Category Archives: Styles

Chanoyu: The Way of Tea

This is part two of my article on the Japanese stop of our World Tea Tasting Tour. Part one was posted a few days ago.

The Japanese tea ceremony has been around for a very long time, but it was solidified into its current form in the 1500s by a man named Sen no Rikyū. He was an adherent of a philosophy called wabi-sabi, which honors and treasures simplicity, transience, asymmetry, and finding the beauty in imperfection. Rikyū applied this to the tea ceremony, developing what became known as chanoyu: the Way of Tea.

He removed unnecessary ornamentation from tearooms, typically reducing the decor to a single scroll on the wall and a flower arrangement designed to harmonize with the garden outside. Everything else in the room was functional. Chanoyu teaches four fundamental principles known as wa kei sei jaku, intended to be not only the core of the tea ceremony, but a representation of the principles to incorporate into daily life.

Wa (harmony) was his ultimate ideal. From harmony comes peace. Guest and host should be in harmony and man should strive for harmony with nature, rather than attempting to dominate nature.

Kei (respect) allows people to accept and understand others even when you do not agree with them. In a tea ceremony the guest must respect the host and the host must respect the guest, making them equals. The simplest vase should be treated as well as the most expensive, and the same politeness and purity of heart should be extended to your servant as to your master.

Sei (purity) is a part of the ritual of the tea ceremony, cleaning everything beforehand and wiping each vessel with a special cloth before using it. But that is only an outward reflection of the purity of the heart and soul that brings the harmony and respect. In accordance with wabi-cha, imperfection was to be prized here as well. To Rikyū, the ultimate expression of purity was the garden after he spent hours grooming it and several leaves settled randomly on the assiduously manicured walkway.

Finally, Jaku (tranquility) is the ultimate goal of enlightenment and selflessness. It is also the fresh beginning as you go back with fresh perspective to examine the way you have chosen to implement harmony, respect, and purity into your life.

There is a long list of implements that are used in the preparation of matcha, which is the powdered tea used in the tea ceremony. The four that I concentrated on in this class were the bowl, scoop, whisk, and caddy. It could be argued that others are as important, or even more important, but I chose to focus on the ones that are used at home when you make matcha, even if you are not participating in a tea ceremony. The link in the slide above is a great place to learn all about the ceremony itself, and the site contains a detailed list of chanoyu utensils.

In preparing matcha, the bamboo scoop is used to take tea powder and place it in the bowl. After adding water, the whisk is used not only to mix the powder, but to aerate the mixture, leaving it slightly frothy.

Of all of the tools of chanoyu, the bowl is probably the most personal.

We were lucky enough to have Karin Solberg, who created the matcha bowls we sell at our store, talk about the process of creating and decorating the bowls. Karin has done some lovely work, and we enjoyed learning from her. There is a picture showing some of her bowls in part 1 of this article.

I have said many times before that tea is a very personal thing. Nobody can tell you what tastes good to you. The “right” way for me to enjoy a particular tea could be quite different than the “right” way for you to enjoy that same tea. To Rikyū, however, the tea ceremony was not about what made your matcha taste the best. It was all about using the ritual to clear your mind and help you to see things more clearly. It was about achieving harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility.

Outside of the ceremony, however, I would argue that your way of relaxing is the right way of relaxing, whether it means sitting on your front porch with a steaming hot cup of Earl Grey, preparing a delicate silver needle tea to enjoy with a friend, or laying back in the bathtub with a fragrant jasmine green tea. Tea should be a pleasure, not a chore, and the ceremony is about sharing that pleasure with your friends and guests.

If you live in the area and were unable to attend this session, I sure hope to see you at one of our future stops on our World Tea Tasting Tour. Follow the link for the full schedule, and follow us on Facebook or Twitter for regular updates (the event invitations on Facebook have the most information).

