Blog Archives

An open letter to restaurants about tea

NOTE: I originally wrote this in 2014. Not much has changed since then, but since it’s been ten years, I decided it could use an update, so here’s the new & improved version.

Dear Restaurants,

I love you. Really I do. I’m not a picky guy. I’m certainly not a snob. I love a five-course meal at a five-star restaurant, but I also must confess a fondness for a “Snag Burger” at the bar down the street from my shop. I love a good Indian buffet, a medium-rare steak, authentic London fish and chips, and an authentic Inverness haggis with neeps & tatties. Basically, if the chef cares about how the food tastes, I’m probably going to enjoy it. And if your servers care about serving the customers, I’m probably going to enjoy being in your restaurant. I love eating out.

But we’ve really got to talk about your tea.

To many people, having the right wine to go with their dinner transforms a good meal into a great one. Coffee drinkers will greatly appreciate fresh-brewed coffee, and beer aficionados will be greatly disappointed it you offer nothing but bland “megabrews” like Bud and Coors.

Those of us that love our tea feel exactly the same way. I’ve had some wonderful meals in restaurants and gone home disappointed because I got some bitter, oversteeped Lipton tea from a teabag instead of the restaurant putting in just a wee bit of effort and providing a good cup.

I’m not a tea Nazi, telling you and your other patrons the one and only way to make a proper cup of tea. Most of what I’m asking for is a proper selection and giving us the option to steep it as we wish.

#1: Tell us (or show us) the options!

First, if your restaurant is even half a notch above fast food, you have more than one type of tea, right? It may be powdered sweepings from the factory floor in a Lipton teabag, but you’ll have a black tea, a green tea, something without caffeine, and either Earl Grey or Moroccan Mint. If you don’t offer at least those four, you’d might as well hang a sign that says, “Tea Drinkers Not Welcome.”

So let’s start with that. When we order a cup of hot tea, either ask what kind we want, or present us with a basket or box containing a selection to choose from. Don’t just bring out a cup of black tea and then let us find out later that you had other options.

#2: Hot water. Really hot water.

Next, don’t grab the water until you’re on the way to the table. If we’re ordering black tea (and that includes Earl Grey), then we want that water boiling, or darned close to it

If we’re drinking tea that requires cooler water, such as a green or white tea, then we’d really prefer to get the boiling water and let it cool down ourselves. You can always cool water that’s too hot just by waiting, but you can’t heat water that’s too cold when you’re sitting at a table in a restaurant.

And now, a big no-no. Don’t ever ever put the tea leaves (or tea bag) in the water before you bring it to us (see below). The only exception to this rule is if you run a tea shop and your waitstaff plans to monitor the entire steeping process for us, in which case you’ll be controlling the steep time as well.

#3: The tea meets the water at the table.

There are several reasons for this.

First, most serious tea drinkers have their own opinions on how long their tea should be steeped. I typically short-steep my black teas and drink them straight. My friend Angela steeps hers long and strong and adds milk. There’s no way to prepare a cup of tea that will make both of us happy. You have to let us do it ourselves.

That said, if you start the tea steeping in the kitchen, we have no idea how long the leaves have been in the water when it gets to our table. A glass carafe helps that, but if we don’t know the particular brand and style of tea you’re serving, it’s really hard to judge by the color.

Additionally, not all tea takes the same water temperature. If I’m drinking black tea, I’ll pour in that boiling water the second it gets to me. If I’m drinking green or white tea, I’m going to let the water cool a bit first. Boiling water makes green tea bitter.

#4: Give us something to do with used leaves or teabags.

Once our tea is steeped to our liking, we’re going to want to remove the leaves from the water or pour the water off of the leaves.

I’ve been in many restaurants that give me a cup of water and a teabag, but no saucer to put the bag on when I’m done steeping it. I really don’t want a soggy teabag on my dinner plate, and you probably don’t want it on the tablecloth or place mat. Even the nice places that bring me a pot of water with a strainer full of leaves and a cozy to keep the pot warm sometimes don’t provide a place to put that strainer. Oh, and this reminds me of rule five:

#5: Don’t just dump leaves loose in a pot with a spout strainer unless it’s a single-serving pot.

It’s frustrating to pour off a cup of tea and know that by the time I’m ready for the second cup, it will be oversteeped and nasty and there’s not a thing I can do about it.

#6: Don’t add anything to the tea.

