Blog Archives

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 1

Posted by Gary D. Robson

This is one of the stories from my book, Myths & Legends of Tea Volume 1. I will post the conclusion tomorrow [Update: here it is]. In the book, each story is followed by notes about the tea and how to prepare it. I hope you enjoy the stories!

To read more about Myths & Legends of Tea, download a sample chapter, or buy a copy (paperback, Kindle, or Apple iBook), please visit the main book page!

The Iron Goddess of Mercy

China, 1761

It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of Wei.

Wei lived in Anxi Country in the Chinese province of Fujian. People there were struggling with hard times. Fujian, they say, is eight parts mountain, one part water, and one part farmland. Wei’s tiny village was no exception. He and his neighbors grew what they could. A bit of wheat, a bit of rice, and a few sweet potatoes were enough for most of them to get by.

Their favorite crop was tea. They worked hard to produce good tea, using the complex oolong production style. Their process wasn’t bad but the result was usually mediocre, as it came from poor stock.

“Oh, well,” they used to say. “You can’t get silk from an earthworm.”

Each week, Wei would go to market in the city. Each week, he passed an old temple that had fallen into disrepair. The pathway was overgrown, the gates had fallen, and it appeared that nobody had worshipped there in a very long time. It was such a part of the scenery that Wei walked by it without even seeing it.

Like the rest of his village, Wei was a Buddhist. It’s difficult to describe how Buddhism works to Westerners like us, as the Buddha himself isn’t considered a god but an enlightened being. What we often refer to as gods and goddesses in Buddhism, actual Buddhists would call bodhisattvas. The temple Wei passed each week was built for the Bodhisattva Guanyin, whom you or I might call the Goddess of Mercy.

One particular day – a day that would become a major turning point for Wei, Wei’s village, and lovers of tea everywhere – Wei stopped on the road to rest. Not that stopping on the road was an unusual occurrence. The trip was long and Wei was not as young as he used to be. On this very notable day, however, he stopped right at the pathway to the temple of Guanyin.

After Wei set down his heavy load, he pushed back his hat and wiped the sweat from his forehead. What used to be the temple’s garden was surrounded by a small rock wall, more decorative than functional. It would do no good at keeping out deer or rodents, and in its current tumbledown state, even a rabbit could hop right through in several places.

Once, the flowers and cherry trees of the garden had been carefully-tended, but that was long ago. The undergrowth almost completely obscured the path, bushes had grown tall and scraggly, and the unpruned cherry trees blocked the sun to the flowers. At least, he thought, the wall provides a place to sit and the trees give me shade.

He looked down the pathway, wiped his sleeve across his forehead again, and thought about the temple.

Guanyin is the Goddess of Mercy, he thought. Okay, perhaps he called her a bodhisattva rather than a goddess, but he was, after all, Chinese, and neither goddess nor bodhisattva is a Chinese word, so I shall use the more familiar word in my telling of Wei’s story.

It is not seemly that we should treat Guanyin’s temple with such disrespect, he continued to himself. We should show … well … mercy.

He picked up his wares and continued to market, but his moment of epiphany (or dare I say, enlightenment?) stuck with him throughout the day. The following week, he brought some old gardening tools with him and stashed them beside the pathway on his way to market. He hurried through the selling of what little he had to sell and the buying of what little he could afford to buy, and then he headed home.

When Wei reached the temple, he retrieved his tools and began clearing the path. Carefully, he pruned back the bushes that encroached on the pathway. Thoughtfully, he trimmed the tree branches that overhung the walk. Delicately, he pulled the weeds from the path itself. Soon, the sky began to redden as the sun fell in the west, and he secured his tools behind the rock wall and went home, a bit disappointed that he had cleared only the beginning of the path.

Over the following weeks, Wei repeated the process. Sometimes he would clear the plants. Sometimes he would fix the flat rocks and fill in gaps to smooth the path. Sometimes he would leave the path alone for an evening and work on the wall. He made a special trip with a friend from the village to fix the gate.

This continued until the path was clear all the way to the temple entrance. Pleased with his progress, he lit a candle and stepped into the temple itself.

The sorry state of the exterior was nothing compared to the disrepair of the inside. Webs occupied the corners of the room, and spiders occupied the webs. Dust was everywhere. The offering bowl was reduced to ragged shards, and vines crept in the windows. A mouse skittered across the floor, and a snake watched hungrily from behind the altar. But Wei noticed none of it. All of his attention was drawn to the statue of Guanyin.

There she sat! The center of the temple was dominated by the statue of a beautiful maiden meditating. In her lap she held a fish basket. Although the statue was dirty and old, it was unbroken and the fine details of her necklace and her Tang Dynasty clothing were clear. Wei thought he could see sadness on that lovely face, and it nearly broke his heart.

