Blog Archives

The Rooibos of South Africa: Stop 7 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

If you’re looking for a drink with all the health benefits of tea, a similarly great taste, but no caffeine, look to South Africa! Rooibos is made from the South African red bush (Aspalathus linearis). Using rooibos instead of tea is a great way to enjoy a caffeine-free hot (or iced) drink without using any chemical decaffeination process. Rooibos is full of antioxidants, Vitamins C and E, iron, zinc, potassium, and calcium. It is naturally sweet without adding sugar.

Rooibos grows only in the Western Cape of South Africa, and a similar plant called honeybush (the Cyclopia plant) grows in the Eastern Cape. Its flowers smell of honey, hence the name. The taste of honeybush is similar to rooibos, though perhaps a bit sweeter. Like rooibos, honeybush is naturally free of caffeine and tannins; perfect for a late-evening drink.

The teas we tasted were:

- Red rooibos (organic)

- Green rooibos (organic)

- Honeybush (organic)

- Jamaica red rooibos (organic, fair trade)

- Bluebeary relaxation (organic, fair trade)

- Iced rooibos

- Cape Town Fog (a vanilla rooibos latte!)

South Africa, as the name implies, sits at the very southern tip of the African continent. It completely surrounds a small country called Lesotho. South Africa covers 471,443 square miles (about three times the size of Montana) and has a population of 51,770,000 (a bit more than Spain). Despite wide open spaces in the middle of the country, the large cities make it overall densely populated.

The country has the largest economy in Africa, yet about 1/4 of the population is unemployed and living on the equivalent of US $1.25 per day.

Red rooibos

Rooibos isn’t a huge part of the South African economy. It does, however, employ about 5,000 people and generates a total annual revenue of around US $70 million, which is nothing to sneeze at. The plant is native to South Africa’s Western Cape, and the country produces about 24,000,000 pounds of rooibos per year.

The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans. In the U.S., it’s pronounced many different ways but most often some variant of ROY-boss or ROO-ee-bose.

I’ve written quite a bit about red rooibos in several posts — and about the copyright issues — so I won’t repeat it all here. Rooibos is also great as an ingredient in cooking: see my African Rooibos Hummus recipe for an example.

Green rooibos

Green rooibos isn’t oxidized, so it has a flavor profile closer to a green tea than a black tea. Again, I’ve written a lot about it, so I’ll just link to the old post.

Honeybush

Honeybush isn’t one single species of plant like rooibos. The name applies to a couple of dozen species of plants in the Cyclopia genus, of which four or five are used widely to make herbal teas. Honeybush grows primarily in Africa’s Eastern Cape, and isn’t nearly as well-known as rooibos.

It got its name from its honey-like aroma, but it also has a sweeter flavor than rooibos. It can be steeped a long time without bitterness, but I generally prefer about three minutes of steep time in boiling water.

Jamaica Red Rooibos

I decided to bring out a couple of flavored rooibos blends for the tasting as well. The first is Jamaica Red Rooibos, a Rishi blend. It has an extremely complex melange of flavors and aromas, and is not only a good drink, but fun to cook with as well (see my “Spicing up couscous” post).

Jamaica Red Rooibos is named for the Jamaica flower, a variety of hibiscus. The extensive ingredient list includes rooibos, hibiscus, schizandra berries, lemongrass, rosehips, licorice root, orange peel, passion fruit & mango flavor, essential orange, tangerine & clove oils

BlueBeary Relaxation

BlueBeary Relaxation one of the blends in our Yellowstone Wildlife Sanctuary fundraiser series (the spelling “BlueBeary” comes from the name of one of the bears at the Sanctuary). It’s an intensely blueberry experience that’s become a bedtime favorite of mine. It’s like drinking a blueberry muffin!

Iced rooibos

To make a really good cup of iced rooibos, prepare the hot infusion with about double the leaf you’d use normally, because pouring it over the ice will dilute it. Both green and red rooibos make great iced tea. I prefer both styles unadulterated, but many people drink iced red rooibos with sugar or honey.