Japan – Bancha to Matcha: Stop 4 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

We’re very excited to be working with resident artist Karin Solberg from the Red Lodge Clay Center, and we are featuring some of her matcha bowls in the store, and she came in to talk about them at this stop in the tour.

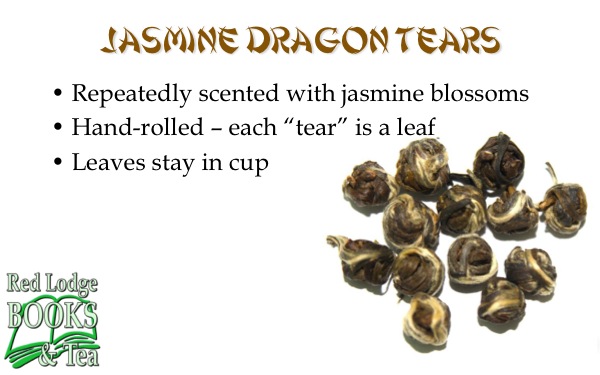

The teas we tasted were:

- Organic Sencha

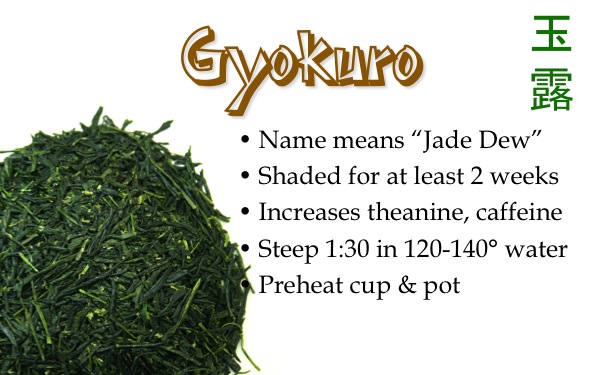

- Gyokuro

- Organic Houjicha (roasted green tea)

- Organic Genmaicha (toasted rice tea)

- Organic Matcha

- Kukicha (“twig tea”)

- Bancha (“coarse sencha”)

- Sencha (“decocted tea”)

- Gyokuro (“jade dew”)

It’s Always Tea Time in India: Stop 3 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

India: the world’s second-largest producer of tea. Our third stop on the tasting tour explored the world of Indian estate teas, focusing on three large and well-known tea regions in the country: Darjeeling, Assam, and Nilgiri. Red Lodge Books & Tea imports directly from estates in Darjeeling and Assam. We compared single-source estate teas (think single-malt Scotch) from Glenburn, Khongea, and Tiger Hill estates to a blended 2nd-flush Darjeeling using tea from Marybong, Lingia, and Chamong estates.

We also explored the rich history of tea in India, from the British East India Company through the modern independent tea industry, and looked at the rating system used for Indian teas, which I wrote about last month here on “Tea With Gary”

The teas we tasted were:

- 1st Flush Darjeeling FTGFOP-1 — Glenburn Estate

- Organic 2nd Flush Darjeeling — Marybong, Lingia & Chamong Estates

- Autumn Crescendo Darjeeling FTGFOP-1 — Glenburn Estate

- Green Darjeeling — Glenburn Estate

- Assam Leaf — Khongea Estate

- Nilgiri FOP Clonal — Tiger Hill Estate

As I mentioned above, India is the 2nd largest producer of tea in the world, but 70% of their tea is consumed domestically, so they don’t play as big a role in the export market as countries like Kenya.

Darjeeling

Darjeeling is the northernmost district in North Bengal. Of the 1,842,000 people who live there, over 52,000 make their living through tea. Darjeeling tea, often called the Champagne of Teas, is made from Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, the Chinese varietal of the tea plant, unlike tea from most of the rest of India, which is made from their native Camellia sinensis var. assamica.

Despite the generalization that black tea is always 100% oxidized (often incorrectly called “fermented”), most Darjeeling black teas are, like oolongs, not completely oxidized. While Darjeeling is known mostly for its black tea, there are oolongs and green teas produced there.