He stood staring at Guanyin for many minutes, finally breaking his reverie to look about the room. To one side was a painting of Guanyin with a child on each side and a white parrot above. A beetle crawled across the frame. Even the painting looked sad, he thought.

Wei was touched by the experience and vowed that he would get rid of that melancholy look. He continued coming back each week on his way home from market. On one visit, he brought a stick long enough to take down the spider webs. Of course, he carefully took the spiders outside without harming them. Guanyin is, after all, the Goddess of Mercy.

The next week, he brought a broom and swept out the temple. The next, he delicately dusted the statue itself. He found the nest the mice had built and moved it outside. The snake, he scooted out the door with the broom. This had to be repeated several times as snakes can be stubborn once they’ve chosen a home.

The next time he stopped at the temple, he looked at the shattered bowl in front of Guanyin’s statue. He carefully gathered the pieces of the broken offering bowl in the sleeve of his robe and took them home. He set the pieces on his table and studied them. Wei was a simple farmer. He didn’t have the skills to repair the bowl. But perhaps he knew someone who did.

Wei once again gathered up the bowl fragments and carried them to the home of his good friend Wang, the potter. Wang invited Wei into his home and went immediately to the teapot. After all, when a friend visits, it is important to serve them tea.

As the water heated, Wei began to tell Wang about the temple. Wang listened as he carefully measured out the leaves. At first, the tale did not interest him much, for China is filled with old temples and roadside altars. Some are well-kept. Some are not.

As large bubbles began to form and rise through the water (the Chinese people call this stage “fish eyes”), Wang put the tea on to steep. When Wei started to tell him about the offering bowl Wang’s ears perked up.

“I do not know how to fix the bowl,” Wei told him, “and I do not have the money to buy one.”

“Let me look,” Wang said, and Wei spread out the pieces before him. Wang became so engrossed in studying the broken bowl that he almost forgot to pour the tea. He was so distracted that he hardly noticed the muddy flavor and the bitterness of their tea. When you can rarely afford to buy good tea, you soon become accustomed to poor tea.

“Can you repair this,” Wei asked anxiously, “or perhaps make another one like it?”

“Where will you get the money to pay for it?” Wang responded. “I am very busy and must make many bowls to sell so that I can feed my family. And Guanyin’s temple is your project, not mine.”

“You are my friend, Wang. When you were sick last summer, who brought tea and rice for you and your wife? When the monsoon rains came early two seasons ago, who helped you to make a ditch to drain your wheat field and irrigate your rice properly?”

“You are right, Wei. I am sorry. Friends help their friends. I shall make you a proper bowl. I cannot do it today, and maybe not for a couple of weeks, but I will make a bowl that you will be proud to give to Guanyin.”

And so things went. Wei replaced the offering bowl with the one that Wang made him. He pruned the trees. He found an inexpensive incense burner and set it in a nook on the wall. He took a pitcher of water and washed the statue. He kept the pathway clear. He even planted some flowers. And every week he lit incense and meditated before he left.

Tune in tomorrow for the conclusion to Wei’s story!

Oolong-related articles on Tea With Gary

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 1

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 1 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 2

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 2 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

Canon cameras and oolong tea

Why should you drink oolong tea when you’re taking pictures with a Canon camera? Let me explain…

-

The Oolongs of Taiwan: Stop 6 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Taiwan may not have originated oolong tea, but it is definitely at the forefront of oolongs today. At this stop on the tea tour, attendees learned about what oolong tea actually is, and tasted a variety of Taiwanese oolongs, including Bao Zhong, White Tip Bai Hao, and of course Tieguanyin,…

-

Free mystery tea (Tieguanyin)!

A friend stopped by the tea bar the other day and brought a bag of tea from China that a friend had given her. She didn’t know what it was, and she’d had it for five years, so she asked if I’d like to have it.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Mastodon (Opens in new window) Mastodon

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 2

Posted by Gary D. Robson

This is the continuation of yesterday’s post, which is one of the stories from my book, Myths & Legends of Tea Volume 1. In the book, each story is followed by notes about the tea and how to prepare it. I hope you enjoy the stories!

In our story so far, a farmer named Wei has discovered an abandoned temple to Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, and worked tirelessly to restore it to its former beauty.

To read more about Myths & Legends of Tea, download a sample chapter, or buy a copy (paperback, Kindle, or Apple iBook), please visit the main book page!