It’s fine to ask if we want sweetener or milk or lemon, but for goodness sake don’t add it without asking. We’re all different, but for me and a lot of other Americans, serving me a cup of good tea with milk in it is like serving me a good steak with ketchup on it. See the theme here? Give us options instead of deciding for us.

#7: If you serve iced tea, brew it.

Iced tea is incredibly easy to make fresh (sweet tea can be another issue), so please don’t use the powdered stuff! Just brew a pitcher of tea, pour it over ice, and voilà! Real iced tea. And please, oh please, don’t pre-sweeten it or throw a lemon slice in it. Give us some sweetener options and serve the lemon on the side.

Those seven rules will cover the basics. All but the real tea snobs can make something acceptable to drink if you have a few choices (which need to include unflavored options—don’t give us only Earl Grey, mint, fruity stuff, and herbal stuff) and serve it properly. But if you’d like to upgrade the experience and really make us tea drinkers feel welcome, here are a few bonus tips:

BONUS TIP #1: Loose-leaf tea makes a big difference to tea afficionados.

I know it’s a lot more work having to scoop a spoonful of leaves into an infuser than it is to toss a teabag in a cup. I get that. But to a tea drinker, it matters. It’s like getting fresh sliced peaches instead of peaches from a can, or fresh-baked bread instead of a slice from the grocery store.

BONUS TIP #2: Make sure all of your servers can answer rudimentary questions about your tea selection.

Everyone who works there should know which of your teas have caffeine and which don’t. They should know the difference between green and black tea (and know that Moroccan Mint is green and Earl Grey is black). They should know the teas from the tisanes (herbals), and they should know which ones are organic and/or fair trade.

If you serve loose-leaf tea, as opposed to bagged dust, give the staff a bit more information, like origin and style. You want your server to be able to tell a customer whether that red wine is a Merlot or Zinfandel and whether it’s from Bordeaux or Napa Valley. Why shouldn’t they be able to say whether the black tea is a Darjeeling, a Ceylon, or a Keemun?

BONUS TIP #3: Give us a couple of upgraded options.

Offering a oolong, a white tea, or a pu-erh makes me feel like you really want me to enjoy the experience. I don’t even mind paying more for a Bai Hao or a Silver Needle. It’s like offering some really nice wines in addition to the everyday wines; or offering craft beer in addition to Bud Light. That tea can make a good meal a really memorable one.

Attitude is everything in the service industry. If you and your staff are proud of the food you serve, it shows. Steak lovers look for restaurants that take pride in their steaks. Tea lovers look for restaurants that take pride in their tea. Most of the time, we’re lucky to find a restaurant that will even put a bit of effort into their tea, much less take pride in it.

If you aren’t a tea expert, find one and ask for advice. Show that you’re trying, and that you take as much pride in your drinks as you do in your food. We will notice. You will turn us into regular customers. We’ll be happy and you’ll be happy. We all win.

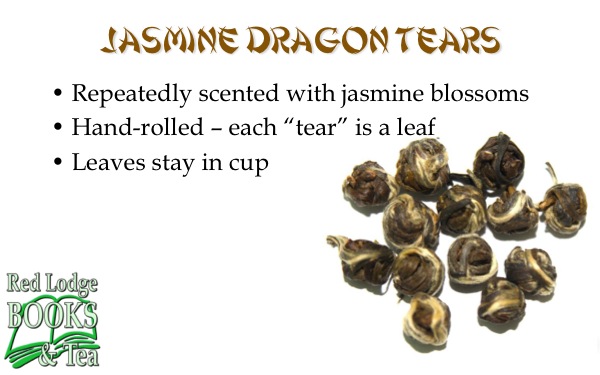

While writing this, I was drinking Jasmine King, a jasmine silver needle white tea. The touch of woodiness in the tea blended beautifully with the heavenly aroma of the jasmine. I don’t drink a lot of white tea, but I’m getting hooked on this one.

Yerba mate

Let’s get this out of the way first: is it spelled yerba mate or maté? Normally, when words from other languages are adopted into English, their accent marks go away. In this case, it’s the other way around. In both Spanish and Portuguese, the word is spelled mate and pronounced MAH-tay. No accent mark is used, because it would shift the emphasis to the 2nd syllable. The word maté in Spanish means “killed.”

In the United States, people unfamiliar with the drink see “yerba mate” written on a jar in a tea shop and pronounce mate to rhyme with late. So it has become accepted in English to add the accent above the e just to help us pronounce the word right. Linguists call this a hypercorrection.

Yerba, on the other hand, is spelled consistently in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, but the pronunciation varies depending on where you are. As you move across South America, it shifts from YER-ba to JHER-ba.