To be called “Darjeeling,” the tea must be produced at one of the 87 tea gardens (estates) in the Darjeeling district. Alas, the majority of tea sold with that name is not actually Darjeeling. Each year, the district produces about 10,000 tonnes of tea, and 40,000 tonnes show up for sale on the global market. In other words, 3/4 of the “Darjeeling” tea in the stores isn’t Darjeeling! That’s why we choose reputable suppliers at our store, buying most of it directly from the estate.

Darjeeling tea changes dramatically by the picking season, which is why we chose three different black Darjeelings for this tasting.

1st Flush Darjeeling FTGFOP-1

The first tea we tasted was a first-flush Darjeeling from the Glenburn Estate, where we get most of our Darjeeling teas. Glenburn was started by a Scottish tea company in 1859, but has now been in the Prakash family for four generations. The estate is 1,875 acres (with 700 under tea), and produces 275,000 pounds of tea per year. They are located at 3,200 feet altitude and get 64-79 inches of rain per year. Glenburn employs 893 permanent workers, plus temporary workers during the picking season.

2nd Flush “Muscatel” Darjeeling

Our next tea was an organic 2nd flush blend by Rishi, using Darjeeling teas from Marybong, Lingia & Chamong Estates. It was specifically blended to bring out the characteristic “muscatel” flavor and aroma associated with second-flush Darjeelings.

Autumn Crescendo Darjeeling FTGFOP-1

For the third tea, we went back to Glenburn and selected an autumn-picked tea. Unlike the first two, we steeped this using full boiling water for three minutes, bringing out the undertones one might otherwise miss.

Green Darjeeling

To wrap up the Darjeeling teas, we tasted a green Darjeeling from last fall. It’s an interesting hybrid of Chinese varietal and processing methodology blended with Indian terroir.

Assam

Assam is a state in northeast India with a population of over 31 million and an area of over 30,000 square miles. If Darjeeling is the champagne of tea, then Assam would be the single malt Scotch of tea. Hearty and malty, this lowland-grown tea comes from the assamica varietal of the tea plant.

Assam Leaf Tea

The Assam tea that we tasted is from the Khongea Estate, which has 1,200 acres of land with 1,100 of that under tea. Sitting at 300 feet altitude, the estate gets 150-200 inches of rain per year, making drainage very important. They employ 1,202 permanent workers (again, more during picking), and produce 2,640 pounds of tea per year.

Since Assam tea is frequently used in breakfast blends, we tasted this one with nothing added and then with milk, as most English tea drinkers (and many Indian tea drinkers) prefer.

Nilgiri

Nilgiri is the westernmost district of the state of Tamil Natu. It is smaller (950 square miles) and less populated (735,000 people) than Darjeeling, and quite high elevation, with tea growing between 6,500 and 8,500 feet altitude.

Tiger Hill Nilgiri FOP Clonal

The tea that we chose from Nilgiri comes from the Tiger Hill Estate in the Nilgiris (the “Blue Mountains” for which the district is named). They have 640 acres under cultivation, almost all of which is “clonal,” meaning that it was grafted onto other rootstock from a few mother plants. Tiger Hill has been producing tea since 1971.

This was the third stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from last month.

Tea. Earl Grey. Hot: Stop 2 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Update: The story of the origin of Earl Grey tea is one of the chapters in my book, Myths & Legends of Tea. Check it out!