Cape Town Fog

This South African take on the “London Fog” is a great caffeine-free latte. To prepare it, you’ll want to preheat the milk almost to boiling. If you have a frother of some kind, use it — aerating the milk improves the taste. Steep the red rooibos good and strong, and add a bit of vanilla syrup or extract. We use an aged vanilla extract for ours. Mix it all up, put a dab of foam on top if you frothed the milk, and optionally top with a light shake of cinnamon.

This was the seventh stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from February.

Cooking With Rooibos: African Rooibos Hummus

Last weekend, we hosted an “African Tea Experience” at the tea bar. Unlike our World Tea Tasting Tour sessions, this one was a private party that we donated to a local nonprofit organization for a silent auction fundraiser. Instead of just tasting some tea we made this a more immersive experience, including—among other things—food.

My first thought was to use the Hipster Hummus that we’ve prepared here before, but it’s really more of a Middle Eastern hummus than an African one. What’s the difference? I’m glad you asked.

Hummus is currently thought of as a Middle Eastern dish. Lebanon is pushing the European Commission to declare hummus a uniquely Lebanese food. In Israel, hummus is a staple. You can find it anywhere in Turkey or Palestine. But that’s not where the dish originated.

According to Gil Marks’ Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, the earliest known recipes for hummus date back to 13th century cookbooks from Cairo. It’s still a popular dish throughout northern Africa, and there are few differences between the African version and the Middle Eastern version. For this event, I decided to make a more Africanized version of our regular hummus.

All hummus is based on chickpeas (or garbanzo beans) and tahini (sesame paste). The primary ingredient difference in the African version is cumin. I decided to add red rooibos, which is a uniquely South African tisane (it’s often called “tea,” but since it isn’t made from Camellia sinensis, it isn’t technically tea). What we ended up with isn’t traditional, but it did get rave reviews. Despite the hot sauce, it isn’t overly spicy. Personally, I’d consider it almost mild. You could substitute a hot paprika for the milder roasted one that I used to give it more kick, or increase the Sriracha sauce.

Ingredients

- One 15-oz can garbanzo beans/chickpeas

- 1-1/2 tbsp sesame tahini paste

- 1 tsp cumin

- 1/2 ounce red rooibos leaves

- 1-1/2 tsp minced garlic

- 4 tbsp fresh-squeezed orange juice

- 1/2 tsp sea salt

- 1/2 tbps Sriracha

- 1/4 tsp roasted Israeli paprika

- 1 tsp olive oil

- sprig of fresh parsley

Process

- Drain the garbanzo beans/chickpeas and set aside the juice

- Heat the juice almost to boiling and add the rooibos — steep for five minutes

- Put beans, tahini, garlic, cumin, orange juice, salt, and Sriracha in a food processor

- Add 1/4 cup of the tea infusion to the food processor

- Blend everything to a smooth consistency

- Chill overnight in the fridge

- Spread hummus on plate with a dip in the center

- Drizzle olive oil through the center dip (not shown in the picture above, where I put pita chips in the middle instead)

- Sprinkle the paprika over the hummus, and garnish with parsley

- Serve with pita chips or fresh pita bread

The flavor of the rooibos definitely comes through, although it’s a bit subtle. Feel free to increase both the amount of leaf and the steeping time if you want more rooibos character.

Enjoy!

Teas, Tisanes, and Terminology

Language evolves. I get that. Sometimes changes make communication easier, clearer, or shorter. Sometimes, however, the evolution of the meaning of a word does exactly the opposite. The subject of this blog is a good example.

The word “tea” refers to the tea plant (Camellia sinensis), the dried leaves of that plant, or the drink that is made by infusing those leaves in water.

The word “tisane” refers to any drink made by infusing leaves in water. Synonyms include “herbal tea” and “herbal infusion.”

Technically speaking, all teas are tisanes, but most tisanes are not teas.

In today’s culture, however, practically anything (except coffee and cocoa) that’s made by putting plant matter in water is called a tea. What’s my problem with that? It makes communication more difficult, less clear, and less terse.

- There is no other single word that means “a drink made with Camellia sinensis.” If we call everything tea, then we have to say “real tea” or “tea from the tea plant” or “Camellia sinensis tea” or something similarly ludicrous every time we want to refer specifically to tea rather than to all tisanes.

- There is a perfectly good word for “leaves infused in water.” There is no need to throw away “tisane” (or “herbal tea” or “infusion”) and replace it with a word that already has another meaning.

