leaf varietals of Camellia sinensis, and the leaves are laid out rather randomly. This requires flaking off bits of the tea with a pu-erh knife or some similar implement. This shu (“ripe”) pu-erh uses whole leaves, but they are rolled up like an oolong or gunpowder tea first. These “nuggets” are then pressed into the cake.

When I’m comparing tea, I like to keep the variables to a minimum. The little pile of nuggets in the picture weighs 7 grams. I put them in my infuser and did a 10-second wash with boiling water, which I drained out completely. Then I added 16 ounces of boiling water and let it steep for three minutes.

To me, three minutes is a long steep time for a shu pu-erh. When I’m drinking my favorite pu-erhs, I usually go for more like 90 seconds. Our first taste of this in the tea bar, on the other hand, was steeped for five minutes, because I told her I liked it strong.

I do, indeed, like it strong, but after steeping for five minutes, the flavors are rather muddled together. That’s why my first pass at home was for three.

The result was exactly what I had asked for: rich and complex are great adjectives for this tea. This is pretty much the polar opposite of the last pu-erh I blogged about. I will, however, be using longer steep times than usual for my first infusion, simply because those nuggets are rolled so tight that it takes a couple of infusions to open them up all the way.

All in all, it was a great trip, and I came back with some great tea, lots and lots of autographed books, and some fond memories. After the tea tasting, we met my wife at a sushi restaurant and had some wonderful sushi rolls and interesting beers. I wouldn’t say Geoff knows as much about beer as he does about tea, but I think we’ll be having some future conversations about the differences and similarities in teas and beers.