England may not grow many tea plants, but the United Kingdom has had a massive impact on the development and popularization of tea since the 1660s. Our second stop on the Red Lodge Books & Tea World Tea Tasting Tour explored the world of Earl Grey tea, from the Right Honourable Charles Grey (for whom Earl Grey tea is named) to Star Trek TNG’s Captain Jean-Luc Picard. Earl Grey isn’t a single tea, but a broad range of styles. We carry nine different Earl Greys, of which over half are our own house blends, made right here in Red Lodge. The teas we tasted were:

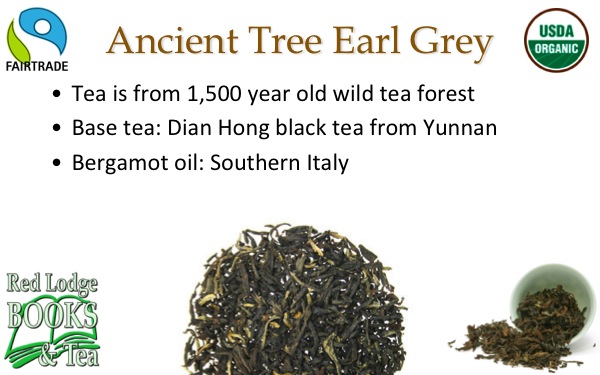

- Organic Ancient Tree Earl Grey

- Lady Greystoke

- Jasmine Earl Green

- Coyotes of the Purple Sage

- Fifty Shades of Earl Grey

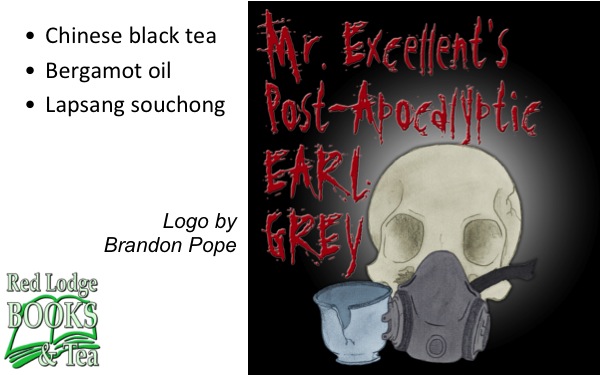

- Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey

We started out with a discussion of the history of Earl Grey tea. The common myth is that the tea blend was presented to Charles, the 2nd Earl Grey by a Chinese mandarin after Charles (or one of his men) saved the life of the mandarin’s son on a trip to China. In reality, Charles never set foot in China, and the history has a more mundane beginning. The Earl lived at Howick Hall, which had a high lime (calcium) content in its water. This gave his tea an off-flavor and he (or possibly Lady Grey, depending on who’s telling the story) consulted a tea expert for advice. This tea expert — possibly a Chinese mandarin, we don’t know — came up with the idea of adding the oil of the bergamot orange (Citrus bergamia) to the tea. This is what was served in Howick Hall, and the formula was eventually presented to Twinings by the Earl and it became one of their regular offerings. Twinings changed the formula a couple of years ago, but that’s another story. Before we leave the subject of bergamot, by the way, the word is Italian, not French, so the “T” at the end is pronounced. I have heard a lot of tea people talk about “bergamoh,” but it is actually pronounced just the way it is spelled. Tea purists who scoff at Earl Grey often use the word “perfumey” to describe it. There’s a reason for that. By some estimates, as much as half of women’s perfumes contain bergamot oil, and about a third of men’s fragrances. The first Earl Grey that we tasted is Ancient Tree Earl Grey from Rishi — a wonderful blend that does quite well in our tea bar. This amazing tea won “Best Earl Grey Tea” at the 2008 World Tea Championship. Next, we moved on to a house blend called Lady Greystoke. This is my take on lavender/vanilla Earl Grey, a blend which many tea shops would call Lady Grey, despite the trademark violation. Lady Grey tea is named for Mary Elizabeth Grey, the wife of Lord Charles, 2nd Earl Grey. Our Lady Greystoke is named for Jane Porter, who married Tarzan to become Lady Jane Greystoke (the full story is in an earlier blog post). For people that enjoy the bergamot, but want a milder tea, many shops offer an Earl Green or Earl White, and perhaps a caffeine-free Earl Red made from rooibos (yes, we have all three of those). For a different twist, we offered up a Jasmine Earl Green. Lightly perfumed with both with jasmine blossom and bergamot oil, it’s the most delicate of the teas we tasted. Next, we come to a popular blend of ours that really captures the character of the American West: a sage-based Earl Grey we call Coyotes of the Purple Sage. I know, it sounds rather strange, but the flavor mix really works. The literary allusion in this one comes from Zane Grey’s book, Riders of the Purple Sage. Yes, it’s a Zane Grey Earl Grey! For the story of the logo and blend, see my earlier blog post about it. The next tea also has a book theme — you can tell we have a combination tea bar and bookstore — but I’m not going to call this one a “literary” allusion, as nobody would refer to the Fifty Shades of Grey books as “literature.” I came up with the blend just for fun, with lots of punny references to the book, ranging from tea’s color (black and blue) to the rich flavor and overpowering bergamot. It actually ended up being quite tasty, and we’ve been selling quite a bit of it. We wrapped up with a signature house blend that’s completely different — a lapsang souchong-based Earl Grey that we call Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey. The full story of that tea has already been told here, so I won’t repeat it. If you live in the area and were unable to attend this session, I sure hope to see you at one of our future stops on our World Tea Tasting Tour. Follow the link for the full schedule, and follow us on Facebook for regular updates (the event invitations on Facebook have the most information). Let us close with a short video explaining the proper way to order a cup of Earl Grey tea:

Fun Blends: Terracotta Army Chocolate Pu–erh

My wife, Kathy, is a chocoholic who loves tea. She has tried chocolate tea blends from various companies, and decided that she’s not a fan of chocolate tea blends using mild-flavored tea. She likes to be able to taste the chocolate and the tea.

Gwen and Kathy and I experimented and came up with a blend based on a loose-leaf shu (ripe) pu-erh blended with cocoa nibs and vanilla. It was a struggle getting the balance just right, but the result was so good, we decided to give it a permanent home on the tea bar’s menu. After struggling for a while to come up with a name reflecting its Chinese origins: Terracotta Army Chocolate Pu-erh.

The Logo

I love having fun with tea logos. As I’ve mentioned before (see list below), a series of local artists have been creating logos for our house blends. This one was produced by artist (and art history professor) Kory Rountree:

We love that Kory started with one of the soldiers in the real Terracotta Army, made him chocolate, and gave him a cup of tea. He actually provided two logos for us to choose between. We picked the one above because it is clear, simple, and easy to identify even at small sizes. I actually prefer the alternative (shown below), but it’s just too complex to put on a little tea label.

The details are what really make this one. Note the eyes on the soldier above and left of the chocolate soldier. You can almost hear him thinking “Yummy!” The one above and to the right has a similar, but more subtle expression. It’s not obvious at first glance, but if you look closely, the soldier to the right of the chocolate fellow is holding a piece of the melted/broken chocolate arm in one hand, and a cup of chocolate pu-erh tea in the other.

Thank you, Kory! Another awesome logo for the collection!

This is the latest in a collection of labels I’ve written about here before:

Far Too Good For Ordinary People

Part of the fun of the tea business is the names. The names of the teas themselves are wonderful — from classics like Iron Goddess of Mercy to house blends like Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey — but the industry terminology is fun as well. Let’s take the “orange pekoe” grading system used for black teas from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and India.

Part of the fun of the tea business is the names. The names of the teas themselves are wonderful — from classics like Iron Goddess of Mercy to house blends like Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey — but the industry terminology is fun as well. Let’s take the “orange pekoe” grading system used for black teas from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and India.

I can’t count the number of times someone has come into the tea bar telling me they like flavored teas. “You know, something like that Orange Pekoe stuff.”

“Actually,” I have to explain, “that’s not a style of tea, but a grade. And it has no flavorings at all. Nope. No orange in it.”