Directly translated, a mate is a gourd, and yerba is an herb, so yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) is literally the herb you drink from a gourd. I don’t really care which way you spell (or pronounce) the word as long as you give this delicious drink a try!

Yerba mate is a species of holly that contains caffeine (not, as previously thought, some related molecule called mateine). It grows in Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, and is the caffeinated beverage of choice for many people who live in those countries.

In the U.S., mate is usually made like tea, with the leaves steeped in boiling water for a few minutes and then removed. This, however, isn’t the way Argentinian gauchos (cowboys) been drinking mate in South America for centuries.

The process uses four elements: dried yerba mate leaves, hot water, a gourd (mate), and a bombilla (straw). Bombilla is another word that varies in pronunciation in different parts of South America, ranging from BOM-bee-ya to BOM-beezh-a.

Drinking mate was a social time for the gauchos and still is throughout much of South America. You generally won’t find yerba mate served this way in a U.S. tea shop, because it’s darned near impossible to clean a natural gourd to health department standards.

- First, the host (known as the cebador), fills the gourd about 1/2 to 2/3 full of leaf. Yeah, that’s a lot of leaf, but we’ll get a lot of cups out of it!

- Next, the cebador shakes or taps the gourd at an angle to get the fine particles to settle to the bottom and the stems and large pieces to rise to the top, making a natural filter bed. Before pressing the bombilla against the leaves, dampening them with cool water helps to keep the filter bed in place.

- Finally, the cebador adds the warm water. The water is warm (around 60-70°C or 140-160°F) rather than boiling, because boiling water may cause the gourd to crack—and your lips simply won’t forgive you for drinking boiling water through a metal straw!

In most of the world’s ceremonies, the host goes last, always serving the guests first. The mate ceremony doesn’t work that way. That first gourd full of yerba mate is most likely to get little leaf particles in the bombilla, and can be bitter. So the cebador takes one for the team and drinks the first gourdful.

After polishing off the first round, the cebador adds more warm water and passes the gourd to the guest to his or her left. The guest empties the gourd completely (you share the gourd, not the drink!), being careful not to jiggle around the bombilla and upset the filter bed, and passes the gourd back to the cebador.

The process repeats, moving clockwise around the participants, with everyone getting a full gourd of yerba mate. A gourd full of leaves should last for at least 15 servings before it loses its flavor and becomes flat.

What’s the Healthiest Tea?

Unlike some of the other questions I address here, this one has a very straightforward answer. The healthiest tea is the one you’ll actually drink.

Figuring out which specific tea has the most health benefits is a complex task. Most styles and brands don’t have lab analysis of their antioxidant content, caffeine levels, and other details. Many scientific reports and studies are being misinterpreted, and others are being oversimplified.

Here’s the bottom line, though: if you don’t like the taste of a tea, you won’t want to drink it. You’ll have fewer cups per day. You’ll use smaller cups. You’ll use less leaf.

But if there’s a variety that has a bit less benefit — perhaps half of those healthy amino acids you’re after — and you love the flavor, you’ll drink more. You’ll use one of those big American mugs instead of a dainty British teacup. You’ll make it stronger. You’ll sneak in extra cups because you enjoy it. And even though each cup has less of what you’re trying to get, you’ll get a lot more.

So if your goal is to drink more white tea, don’t just buy a pound of the first (or cheapest) white tea you find and choke it down. Experiment! Try a variety of white teas and buy the one you really enjoy drinking. If you want green tea and you don’t like the Chinese variety you tried, try a few Japanese green teas.

Whether you’re in this for the health benefits or for because you enjoy tea, it’s fundamentally all about the taste!

How much caffeine is in my tea?

I wish there was a simple answer to this question. It would be ever so cool if I could just say, “black tea has 45 mg of caffeine per 8-ounce cup.” In fact, a number of people say it actually is that simple. Unfortunately, they’re wrong.

This graph came from the front page of the eZenTea website:

And this one is from a tweet from SanctuaryT (it said, “Finally, the truth about #tea and #caffeine!”):

They make it pretty simple, right? But that’s not very useful when they disagree with each other! The first chart shows the caffeine in green tea at 20 mg/cup and white tea at 10 mg/cup, showing that white tea has half as much caffeine as green tea. The second chart shows green tea at 25 mg/cup and white tea at 28 mg/cup, indicating that white tea has 12% more caffeine.