“But Gary,” I hear you cry, “people have been calling herbal infusions ‘tea’ for a long time!”

That’s true. I sometimes slip and call rooibos a tea myself. “Herbal infusion” is even an alternate definition of tea in the OED. I still maintain, however, that it makes clear, precise communication more difficult when trying to differentiate between tea (made from the Camellia sinensis plant) and drinks made from chamomile, honeybush, and willow bark.

Rooibos

Other words that go through this process are forced through it. Rooibos, for example, is the name for a specific tisane and the plant it’s made from (Aspalathus linearis). The word is Afrikaans for Red Bush. Despite the longtime use of the term in South Africa (the only place the rooibos plant grows), it was almost unknown in the United States in 1994 when Burke International of Texas registered “rooibos” as a trademark. This meant that in the United States, only Burke and its subsidiaries could use the common name of the plant. Had Burke not surrendered the trademark after starting to lose lawsuits, people would have been forced to come up with a new word.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t a decisive victory, as the South African Rooibos Council is being forced to repeat the process now with a French company.

As more people in the U.S. discover green rooibos, the name “red bush” becomes more confusing anyway. Rooibos, in my humble opinion, should remain the generic term here.

Oxidation vs. fermentation

There are other words in the tea industry that suffer from ambiguity and questionable correctness. You will find quite a bit of tea literature that refers to the oxidation of tea as fermentation. I had a bit of a row with Chris Kilham — The “Medicine Hunter” on Fox News — about this subject (it starts with “Coffee vs. Tea: Do your homework, Fox News” and continues with “Chris Kilham Responds“).

Fermentation and oxidation are closely related processes. That’s certainly true. But oxidation is the aerobic process that is used in the production of black and oolong tea, and fermentation is the anaerobic process that’s used in the production of pu-erh tea. Using the word “fermentation” to describe the processing of black tea may fit with a lot of (non-chemist) tea industry writers, but it makes it difficult to explain what real fermented tea is.

Precision matters

In chatting with friends, imprecise use of words doesn’t matter. If someone asks what kind of tea you want and you respond, “chamomile,” it’s perfectly clear what you want. But you’re an industry reporter, medical writer, or marketing copywriter, your job is to communicate unambiguously to your readers. Using the most correct terminology in the right way is a great way to do that.

Rooibos: The African Red Bush

How have I been at this blog for so long without writing about rooibos? Oh, I know this blog is about tea, and I did write a post about green rooibos last year, but I haven’t covered straight red rooibos yet.

Rooibos comes from a bush called Aspalathus linearis, which grows in the west cape of South Africa. The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans.

Rooibos is also often called “red tea,” but most tea professionals shy away from that name for several reasons:

- The term “red tea” is used by the Chinese to refer to what we call “black tea.” No sense having two different drinks with the same name.

- Rooibos isn’t tea, since it doesn’t come from the Camellia sinensis plant. Instead, it is a tisane or herbal infusion.

- Rooibos only has that rich red color when it’s processed like a black tea. Green rooibos is more of a golden honey-colored infusion.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Unlike “real” tea, which all has caffeine, rooibos is naturally caffeine-free. Since the flavor is similar to a mild black tea, this makes it a favorite bedtime beverage for many tea drinkers. Rooibos is also high in antioxidants.

Herbalists make many claims about the health properties of the rooibos tisanes. The Web site for the South African Rooibos Council (SARC), in fact, has very little information that isn’t in some way tied back to health claims. There are more and more studies being done, but available data are lacking in specifics (in my opinion, anyway) so I’m not going to quote any of those there. Feel free to check SARC’s site for lots of studies.