What I generally don’t go on to explain is how that whole pekoe grading system works. Let’s start with the words “orange” and “pekoe.” A pekoe is a tea bud, the unopened leaf at the very tip of a branch. A pekoe tea, then, would contain the buds and smallest leaves adjacent to the buds. To further confuse matters, the word “pekoe” in grading tea doesn’t mean quite the same thing as it means when speaking of tea buds. We’ll get to that in a moment.

“Orange,” as I mentioned above, has nothing to do with fruit. What it does actually mean is open to debate. It could refer to the color of the oxidized leaves. It could refer to the color of the brewed tea. It could refer to the Dutch royal family (the House of Orange). All that really matters is that in tea grading, any whole-leaf black tea qualifies as an Orange Pekoe.

So what about all those other letters? The joke in the tea business is that FTGFOP stands for “Far Too Good For Ordinary People.” In reality, it stands for “Fine (or Finest) Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe.” Referring to a grade of tea as the “finest” isn’t good enough, of course, so there are actually several grades above that. Here are the basic grades:

- OP (Orange Pekoe): A whole-leaf black tea.

- FOP (Flowery Orange Pekoe): Long leaves with some tips (pekoes).

- GFOP (Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): An FOP with more tips.

- TGFOP (Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): A GFOP with a whole lot of tips.

- FTGFOP (Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): Traditionally the highest-quality grade of black tea.

- SFTGFOP (Special Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): Sorry, we needed one more grade.

For the true connoisseur, a grading system can never have fine enough gradations, so you can also elevate each of these grades another half-point by adding the number “1” after it. Thus, despite the industry joke, there are three grades of tea better than FTGFOP (FTGFOP-1, SFTGFOP, and SFTGFOP-1).

Let me reinforce an important point here: this grading system is used only for black teas, and only in a few countries. China, for example, rarely grades its teas using this system, although Kenya is doing more of it as their teas increase in quality.

Are there lower grades?

I thought you’d never ask.

The majority of tea consumed in the U.S. and U.K. is in teabags. In a traditional teabag, there’s little room for the hot water to circulate or the leaves to expand as they absorb water. The solution? Break those leaves into smaller pieces. That exposes more of the surface area of the leaf to water and allows more tea (by weight) to fit into a smaller area.

OP-grade teas use whole leaves. There is a series of grades below OP that include the letter B for “Broken.” BOP (Broken Orange Pekoe), FBOP, GBOP, and so on. There are also a couple of broken grades below BOP, including BP (Broken Pekoe) and BT (Broken Tea).

So that’s what’s used in teabags? Nope. Let’s drop another grade.

After the processing facility has sorted out all of the Pekoe and Broken Pekoe grades, what’s left is known as “fannings.” Grades like PF (Pekoe Fannings), FOF (Flowery Orange Fannings), and TGFOF (Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Fannings). These are the grades used in most decent-quality teabags (high-end teabags may use whole-leaf teas, typically in a sachet-style bag).

“Decent-quality teabags?” I hear you cry. “Are you implying there’s another grade below fannings?”

Yes. Yes I am.

The smallest-sized particles of tea — too small to be fannings — are called “dust.” There are different grades of dust, of course, depending on the tea leaves they come from. You may encounter PD (Pekoe Dust), GD (Golden Dust), FD (Fine Dust), and others. Typically, though, grades like that don’t make it onto commercial packaging.

So these lower grades suck?

No, I didn’t say that.

Fannings from an extraordinary tea will produce a much better drink than whole leaves from a mediocre tea. There are a lot of factors to take into consideration, but the number one factor is your own preferences. As I’ve said before on this blog, I’m not a tea Nazi. It won’t hurt my feelings a bit if you prefer the cheapest grade of Lipton teabags to my shop’s whole-leaf FTGFOP-1 First Flush Darjeeling. In fact, it would be quite a waste of money to buy a tea you don’t like.

In a way, buying tea that’s highly-graded on the pekoe system is like buying organic. What it really tells you is that you’re dealing with a legitimate tea producer that cares enough about their product to pick it right and have it graded by experts.