Then we get confusing (and frankly pretty silly) charts like this one from HellaWella:

All three charts have green tea in the same basic range (20-25 mg/cup), but the HellaWella chart breaks out black tea (which is 40-42 mg/cup in the other two charts) into “brewed tea” at 47 mg/cup and “brewed imported tea” at 60 mg/cup. Huh? “Imported”? HellaWella’s “about” page doesn’t say what country they’re from, but I’m going to guess from the spellings that they’re from the U.S. Sure, there are few small tea plantations in the U.S., but I would venture to guess that approximately zero percent of casual tea drinkers have ever had a domestically grown tea. In America, pretty much all tea is “imported.”

So why the discrepancies?

Because the people making these charts (a) don’t explain their methodology and/or (b) don’t understand tea.

As I explained in my three-part caffeine series (here’s part 1), green, white, oolong, black, and pu-erh tea all come from the same species of plant (Camellia sinensis), and in some cases, the same actual plant. We carry a black and a green Darjeeling tea that are picked from the same plants, but processed differently. No part of that process creates or destroys caffeine.

Let me make that clear: let’s say you pick a bunch of tea leaves on your tea farm. You divide them up into four equal piles. You turn one pile into green tea, one into white tea, one into black tea, and one into oolong tea. When you’re done, you make a cup of tea from each. Assuming you use the same water at the same temperature, use the same amount of leaf per cup, and steep them for the same time, they will all have the exact same amount of caffeine.

If that processing doesn’t change the caffeine content, what does?

- The part of the plant that’s used. Caffeine tends to be concentrated in the buds and leaf tips. A high-quality golden or white tea made from only buds will have more caffeine than a cheap tea made with the big leaves farther down the stem.

- The growing conditions. Soil, rainfall, altitude, and many other factors (collectively known as terroir) all affect how much caffeine will be in the tea leaves.

- The time of year the leaves were harvested. Tea picked from the same plants several months apart may have dramatically different amounts of caffeine.

- How long you steep the tea. The longer those leaves sit in the water, the more caffeine will be extracted into your drink.

- How much leaf you use in the cup. Use more leaves, get more caffeine.

- How big the cup is. This seems ridiculously obvious, but it’s something a lot of people miss. Anyone who went to elementary school in the United States knows that one cup = eight ounces. However, a four-cup coffee maker doesn’t make 32 ounces (8 x 4); it makes 24 ounces. They decided their coffee makers sound bigger if they use six-ounce cups.

Even if you and I measure the same amount of leaf out of the same tin of tea, your cup might have twice the caffeine of my cup, depending on how we like to fix it. Unless we both precisely followed the ISO 3103 standard for brewing the perfect cup of tea.

Unfortunately, the lab tests to assess caffeine content are expensive, so most tea shops never test their teas. On top of that, people can’t seem to agree on how to brew the tea they are testing. I read one study where every tea was brewed for five minutes in boiling water. That’s consistent, but it’s not realistic. You don’t brew a Japanese green tea that way, or you’ll have a bitter, undrinkable mess. Another, by Kevin Gascoyne, tested tea as most people drink it (e.g., black tea in boiling water, white tea in cooler water). That’s better but even still, Kevin’s way of brewing a particular tea may not be the way I do it.

The bottom line is that every tea is different. Very different. In fact, Kevin tested two different sencha teas and one had four times the caffeine of the other. If someone shows you a handy-dandy chart that indicates exactly how much caffeine a cup of tea has (as opposed to showing a range), it’s wrong.

While writing this blog post, I was drinking green rooibos from South Africa, which has no caffeine at all. It is a non-oxidized “redbush” tea has a much softer flavor than red rooibos. I brewed this cup for 4:00 using boiling water. It’s a remarkably forgiving drink, and I’ve steeped it for as long as 10 minutes without ruining it. It’s usually good for at least two infusions.

Caffeine Math: How much caffeine is in a tea blend?

For some reason, it seems like I write a lot about caffeine on this blog. My three-part series on the subject is the most popular thing I’ve ever posted. My recent post about theanine talked about caffeine as well. One thing I haven’t addressed in detail is what happens to caffeine content when you blend tea with something else.

The first thing we have to do is clear our minds of preconceptions. Remember that there’s no simple formula saying that one kind of tea has more caffeine than another (see my caffeine myths article for details). And resign yourself to the fact that there’s no way short of spending a couple of thousand dollars on lab tests to determine how much tea is in a commercial blend, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment.

Let’s start with an example. Assume you have a tea you enjoy. You use two teaspoons of tea leaf to make a cup, and we’ll say this tea gives you 20mg of caffeine. You decide to use this tea in a blend. What happens to the caffeine level?