The Iron Goddess of Mercy

China, 1761

One day, Wei walked into the temple and realized he had done everything he could do. All of the little things were repaired. Everything was clean. The incense was burning and someone – he did not know who – had placed an offering in the bowl. He looked at the statue of Guanyin and thought he detected a trace of a smile. Just a tiny bit. Just at the corner of her mouth. But he didn’t see the sadness he had seen before.

There may actually have been a hint of smile on the statue’s face, or Wei may have been imagining it. It really didn’t matter, though. It brought a real smile to Wei’s face. There’s a special kind of happiness we get from doing things for others, things that bring us no personal benefit. That is what Wei felt as he walked home that afternoon.

That night, as Wei slept, he had a vivid dream. Not like our normal dreams, where things have soft edges and little detail and we forget them as soon as we wake. This dream was crystal clear, and felt like he was actually experiencing it.

Wei stood on the shore of an ocean where a mighty storm was raging. He was on a rock looking down at the powerful waves crashing against the shore. The wind whipped the spray into his face and threatened to knock him from his precarious perch. Although it was daytime, the dark clouds above hid the sun from him, making everything look like it was drawn in charcoal.

He seemed to actually feel the sea water on his skin, hear the howl of the wind and the roar of the surf, smell the salt in the air. Never had he experienced a dream with such clarity, and it made him nervous.

He fell to one knee and braced himself against the wind so that it wouldn’t sweep him into the surf booming against the sharp outcroppings below him. As he knelt there, the clouds parted far out over the water and he saw a beam of sunshine fight its way through. Where it hit the water, the head of an enormous sea dragon breached the surface of the sea, and the furious storm-whipped waves began to calm around its mighty neck. As more of the dragon crested, Wei saw someone standing on its back, wearing flowing white robes.

As the dragon approached, the calm water and the beam of light came with it. Soon, Wei could make out the woman riding upon the dragon. It was Guanyin, carrying a willow branch in her right hand and a jar of clear water in her left. Although water coursed from the back of the sea dragon, Guanyin’s hair and robes were dry. On her face was an expression so serene, so calm, that Wei did not fear the monstrous beast that towered high over the shore. Guanyin stood effortlessly, her dry feet showing no signs of slipping on the wet scales of the dragon’s back.

When the dragon approached his rock, Wei was encompassed by the beam of light. The crashing of the waves ceased and the world around him suddenly felt like it was painted in delicate watercolor. Tranquility settled over him, and he rose to his feet to find himself looking into the eyes of Guanyin. He fell back to his knees and bowed his head.

“Rise,” she told him. He stood awkwardly, intimidated by her presence and the head of the dragon looming over him, water dripping from the barbels alongside the fearsome mouth.

She studied him for a long moment before she spoke. He kept his head down, but could not stop himself from looking at her.

“You are a good man, Wei,” she said. “You have worked long and hard to restore my temple, and you have shown me great respect. What would you ask from me as a reward?”

He responded without stopping to think. “I did what I did because it needed to be done. I did not fix your temple because I sought reward. I fixed it because it was the right thing to do.”

“I know that,” the goddess responded. For the first time, Wei saw a smile on her face, and it brought such joy to his heart that he almost interrupted her. Luckily, he held back, for it is not wise to interrupt the gods. But what reward could compare with bringing a smile to the face of the Goddess of Mercy? No man could ask for more.

“Had you done this for a reward,” she continued, “I would not be inclined to give you one. But your motives are pure and enlightened. Kindness deserves kindness, and for that reason, I shall reward you.

“You did not select a gift, so I have selected one for you. You shall find it behind the temple, shadowed by the large bear-shaped rock. It holds the key to your future and your village’s future, so treat it with care and respect.”

He bowed his head again as the dragon pulled back from the rock upon which he stood. The clouds dissipated from the sky, and the sea became smooth as glass. A single yellow butterfly danced before him as the dragon swam away, gradually disappearing under the water.

Wei stood on the rock, overcome with joy. Slowly, the vision faded and he settled into a deep dreamless sleep.

When Wei awoke in the morning, he lay quietly in his bed, serene and rested. Then the dream came back to him. He leapt out of bed and rushed through his morning routine. He felt no hunger, and took only a moment to eat a half-bowl of rice, barely tasting it as he ate.

He rushed to the temple. How different it looked! The stone wall looked sturdy and solid. Flowers were beginning to bloom in the rays of sunlight that streamed through the neatly-pruned cherry trees, which were showing signs of blooming themselves. The entrance to the temple was inviting, clean, tidy.

Without even pausing to enter the temple and light incense, Wei stepped from the path and circled around behind. He hadn’t ventured here before. It was still wild. A rivulet of water burbled happily down the steep slope, and only a small area was flat and level. In that small area stood the bear-shaped rock that Guanyin had referred to, taller than Wei himself.