The World Tea Tasting Tour

Over the next couple of months, I will be taking you on a world tour of tea with a series of tastings and classes focused on teas from all around the world. The events will be at our tea bar on Fridays from 5:00 to 6:30. At each session, we’ll taste five to seven teas from a different country as we explore a bit of the country’s geography and tea culture. I will put a quick summary of each stop on the tour up here on the blog for those who can’t attend or who don’t remember which teas we covered.

The full tour consists of:

Friday, Feb 15 — All the Tea in China

Friday, Mar 1 — Tea. Earl Grey. Hot. (England)

Friday, Mar 8 — It’s Always Tea Time in India

Friday, Mar 15 — Japan: Bancha to Matcha (notes Part 1 and Part 2)

Friday, Mar 22 — Deepest Africa: The Tea of Kenya

Friday, Mar 29 — The Oolongs of Taiwan

Friday, Apr 5 — Rooibos from South Africa

Friday, Apr 12 — Yerba Maté from Argentina

Friday, Apr 26 — China part II: Pu-Erh

Friday, May 3 — India part II: Masala Chai

Each class will cost $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

There will be more information posted on Facebook before each event, including a list of the teas that we will taste in each event.

UPDATE MARCH 9: As I blog about each of these experiences, I’m going to create a link from this post to the post containing the outline and tasting notes. I’ve linked the first two.

UPDATE MARCH 23: I changed the dates of the last two events. There will not be a tasting on April 19.

Seasons of Tea

As my tea bar does more direct tea buying (as opposed to buying through distributors), I have an opportunity to taste some absolutely fascinating teas. As I tasted some estate-grown Darjeelings the other day, I was reminded of how much difference the picking time makes on the character of the tea.

The three teas on the right side of the picture above are all Darjeeling teas from the Glenburn estate. The terroir is identical. It’s the same varietal of Camellia sinensis var sinensis (the Chinese tea plant) — all FTGFOP1 clonals. They are all black teas. They were steeped for the same amount of time using the same water at the same temperature. I used the same amount of tea leaf for each cup. What’s the difference?

- The light golden tea second from left is a first-flush Darjeeling, picked on March 20th. At that time of year, the spring rains are over and the tea plants are covered with fresh young growth. The tea is very light in color, and the flavor is mild but complex with a touch of spiciness. Although all four of the teas in the picture were steeped 2-1/2 minutes, I actually prefer my first flush Darjeelings steeped for a considerably shorter time (although everyone has different opinions on that). I’m drinking a cup as I write this, and it’s just about right at a minute and a half.

- The amber cup to the right of the first-flush is a second-flush, picked in June. The drier summer climate produces a heartier cup of tea, with a flavor often described as “muscatel.” There is more body and a bit more astringency as well.

- The darkest cup of tea on the far right is called an Autumnal Darjeeling. This one was picked on November 10th. By then, the monsoons are over and the new growth on the tea plants has matured. An autumn-picked Darjeeling will be darker in color, stronger in flavor, and fuller-bodies, but without as much of the spicy notes Darjeelings are known for.

These seasonal differences account for massive differences in caffeine content as well. Early in the season, tea plants will have more caffeine concentrated in the new growth, which is what’s picked for the delicate high-end teas. The data that Kevin Gascoyne presented at World Tea Expo last year showed a 300% increase in caffeine between two pickings at different times of year in the same plantation.

Comparing Darjeeling teas can be difficult, as much of the “Darjeeling” tea on the market isn’t authentic. According to this 2007 article, the Darjeeling region produces 10,000 tonnes of tea per year, but 40,000 tonnes is sold around the world. Even if you don’t consider the local consumption, that means 3/4 of the tea sold as Darjeeling is grown somewhere else. That’s why it’s so important to buy from a trusted source.

When selecting teas, we tend to look first at the production style (black, green, white, oolong, pu-erh), and then for the origin (a Keemun black tea from China is quite different from an Assam black tea from India). As consumers, we rarely know the exact varietal of the plant or the picking season, but those factors are every bit as important to the final flavor.