Ingredient blends

If you blend with other bulk ingredients, the caffeine calculations are simple ratios. If you blend the tea 50/50 with peppermint, then instead of two teaspoons of tea (20mg of caffeine), you’re using one teaspoon of tea (10mg of caffeine) plus one tablespoon of mint (no caffeine). You’ve cut the amount of caffeine in half. If your blend is 1/3 ginger and 2/3 tea, it will have 2/3 as much caffeine as the straight tea.

If you’re blending tea with other tea, the ratios work the same way. Blend together two tea styles with equivalent caffeine levels and the result will have the same amount of caffeine as the original tea blends.

All of this is contingent upon your measuring techniques. It becomes more complicated if you blend by weight instead of volume. Put together a cup of green tea and a cup of peppermint, and two teaspoons of the blend will contain (about) one teaspoon of tea and one teaspoon of mint. If you put together an ounce of gunpowder green tea and an ounce of peppermint leaves, the result is very different. Gunpowder tea is very dense, and peppermint leaves are light and fluffy. Two teaspoons of that mixture might only have a half teaspoon of tea, which means a quarter of the caffeine.

Extracts and oils

In many commercial tea blends whole ingredients like chunks of berry, flakes of cinnamon, and bits of leaf are more for looks than flavor. Soak a strawberry in hot water for three minutes and you’ll see what I mean. The real flavoring in those blends comes from extracts and essential oils that are sprayed on the tea leaves. In that case, the caffeine content is pretty much unaffected. A teaspoon of flavored tea leaves has the same caffeine as a teaspoon of unflavored tea leaves.

A little tea blending secret: sometimes the chunks of fruit in the tea really are chunks of fruit, but they’re not what you think they are. Tea blenders can purchase small chunks of dried apple that are sprayed with (or even soaked in) flavorings or extracts. Your piña colada blend might just be apple bits flavored with coconut and pineapple extracts. There’s very little flavor in the dried apple, so all you’re getting is the flavoring that was added. Why use them at all? Because it’s easy to experiment with, it doesn’t require the tea company to invest in leaf-spraying equipment, and it adds some visual variety to the blend. The chunks can even be colored.

A couple of real-world examples

Let’s start with genmaicha. This is a classic Japanese blend of green tea and roasted rice. I started with a tablespoon of my favorite genmaicha:

The base tea in this blend is sencha, which is fairly easy to recognize from the color and needle shape of the leaves. I don’t know the exact caffeine content of the sencha, but I can do a bit of Googling and come up with an estimate. Let’s go with 30mg per cup. Now, we’ll separate the tea leaves from the rice:

The main thing I learned from this exercise is that I don’t have the patience to pick all of the rice out of a tablespoon of genmaicha! The separation I did showed that a tablespoon of this particular genmaicha contained about 1/3 tablespoon of rice and 2/3 tablespoon of sencha. Since rice has no caffeine, that means a cup of this genmaicha probably has about 20mg of caffeine in it.

I was going to try the same experiment with a Moroccan mint tea, but found that the one I have on hand has no peppermint leaves. It appears to contain only tea leaves and mint extract. That means it has the same caffeine level as the tea used to make it — in this case a gunpowder green tea.

Doing the math

I don’t think you actually have to do much math to estimate caffeine levels. It’s imprecise at best because tea leaves don’t come labeled with their caffeine content. But if you look at a tea blend and it appears to be about half tea leaves and half something else, it’ll have about half the caffeine of the tea alone. Some blends I’ve looked at lately appear to have very little tea leaf — those might as well be decaffeinated tea! Others, like the Moroccan mint I mentioned a moment ago, are almost entirely tea, so treat them just as you would unflavored tea.

Argentina and Yerba Maté: Stop 8 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

While Europe was getting hooked on coffee and Asia was drinking tea, the people of Argentina and Paraguay were enjoying their own indigenous source of caffeine: yerba maté.

Yerba maté comes from a plant called Ilex paraguariensis, a species of holly which contains caffeine and other xanthines. Maté is a traditional beverage throughout South America, typically served hot (well, “warm” by American standards) and shared among friends from a gourd and bombilla (metal or cane straw).

The matés we tasted were:

- Traditional green yerba maté (organic)

- Roasted yerba maté

- Montana huckleberry maté

- Carnival maté

- Eye of the Storm (our house blend minty maté)

Although when it comes to caffeinated drinks, Argentina is mostly known for its yerba maté, the country is the world’s 9th largest producer of tea, with an annual production of about 60,000 tons. Most of that tea is used in blends and iced teas, and it’s pretty rare to find an Argentinian tea on the menu at a tea bar.