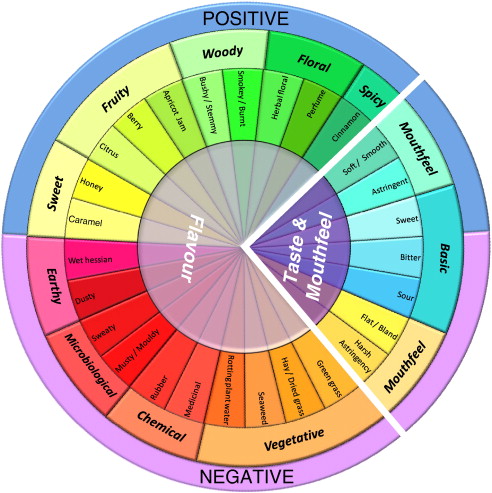

I don’t mean to imply that rooibos is only about the health benefits. It is, in fact, a very tasty drink. Most rooibos drinkers in the U.S. enjoy it straight or with a bit of sweetener (honey or sugar). In South Africa, it is commonly served with a bit of milk or lemon as well as honey. A group funded by SARC and Stellenbosch University has recently developed a “sensory wheel” for rooibos, describing both the desirable and undesirable aspects of flavor and mouthfeel. If you are interested in more information, click on the wheel below.

Rooibos Sensory Wheel as described in the article “Sensory characterization of rooibos tea and the development of a rooibos sensory wheel and lexicon,” available on Science Direct. Click the wheel above to view the article — there is a charge for the full text version.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Compared to tea, rooibos is a pretty small market. South Africa’s annual rooibos production is about 12,000 tons. That output is about equivalent to annual tea production of the Darjeeling region of India, or about a tenth of the tea production of Japan (the 8th largest tea producing country). Nonetheless, rooibos is important to South Africa, employing about 5,000 people and generating about $70 million in revenues.

The leaves of the rooibos bush are more like needles than the broad leaves of a tea plant. To produce red rooibos, the leaves are harvested, crushed, and oxidized using a process based on the one used in making Chinese black tea. Typically, the leaves are sprayed with water and allowed to oxidize for about 12 hours before being spread out in the sun to dry.

Green rooibos, as the name implies, is unoxidized or very lightly oxidized, and is processed more like a green tea.

For more information about the rooibos industry, I recommend the article Disputing a Name, Developing a Geographical Indication, from the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Tea and caffeine part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

This article is the second of a three-part series.

Part I: What is caffeine?

Part II: Exploding the myths

Part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

So you’ve decided you like tea, but you really don’t want (or can’t have) the caffeine. What are your alternatives?

Well, first there’s decaf tea. As Part I of this series explained, decaffeination processes don’t remove 100% of the caffeine, so this is a reasonable alternative if you want less caffeine, but not if you want none at all. There’s another problem with switching to decaf: the selection of high-quality decaffeinated tea is — let’s just say, limited.

It’s easy to find a decaf Earl Grey or a decaf version of your basic Lipton-in-a-bag. But if your tastes run more to sheng pu-erh, sencha, dragonwell, lapsang souchong, silver needle, Iron Goddess of Mercy, or organic first-flush Darjeeling, you have a problem.

You can try the “wash” home-decaffeination method, but I explained a couple of days ago why that process is overrated. You’re likely to be able to remove 20% or so of the caffeine that way, but that’s about it.

Another alternative is simply to brew weaker tea and/or use more infusions. Let’s do the math for an example. Assume you’re a big fan of an oolong that contains 80 mg of caffeine in a tablespoon of leaves, and you drink four cups of tea per day.

If you use a fresh tablespoon of leaves for each cup, and you steep it for three minutes, you will be extracting about 42% of the caffeine in each cup, which equals 34 mg per cup, or a total of 136 mg of caffeine for the day. If you shorten your steep time to two minutes, the extraction level drops to about 33% (total of 106 mg). Alternatively, you could use the leaves twice each time, so you’re extracting about 63% of the caffeine, but using a total of half as many leaves (total of 101 mg). Or, if you don’t mind significantly weaker tea, just use 1-1/2 teaspoons of leaves instead of a full tablespoon. Half the leaves means half the caffeine (total of 68 mg).

No caffeine at all

If you look through the selection of teas in a health-food store, you’ll notice that most of them have no tea at all, and the vast majority of those non-tea drinks have no caffeine. The problem is that chamomile for a tea drinker is like Scotch to a wine drinker; it’s just not the same.

There are a couple of beverages, however, that are somewhat similar to tea. Both come from South Africa and both are naturally caffeine-free.

Rooibos is often called “red bush” in the United States because the way it’s usually prepared leaves a deep red infusion. Typically, rooibos is oxidized (not fermented) like a black tea. It can also be prepared more like a green tea. I blogged about green rooibos last August if you’d like to know more about it.