He looked eagerly in the rock’s shadow, not knowing what to expect, and saw nothing but dirt, rocks, and a pathetic little sprig of a plant.

I see nothing, he thought. My treasure must be buried.

But as Wei kneeled to start digging, something about the sapling caught his eye. The deep green of the leaves and their slightly jagged edges looked familiar. It was a tea plant! Small, undernourished, with only a few leaves, but a tea plant nonetheless. He dug it up and carefully transplanted it into his garden at home.

For days and weeks, he watered it, tended it, fertilized it, all the while not quite sure if this tiny plant was really his reward from the goddess. The scraggly plant grew quickly into a thick healthy bush. The trunk grew strong and thick; the leaves glossy and bright. He picked a leaf and crushed it between his fingers. The aroma was strong and sweet. It was time.

Carefully, he selected a handful of delicate new buds and the young leaves next to them. He laid them out in the sun to wither, and went to tell his friend Wang about his prize. Wang came back to see the tea bush, and they took the leaves into the house to cool.

“Should I go to the city and find a tea master to help me prepare this properly?” Wei asked his friend.

“No,” said Wang. “Guanyin gave you this tea plant. Meditate as the leaves cool. Clear your mind, and then follow your instincts.”

And so he did. He followed the same process that he always used with the scruffy tea plants that he and his neighbors grew. Tossing, a bit of oxidizing, fixing; he dedicated the next day to working with his prized leaves.

He rolled the leaves as oolong tea makers did – and still do. Not being very skilled at it, he ended up not with neat little balls, but with little curled-up tadpole shapes, which he roasted very lightly. Over the next two days, they dried hard as he looked on impatiently. At last, the leaves appeared ready.

Excited, Wei fetched one of his most prized possessions: a beautiful black iron teapot. He took a small scoop of the leaves and dropped them into the teapot and they made sharp “ping” sounds, almost like iron pieces tumbling into the iron pot. He rushed to get Wang and some of his neighbors. They looked at him dubiously as he chattered on about the visit from Guanyin in his dream. They passed around one of his dried leaves and looked it over uncertainly.

Then he poured the hot water over the leaves in his teapot, and the aroma of the tea struck them. They rushed in to look, to smell, and – when the tea was finished steeping – to taste.

The tea was magical. It had a rich amber color and a bold taste with overtones of honey and spice. They held the liquid in their mouths and it felt smooth and light. The taste lingered long after the tea was swallowed, and it brought what could only be called an energizing calm to the villagers. All of the tea they had ever produced before suddenly seemed inadequate and drab.

Because of the hard dried leaves and their ringing sound when dropped on iron or steel, Wei called the tea tieguanyin, which we translate today as Iron Goddess of Mercy.

As Wei’s tea bush flourished, he took cuttings for his neighbors, his friends, and his own farm. All of the other tea plants in the village were slowly replaced, and he taught everyone in the village how to produce his special tea. Soon there was enough tieguanyin to take to market, and the reputation of the tea spread like fire.

The poor village prospered and expanded, but Wei was always there to remind them to take time for Guanyin’s temple. Together, they expanded the garden around the temple, lovingly planted with the most beautiful and fragrant flowers, the most luscious fruits, and of course, the goddess’ own tea bushes.

They sculpted a streambed for the water flowing down the slopes behind the temple. They directed the water around the bear-shaped rock and past the temple to the front, where the garden filled with the tinkling sound of water over rocks, and made a pool in front, which they filled with koi and lilies. In that magic way that ponds have, it filled itself with frogs, who added their music to the sound of the stream.

Drinking a cup of tieguanyin there made the garden seem brighter and the tea taste better. Life was not always easy in the village, but it was never as hard as it had been before Wei began his work on Guanyin’s temple.

Does that temple still stand? I don’t know. If so, I think you’ll agree that the statue of Guanyin upon that alter must now be smiling as tea lovers the world over enjoy the rich ambrosia that we call tieguanyin.

Oolong-related articles on Tea With Gary

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 1

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 1 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 2

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 2 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

Canon cameras and oolong tea

Why should you drink oolong tea when you’re taking pictures with a Canon camera? Let me explain…

-

The Oolongs of Taiwan: Stop 6 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Taiwan may not have originated oolong tea, but it is definitely at the forefront of oolongs today. At this stop on the tea tour, attendees learned about what oolong tea actually is, and tasted a variety of Taiwanese oolongs, including Bao Zhong, White Tip Bai Hao, and of course Tieguanyin,…

-

Free mystery tea (Tieguanyin)!