In land area, Argentina is the world’s 8th largest country, covering over a million square miles. Their population is just over 40 million, and the main language is Spanish.

Yerba Maté

The word maté actually means “gourd,” a reference to the vessel traditionally used when drinking yerba maté in most of South America. In Paraguay, on the other hand, they often drink their maté cold (they call it tereré) from a guampa, a drinking vessel made from an ox horn.

The total world production of yerba maté is about 500,000 tons, of which about 290,000 tons comes from Argentina: almost five times their annual tea production. The rest is almost all grown in Brazil and Paraguay. This makes it about a $1.4 billion market (in U.S. dollars) — much bigger than the rooibos market we talked about last week. The majority of the maté is consumed in South America, with the largest outside buyer being Syria.

Maté is usually produced like a green tea, with minimal oxidation. The gourd is packed about half full with leaves in an elaborate ritual, and then filled the rest of the way with water at about 150 degrees F. Argentinian children enjoy maté, too, usually prepared with milk.

In the U.S., maté is more often prepared like tea, by steeping in hot or boiling water. A bit of sugar can help to cut the bitterness caused by the hotter water.

We tasted both a plain maté and one of our house blends with peppermint and spearmint added (that one is yummy iced!).

Roasted Maté

It is becoming increasingly popular to roast the maté, producing a drink that is darker and richer. The taste of roasted maté is often compared to coffee or chicory. We tasted a plain roasted maté plus two flavored ones: a “carnival” maté with caramel and Spanish safflower, and a Montana huckleberry maté.

Caffeine and Maté

It was long thought that maté contained a chemical called mateine, similar to caffeine and a member of the xanthine family. Recent research has shown that mateine actually is caffeine, and it just showed up differently in lab tests because of other compounds present in the maté.

Yerba maté contains three different xanthines: caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline. The total caffeine content is higher than a typical cup of tea, but less than a strong coffee. The way the maté is prepared has a great effect on the caffeine content: the temperature of the water, the steep time, and the amount of leaf used all interact to influence how much caffeine is extracted from the leaves into the drink.

When I have some more time, I’ll write a post detailing and illustrating the maté ceremony.

This was the eighth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from February.

The Rooibos of South Africa: Stop 7 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

If you’re looking for a drink with all the health benefits of tea, a similarly great taste, but no caffeine, look to South Africa! Rooibos is made from the South African red bush (Aspalathus linearis). Using rooibos instead of tea is a great way to enjoy a caffeine-free hot (or iced) drink without using any chemical decaffeination process. Rooibos is full of antioxidants, Vitamins C and E, iron, zinc, potassium, and calcium. It is naturally sweet without adding sugar.

Rooibos grows only in the Western Cape of South Africa, and a similar plant called honeybush (the Cyclopia plant) grows in the Eastern Cape. Its flowers smell of honey, hence the name. The taste of honeybush is similar to rooibos, though perhaps a bit sweeter. Like rooibos, honeybush is naturally free of caffeine and tannins; perfect for a late-evening drink.

The teas we tasted were:

- Red rooibos (organic)

- Green rooibos (organic)

- Honeybush (organic)

- Jamaica red rooibos (organic, fair trade)

- Bluebeary relaxation (organic, fair trade)

- Iced rooibos

- Cape Town Fog (a vanilla rooibos latte!)

South Africa, as the name implies, sits at the very southern tip of the African continent. It completely surrounds a small country called Lesotho. South Africa covers 471,443 square miles (about three times the size of Montana) and has a population of 51,770,000 (a bit more than Spain). Despite wide open spaces in the middle of the country, the large cities make it overall densely populated.

The country has the largest economy in Africa, yet about 1/4 of the population is unemployed and living on the equivalent of US $1.25 per day.

Red rooibos

Rooibos isn’t a huge part of the South African economy. It does, however, employ about 5,000 people and generates a total annual revenue of around US $70 million, which is nothing to sneeze at. The plant is native to South Africa’s Western Cape, and the country produces about 24,000,000 pounds of rooibos per year.

The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans. In the U.S., it’s pronounced many different ways but most often some variant of ROY-boss or ROO-ee-bose.

I’ve written quite a bit about red rooibos in several posts — and about the copyright issues — so I won’t repeat it all here. Rooibos is also great as an ingredient in cooking: see my African Rooibos Hummus recipe for an example.