North American news shows, along with people like Oprah and Dr. Oz, have been singing the praises of rooibos lately, bringing it more into the mainstream awareness. It is very high in antioxidants and much lower in tannins than a black tea. Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of independent research published about it yet, so many of the claims can’t really be backed up. The one that can be backed is that it has no caffeine and it tastes kind of like black tea (green rooibos is a bit grassy with malty undertones, more like a Japanese steamed green tea with a touch of black Assam).

Honeybush, like rooibos, grows only in South Africa. Also like rooibos, it is naturally caffeine-free and can be prepared either as a red or a green “tea.” When blooming, the flowers smell like honey, and honeybush tends to be somewhat sweeter than rooibos. Honeybush isn’t nearly as well-known as rooibos in the U.S., and the green version is very hard to find. I’ve found that if you want a flavored honeybush, citrus complements it very well. My “Hammer & Cremesickle Red” is the most popular honeybush blend in our tea bar (here is a blog post about it, and you can find it on the store website here).

A blended approach

If you like the idea of reducing your caffeine intake, but you don’t like the idea of a weaker tea (as I described above) or switching to rooibos or honeybush, you might want to consider blending. If you mix your tea half-and-half with something containing no caffeine, then you can still brew a strong drink, but get only half the caffeine from it. Combine that with the other tricks, like taking two infusions, and you can cut it even farther.

Tea and caffeine part I: What is caffeine?

The most popular drug?

This article is the first of a three-part series.

Part I: What is caffeine?

Part II: Exploding the myths

Part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

In his excellent book, A History of the World in 6 Glasses, Tom Standage selected the six beverages that he felt had the greatest influence on the development of human civilization. Three of the six contain alcohol; three contain caffeine. Tea was one of the six.

Is it the caffeine that has made tea one of the most popular beverages in the world? The flavor? Its relaxing effects? I think that without caffeine, Camellia sinensis would be just another of the hundreds of plant species that taste good when you make an infusion or tisane out of it. Perhaps yerba maté would be the drink that challenged coffee for supremacy in the non-alcoholic beverage world.

“Caffeine is the world’s most popular drug”

The above quote opens a paper entitled Caffeine Content of Brewed Teas (PDF version here) by Jenna Chin and four others from the University of Florida College of Medicine. I’ll be citing that paper again in Part II of this series. Richard Lovett, in a 2005 New Scientist article, said that 90% of adults in North America consume caffeine on a daily basis.

But yes, caffeine is a drug. It is known as a stimulant, but its effects are more varied (and sometimes more subtle) than that. It can reduce fatigue, increase focus, speed up though processes, and increase coordination. It can also interact with other xanthines to produce different effects in different drinks, which is one reason coffee, tea, and chocolate all affect us differently.

Tea, for example, contains a compound called L-theanine, which can smooth out the “spike & crash” effect of caffeine in coffee and increase the caffeine’s effect on alertness. In other words, with L-theanine present, less caffeine can have a greater effect. See a great article from RateTea about L-theanine here.

Even though Part II of this series is the one that dispels myths, I really need to address a common misconception right now. First, I’m going to make sure to define my terms: for purposes of this series, “tea” refers to beverages made from the Camellia sinensis plant (the tea bush) only. I’ll refer to all other infused-leaf products as “tisanes.” Okay, now that we have that out of the way:

“All tea contains caffeine”

Yes, I said ALL tea. The study I mentioned a couple of paragraphs ago measured and compared the caffeine content of fifteen regular black, white, and green teas with three “decaffeinated” teas and two herbal teas (tisanes). With a five-minute steep time, the regular teas ranged from 25 to 61 mg of caffeine per six-ounce cups. The decaf teas ranged from 1.8 to 10 mg per six ounce cup.

That’s right. The lowest caffeine “regular” tea they tested (Twinings English Breakfast) had only 2-1/2 times the caffeine of the most potent “decaffeinated” tea (Stash Premium Green Decaf).