I suppose the main message of this article is that you can’t judge a tea style on a single cup. You may love autumnal Darjeeling and dislike first-flush. You may enjoy a second flush from Risheehat and not the one from Singbulli.

Teas, Tisanes, and Terminology

Language evolves. I get that. Sometimes changes make communication easier, clearer, or shorter. Sometimes, however, the evolution of the meaning of a word does exactly the opposite. The subject of this blog is a good example.

The word “tea” refers to the tea plant (Camellia sinensis), the dried leaves of that plant, or the drink that is made by infusing those leaves in water.

The word “tisane” refers to any drink made by infusing leaves in water. Synonyms include “herbal tea” and “herbal infusion.”

Technically speaking, all teas are tisanes, but most tisanes are not teas.

In today’s culture, however, practically anything (except coffee and cocoa) that’s made by putting plant matter in water is called a tea. What’s my problem with that? It makes communication more difficult, less clear, and less terse.

- There is no other single word that means “a drink made with Camellia sinensis.” If we call everything tea, then we have to say “real tea” or “tea from the tea plant” or “Camellia sinensis tea” or something similarly ludicrous every time we want to refer specifically to tea rather than to all tisanes.

- There is a perfectly good word for “leaves infused in water.” There is no need to throw away “tisane” (or “herbal tea” or “infusion”) and replace it with a word that already has another meaning.

“But Gary,” I hear you cry, “people have been calling herbal infusions ‘tea’ for a long time!”

That’s true. I sometimes slip and call rooibos a tea myself. “Herbal infusion” is even an alternate definition of tea in the OED. I still maintain, however, that it makes clear, precise communication more difficult when trying to differentiate between tea (made from the Camellia sinensis plant) and drinks made from chamomile, honeybush, and willow bark.

Rooibos

Other words that go through this process are forced through it. Rooibos, for example, is the name for a specific tisane and the plant it’s made from (Aspalathus linearis). The word is Afrikaans for Red Bush. Despite the longtime use of the term in South Africa (the only place the rooibos plant grows), it was almost unknown in the United States in 1994 when Burke International of Texas registered “rooibos” as a trademark. This meant that in the United States, only Burke and its subsidiaries could use the common name of the plant. Had Burke not surrendered the trademark after starting to lose lawsuits, people would have been forced to come up with a new word.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t a decisive victory, as the South African Rooibos Council is being forced to repeat the process now with a French company.

As more people in the U.S. discover green rooibos, the name “red bush” becomes more confusing anyway. Rooibos, in my humble opinion, should remain the generic term here.

Oxidation vs. fermentation

There are other words in the tea industry that suffer from ambiguity and questionable correctness. You will find quite a bit of tea literature that refers to the oxidation of tea as fermentation. I had a bit of a row with Chris Kilham — The “Medicine Hunter” on Fox News — about this subject (it starts with “Coffee vs. Tea: Do your homework, Fox News” and continues with “Chris Kilham Responds“).

Fermentation and oxidation are closely related processes. That’s certainly true. But oxidation is the aerobic process that is used in the production of black and oolong tea, and fermentation is the anaerobic process that’s used in the production of pu-erh tea. Using the word “fermentation” to describe the processing of black tea may fit with a lot of (non-chemist) tea industry writers, but it makes it difficult to explain what real fermented tea is.

Precision matters

In chatting with friends, imprecise use of words doesn’t matter. If someone asks what kind of tea you want and you respond, “chamomile,” it’s perfectly clear what you want. But you’re an industry reporter, medical writer, or marketing copywriter, your job is to communicate unambiguously to your readers. Using the most correct terminology in the right way is a great way to do that.

Legend says that tea originated in China in 2737 B.C., over 100 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built. In this first stop on our

Legend says that tea originated in China in 2737 B.C., over 100 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built. In this first stop on our