Green rooibos

Green rooibos isn’t oxidized, so it has a flavor profile closer to a green tea than a black tea. Again, I’ve written a lot about it, so I’ll just link to the old post.

Honeybush

Honeybush isn’t one single species of plant like rooibos. The name applies to a couple of dozen species of plants in the Cyclopia genus, of which four or five are used widely to make herbal teas. Honeybush grows primarily in Africa’s Eastern Cape, and isn’t nearly as well-known as rooibos.

It got its name from its honey-like aroma, but it also has a sweeter flavor than rooibos. It can be steeped a long time without bitterness, but I generally prefer about three minutes of steep time in boiling water.

Jamaica Red Rooibos

I decided to bring out a couple of flavored rooibos blends for the tasting as well. The first is Jamaica Red Rooibos, a Rishi blend. It has an extremely complex melange of flavors and aromas, and is not only a good drink, but fun to cook with as well (see my “Spicing up couscous” post).

Jamaica Red Rooibos is named for the Jamaica flower, a variety of hibiscus. The extensive ingredient list includes rooibos, hibiscus, schizandra berries, lemongrass, rosehips, licorice root, orange peel, passion fruit & mango flavor, essential orange, tangerine & clove oils

BlueBeary Relaxation

BlueBeary Relaxation one of the blends in our Yellowstone Wildlife Sanctuary fundraiser series (the spelling “BlueBeary” comes from the name of one of the bears at the Sanctuary). It’s an intensely blueberry experience that’s become a bedtime favorite of mine. It’s like drinking a blueberry muffin!

Iced rooibos

To make a really good cup of iced rooibos, prepare the hot infusion with about double the leaf you’d use normally, because pouring it over the ice will dilute it. Both green and red rooibos make great iced tea. I prefer both styles unadulterated, but many people drink iced red rooibos with sugar or honey.

Cape Town Fog

This South African take on the “London Fog” is a great caffeine-free latte. To prepare it, you’ll want to preheat the milk almost to boiling. If you have a frother of some kind, use it — aerating the milk improves the taste. Steep the red rooibos good and strong, and add a bit of vanilla syrup or extract. We use an aged vanilla extract for ours. Mix it all up, put a dab of foam on top if you frothed the milk, and optionally top with a light shake of cinnamon.

This was the seventh stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from February.

Seasons of Tea

As my tea bar does more direct tea buying (as opposed to buying through distributors), I have an opportunity to taste some absolutely fascinating teas. As I tasted some estate-grown Darjeelings the other day, I was reminded of how much difference the picking time makes on the character of the tea.

The three teas on the right side of the picture above are all Darjeeling teas from the Glenburn estate. The terroir is identical. It’s the same varietal of Camellia sinensis var sinensis (the Chinese tea plant) — all FTGFOP1 clonals. They are all black teas. They were steeped for the same amount of time using the same water at the same temperature. I used the same amount of tea leaf for each cup. What’s the difference?

- The light golden tea second from left is a first-flush Darjeeling, picked on March 20th. At that time of year, the spring rains are over and the tea plants are covered with fresh young growth. The tea is very light in color, and the flavor is mild but complex with a touch of spiciness. Although all four of the teas in the picture were steeped 2-1/2 minutes, I actually prefer my first flush Darjeelings steeped for a considerably shorter time (although everyone has different opinions on that). I’m drinking a cup as I write this, and it’s just about right at a minute and a half.

- The amber cup to the right of the first-flush is a second-flush, picked in June. The drier summer climate produces a heartier cup of tea, with a flavor often described as “muscatel.” There is more body and a bit more astringency as well.

- The darkest cup of tea on the far right is called an Autumnal Darjeeling. This one was picked on November 10th. By then, the monsoons are over and the new growth on the tea plants has matured. An autumn-picked Darjeeling will be darker in color, stronger in flavor, and fuller-bodies, but without as much of the spicy notes Darjeelings are known for.

These seasonal differences account for massive differences in caffeine content as well. Early in the season, tea plants will have more caffeine concentrated in the new growth, which is what’s picked for the delicate high-end teas. The data that Kevin Gascoyne presented at World Tea Expo last year showed a 300% increase in caffeine between two pickings at different times of year in the same plantation.

Comparing Darjeeling teas can be difficult, as much of the “Darjeeling” tea on the market isn’t authentic. According to this 2007 article, the Darjeeling region produces 10,000 tonnes of tea per year, but 40,000 tonnes is sold around the world. Even if you don’t consider the local consumption, that means 3/4 of the tea sold as Darjeeling is grown somewhere else. That’s why it’s so important to buy from a trusted source.