There are two popular ways to remove caffeine from tea. In one, the so-called “direct method,” the leaves are steamed and then rinsed in a solvent (either dichloromethane or ethyl acetate). Then they drain off the solvent and re-steam the leaves to make sure to rinse away any leftover solvent. The other process, known as the CO2 method, involves rinsing the leaves with liquid carbon dioxide at very high pressure. Both of these methods leave behind some residual caffeine.

(As a side note: I’m not a fan of either process. When I don’t want caffeine, I’d much rather drink rooibos than a decaf tea. I only have one decaf tea out of over 80 teas and 20 tisanes at my tea bar, and I’m discontinuing that one.)

This is why tea professionals need to make a strong distinction between the terms “decaffeinated” (tea that has had most of its caffeine removed) and “naturally caffeine-free” (tisanes that naturally contain no caffeine such as rooibos, honeybush, and chamomile).

“Coffee has more caffeine than tea”

Almost everyone will agree with the statement. For the most part, it is true, assuming you add some qualifiers: The average cup of fresh-brewed loose-leaf tea contains less than half the caffeine of the average cup of fresh-brewed coffee. In the seminar, Tea, Nutrition, and Health: Myths and Truths for the Layman, at World Tea Expo 2012, the studies Kyle Stewart and Neva Cochran quoted showed the plain cup of fresh-brewed coffee at 17 mg of caffeine per ounce versus the plain cup of fresh-brewed tea at 7 mg per ounce (that’s 42 mg per six-ounce cup, which agrees nicely with the numbers from the caffeine content study I quoted above).

Interestingly, though, a pound of tea leaves contains more caffeine than a pound of coffee beans. How can that be? Because you use more coffee (by weight) than tea to make a single cup, and caffeine is extracted more efficiently from ground-up beans than from chunks of tea leaf. Tea is usually not brewed as strong as coffee, either.

At another 2012 World Tea Expo seminar, A Step Toward Caffeine and Antioxidant Clarity, Kevin Gascoyne presented research he had done comparing caffeine levels in dozens of different teas (plus a tisane or two). The difference between Kevin’s work and every other study I’ve seen is that he prepared each tea as people would actually drink it. For example, the Bai Mu Dan white tea was steeped 6 minutes in 176-degree water, while the Tie Guan Yin (Iron Goddess of Mercy) oolong was steeped 1.5 minutes in 203-degree water. Matcha powder was not steeped per se, but stirred into the water and tested without filtering.

The results? Caffeine content ranged from 12mg to 58mg for the leaf teas, and 126mg for the matcha — which is higher than some coffees.

In our next installment, I’ll look at the myths regarding caffeine in tea, including what kinds of tea have the most caffeine and how you can remove the caffeine at home all by yourself — or can you?

Lady Grey

Today was tea blending day at the tea bar, as I mixed up new batches of our house blends. As I was working on our Lady Grey, I got to thinking about how incredibly different Lady Grey teas are from one company to the next, and decided to do a bit of reading on the subject.

Today was tea blending day at the tea bar, as I mixed up new batches of our house blends. As I was working on our Lady Grey, I got to thinking about how incredibly different Lady Grey teas are from one company to the next, and decided to do a bit of reading on the subject.

It didn’t take long to find a comment that “Lady Grey” is a registered trademark of R. Twining and Company in the U.S. and U.K. (here’s a link to the trademark search on Trademarkia that shows it renewed in March of 2006). This hasn’t stopped quite a few companies from producing their own variations, like Jasmine Pearl (theirs has orange zest and lemon myrtle, but no bergamot!), SereneTeaz (an Earl Grey with lavender), American Tea Room (they don’t have a full ingredient list, but it includes cornflower petals), and Tea Embassy (another Earl Grey with lavender).

Should I follow their lead and continue calling my blend Lady Grey? Nah. I have better things to do with my time and money than fight legal battles. I’ll do the right thing and follow the example of Marks & Spencer (they call theirs Empress Grey) and Trader Joe’s (Duchess Grey).

Twinings originally named their Lady Grey tea for Mary Elizabeth Grey. Their Earl Grey tea (which they changed last year) was named for her husband, Charles, who was the second Earl Grey. Twinings uses less bergamot in their Lady Grey than they do in Earl Grey, but they add other citrus and some cornflower.

I’ve never understood the rationale of “clone blends.” My “Lady Grey” isn’t the same as anyone else’s. If it was, I’d just buy theirs. I want something different. Mine is an organic blend, using Chinese black tea, oil of bergamot, wild Tibetan lavender, a little bit of vanilla, and a touch of rooibos.

What to call it? The one consistent thing about all of our other Earl Grey teas is the word “Earl.” Earl Green (green tea + bergamot), Earl Red (rooibos + bergamot), and all of the blends that use the full “Earl Grey” moniker, like Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey and Cream Earl Grey. The name “Lady Grey” keeps the “Grey” instead of the “Earl,” but is still connected.

So I have done what I often do in such situations: turn the question over to my friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. I’ve asked Facebook and the Twitterverse for suggestions, and I’m starting a thread on my favorite message board (the Straight Dope). When we decide on a new name, you’ll read about it here first!

Orange Spice Carrot Cake Muffins

As promised, here’s the second recipe from our recent Chamber of Commerce party. Our food theme was cooking with tea, and this was a variant of a recipe that Bigelow Tea originally published. Obviously, we substituted teas that we sell at our Tea Bar for what they originally suggested.

As promised, here’s the second recipe from our recent Chamber of Commerce party. Our food theme was cooking with tea, and this was a variant of a recipe that Bigelow Tea originally published. Obviously, we substituted teas that we sell at our Tea Bar for what they originally suggested.

In the muffins themselves, Kathy used our Cinnamon Orange Spice Ceylon tea, which adds some nice black tea flavor to the pure herbal blend in the original recipe.

For the frosting, she used one of my house blends: Hammer & Cremesickle Red Tea (you can order it here). The honeybush, rooibos, orange, and vanilla give it a sweet, rich, creamy flavor.

We made mini muffins, since they were being served hors d’oeuvre style. Feel free to try this as full-sized muffins or even a cake tin. Just adjust the baking time a bit.

Muffin Ingredients

- 1/2 ounce of Cinnamon Orange Spice Ceylon Tea

- 1/2 cup water

- 1-3/4 cup sugar

- 3/4 cup vegetable oil

- 3 large eggs

- 1 can of mandarin oranges

- 2 tsp vanilla extract

- 2 tsp fresh-grated orange zest

- 2-1/2 cups all-purpose flour

- 2-1/2 tsp baking soda

- 2 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 2 cups shredded carrots

Muffin Process

- Boil water and add to tea. Steep for 6 minutes and strain out leaves.

- Heat oven to 350 F.

- In a large mixing bowl, combine sugar, eggs, and vegetable oil. Mix thoroughly at high speed for 1 to 2 minutes, or until thick and creamy.

- Drain the can of mandarin oranges (discard the liquid), and add it to the mixing bowl, along with the tea, vanilla, and orange zest. Continue mixing until well blended.

- In a separate bowl, stir together the flour, baking soda, salt, and cinnamon. Add this blend to the mixing bowl and mix at low speed for another 1-2 minutes.

- Add the shredded carrots and continue mixing until well blended.

- Scoop the batter into muffin tins, either using paper muffin cups or spraying the tins with non-stick spray. Fill a bit over 1/2 full.

- Bake for 18 to 20 minutes or until a wooden toothpick inserted in the center of a muffin comes out clean.

Frosting Ingredients

- 1/4 ounce Hammer & Cremesickle Red Tea

- 1/4 cup water

- 1 eight-ounce package of cream cheese

- 1 tbsp butter (softened)

- 3-1/2 cups confectioner’s sugar

Frosting Process

- Boil water and add to tea. Steep for 6 minutes and strain out leaves.

- Combine butter and cream cheese in a mixing bowl. Mix at high speed for one minute or until light and creamy.

- Add 2 tbsp of tea from step 1 and mix well.

- Add confectioner’s sugar and mix thoroughly for 1 to 2 minutes or until smooth and creamy.

- After the muffins have cooled, frost the top of each one with frosting.

These were a smash hit at the party, along with the Hipster Hummus recipe that I posted last week, and a couple more that I’ll be posting soon (next in the series: Meatballs in Lapsang Souchong Cream Sauce).