When selecting teas, we tend to look first at the production style (black, green, white, oolong, pu-erh), and then for the origin (a Keemun black tea from China is quite different from an Assam black tea from India). As consumers, we rarely know the exact varietal of the plant or the picking season, but those factors are every bit as important to the final flavor.

I suppose the main message of this article is that you can’t judge a tea style on a single cup. You may love autumnal Darjeeling and dislike first-flush. You may enjoy a second flush from Risheehat and not the one from Singbulli.

Rooibos: The African Red Bush

How have I been at this blog for so long without writing about rooibos? Oh, I know this blog is about tea, and I did write a post about green rooibos last year, but I haven’t covered straight red rooibos yet.

Rooibos comes from a bush called Aspalathus linearis, which grows in the west cape of South Africa. The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans.

Rooibos is also often called “red tea,” but most tea professionals shy away from that name for several reasons:

- The term “red tea” is used by the Chinese to refer to what we call “black tea.” No sense having two different drinks with the same name.

- Rooibos isn’t tea, since it doesn’t come from the Camellia sinensis plant. Instead, it is a tisane or herbal infusion.

- Rooibos only has that rich red color when it’s processed like a black tea. Green rooibos is more of a golden honey-colored infusion.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Unlike “real” tea, which all has caffeine, rooibos is naturally caffeine-free. Since the flavor is similar to a mild black tea, this makes it a favorite bedtime beverage for many tea drinkers. Rooibos is also high in antioxidants.

Herbalists make many claims about the health properties of the rooibos tisanes. The Web site for the South African Rooibos Council (SARC), in fact, has very little information that isn’t in some way tied back to health claims. There are more and more studies being done, but available data are lacking in specifics (in my opinion, anyway) so I’m not going to quote any of those there. Feel free to check SARC’s site for lots of studies.

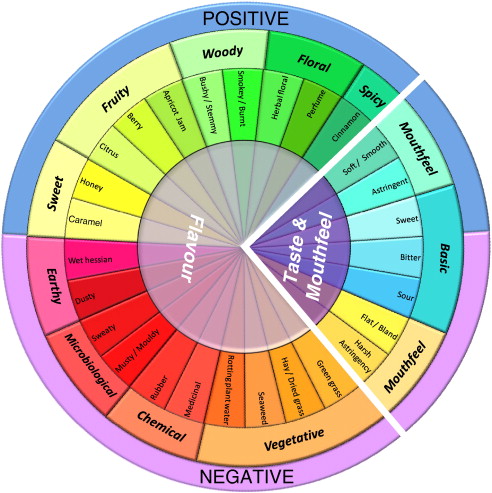

I don’t mean to imply that rooibos is only about the health benefits. It is, in fact, a very tasty drink. Most rooibos drinkers in the U.S. enjoy it straight or with a bit of sweetener (honey or sugar). In South Africa, it is commonly served with a bit of milk or lemon as well as honey. A group funded by SARC and Stellenbosch University has recently developed a “sensory wheel” for rooibos, describing both the desirable and undesirable aspects of flavor and mouthfeel. If you are interested in more information, click on the wheel below.

Rooibos Sensory Wheel as described in the article “Sensory characterization of rooibos tea and the development of a rooibos sensory wheel and lexicon,” available on Science Direct. Click the wheel above to view the article — there is a charge for the full text version.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Compared to tea, rooibos is a pretty small market. South Africa’s annual rooibos production is about 12,000 tons. That output is about equivalent to annual tea production of the Darjeeling region of India, or about a tenth of the tea production of Japan (the 8th largest tea producing country). Nonetheless, rooibos is important to South Africa, employing about 5,000 people and generating about $70 million in revenues.

The leaves of the rooibos bush are more like needles than the broad leaves of a tea plant. To produce red rooibos, the leaves are harvested, crushed, and oxidized using a process based on the one used in making Chinese black tea. Typically, the leaves are sprayed with water and allowed to oxidize for about 12 hours before being spread out in the sun to dry.

Green rooibos, as the name implies, is unoxidized or very lightly oxidized, and is processed more like a green tea.

For more information about the rooibos industry, I recommend the article Disputing a Name, Developing a Geographical Indication, from the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Legend says that tea originated in China in 2737 B.C., over 100 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built. In this first stop on our

Legend says that tea originated in China in 2737 B.C., over 100 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built. In this first stop on our