Spicing up couscous

Jamaica Red Rooibos, courtesy of Rishi Tea

I have played around quite a bit with tea as a flavoring for vegetables, rice, fish, and other dishes. A few months ago, I was trying to decide on a good tea combo for adding some extra flavor to couscous. Most of the time, I use actual tea (made from the Camellia sinensis plant). Late one evening, however, when I was enjoying a cup of rooibos — a.k.a. African red bush — it occurred to me that it might make a great ingredient as well.

Straight rooibos wasn’t quite the flavor I was looking for, but one of the more popular blends at our tea bar seemed like just the ticket: Jamaica Red Rooibos from Rishi Tea.

The tea is named for the Jamaica flower, which is one of the nicknames for a variety of hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa) commonly used in tea. Rishi’s blend is complex. In addition to the rooibos and hibiscus flowers, it also contains lemongrass, schizandra berries, rosehips, licorice root, orange peel, passion fruit flavor, essential oils of orange and tangerine, mango flavor, and essential clove oil.

After a bit of monkeying around, I settled on a very simple recipe:

- Following the instructions with your particular couscous, bring enough water for four servings to a boil, and remove from heat.

- Add 2-3 tablespoons of Jamaica Red Rooibos and steep for seven minutes.

- Remove the leaves. I used a disposable tea filter. You could just as easily dump the leaves in the water and pour through a strainer.

- Bring the water back to a boil and add the couscous.

- Continue as you would for unflavored couscous.

For a little bit of extra texture, try adding a few tablespoons of chopped walnuts.

You can buy this tea from a variety of sources, including (of course) our own tea bar.

UPDATE May 2012: The Tea Bar’s website is now up and running, and you can order Jamaica Red Rooibos here.

Hammer & Cremesickle Red

Isn’t it fun how names develop for tea blends? The naming process is almost as much fun as the blending process itself.

Isn’t it fun how names develop for tea blends? The naming process is almost as much fun as the blending process itself.

For weeks, I had been trying to come up with a tea that invoked the taste of the creamsicles I used to enjoy so much as a kid (Who am I kidding? I still enjoy them!). Frozen orange over a vanilla bar. Yum! My initial attempts were based on black teas, and the flavor of the tea kept overwhelming the flavor of the orange and vanilla.

Finally, I hit on something that seemed to work. A blend of rooibos and honeybush as a base, which adds a rich, creamy texture. Orange and natural vanilla for the cremesicle flavor, and just a touch of carob to round everything out. I tried it both hot and iced and decided I liked it.

Some friends, Al and Ranetta, popped by the tea bar, and I asked if they’d like to sample my newest concoction. Being willing guinea pigs, they acquiesced. They tasted, we talked, and they liked it. Ranetta asked if she could buy a few ounces. As I started to write out the label, my hand stopped, poised to write, as I realized I hadn’t named the new blend yet.

I decided to write “orange creamsicle,” but Al was talking and distracting me (It’s all Al’s fault. Really it is). I misspelled the word. Unbelievable, isn’t it? But I threw an extra K in there. I noticed the error and commented on it.

“How did you spell it?” Al asked.

“Sickle with a K,” I replied. “As in ‘hammer and sickle’.”

It struck us both at about the same time that this is a red tea (the rooibos plant is also called the African redbush), so that could end up as a very fitting name. Al asked for a sheet of paper and set to work sketching a logo. I scanned, tweaked, and colorized his masterpiece (sorry, Al) and included it at the top of this blog post.

(Please imagine, in the following paragraph, that I’m speaking with the same accent as Mickey Rourke used when playing Whiplash in the second Iron Man movie. If you can’t do that, I’ll settle for Boris Badenov from the Rocky & Bullwinkle show.)

You must buy Hammer & Creamsickle Red now, comrade. Will take you back to childhood summers at family dacha on Volga river. Decadent treat from American capitalists. We have our own capitalism now; our own pravda. We have no money, but tea is cheap. Try now.

[UPDATE Feb 2012: We used this tea in the frosting for our Orange Spice Carrot Cake Muffins. It worked beautifully!]

[UPDATE Apr 2012: Al has drawn us another logo, this time for Robson’s Honey Mint Tea. He does great work.]

[UPDATE May 2012: Hammer & Cremesickle Red Tea is now available on our new Tea Bar website. I’ve updated the links in this article accordingly.]