A friend stopped by the tea bar the other day and brought a bag of tea from China that a friend had given her. She didn’t know what it was, and she’d had it for five years, so she asked if I’d like to have it.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Mastodon (Opens in new window) Mastodon

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Canon cameras and oolong tea

Posted by Gary D. Robson

I know what you’re thinking. Has Gary lost his mind? Well, you probably think that anyway, but bear with me for a moment here…

If you can name three styles of oolong tea, one of them is probably tieguanyin, also known as Iron Goddess of Mercy. It’s a wonderful, mellow oolong that’s become one of my favorite teas. I’m drinking a cup even as I write this, and the story behind the name will be featured in the first volume of my upcoming Myths and Legends of Tea short story collection.

And if you can name three brands of cameras, one of them is probably Canon. They make a wide range of consumer level cameras, and they’ve been around a long time — since the 1930’s, in fact.

Tieguanyin comes in tightly-rolled leaves. When you steep the tea, those little tadpole shapes open up into full Camellia sinensis leaves. The tea is named for Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, or more correctly, the bodhisattva Guanyin, since Buddhism doesn’t have gods and goddesses in the Western sense. There are a lot of ways to spell tieguanyin, and a lot of ways to spell Guanyin’s name as well.

This brings us to cameras. The Canon company — originally known as Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory — developed prototypes of a camera back in 1933. They named this camera Kwanon, which is an Americanized version of the Japanese transliteration of Guanyin’s name. It was a camera named for the Goddess/bodhisattva Guanyin.

The name of the company is, in fact, a simplified version of the name of its first camera, the Kwanon. So next time you pull out your Canon camera, make sure to brew up a cup of tieguanyin oolong to sip while shooting your photos. I recommend brewing it for around 2-1/2 to 3 minutes in 175 degree water. You can easily use the leaves four or five times. Just add about 30 seconds to the brewing time for each additional steep.

Oolong-related articles on Tea With Gary

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 1

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 1 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 2

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 2 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

Canon cameras and oolong tea

Why should you drink oolong tea when you’re taking pictures with a Canon camera? Let me explain…

-

The Oolongs of Taiwan: Stop 6 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Taiwan may not have originated oolong tea, but it is definitely at the forefront of oolongs today. At this stop on the tea tour, attendees learned about what oolong tea actually is, and tasted a variety of Taiwanese oolongs, including Bao Zhong, White Tip Bai Hao, and of course Tieguanyin,…

-

Free mystery tea (Tieguanyin)!

A friend stopped by the tea bar the other day and brought a bag of tea from China that a friend had given her. She didn’t know what it was, and she’d had it for five years, so she asked if I’d like to have it.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Mastodon (Opens in new window) Mastodon

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Spelling Madness: Tieguanyin

Posted by Gary D. Robson

In my first day at the 2013 World Tea Expo, I believe I have seen “Tieguanyin” (a wonderful oolong often called “Iron Goddess of Mercy” in English) spelled at least six different ways. In fact, a quick scan of this blog shows that I have spelled it at least three different ways. Tieguanyin, Tie Guanyin, Tae Guan Yin, Ti Kuan Yin, Tie Gwan Yin, Tie Kwun Yin… which one is right?

In reality, none of them are “right.” The name of the tea is Chinese, which is written in Chinese characters. Even in Chinese, there are two different ways to write it (鐵觀音 in traditional Chinese and 铁观音 in simplified Chinese). Some of the sounds in Chinese don’t translate clearly and unambiguously into English, and translations vary over time as well.

How important is it to have a consistent standardized spelling? I think a quick Google experiment will solve that. Let’s try Googling some different spellings and see how many hits we get (NOTE: I did this in 2013. Your mileage may vary):

- tieguanyin: 483,000 results

- tie guanyin: 776,000

- tie guan yin: 488,000

- ti kuan yin: 379,000

- tie kwun yin: 1,200,000

- tae guan yin: 39,000

And when I Googled “Iron Goddess of Mercy,” I got 341,000 results.

I’m not sure how much this reflects how common any given spelling is, and how much it reflects how good Google is at guessing what you mean. The Wikipedia entry for Tieguanyin came up as the top result for almost all of those searches, even though the article doesn’t use most of those spellings. How can we expect to reach agreement on the spelling of the name when producers can’t reach agreement on how much to oxidize the tea?

As with most ambiguous names, the best way to handle it is to pick a spelling and stick with it, something I’m still struggling with myself. You’ll never change the rest of the world, but at least you’ll be consistent.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Mastodon (Opens in new window) Mastodon

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

All the Tea in China: Stop 1 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Posted by Gary D. Robson

Legend says that tea originated in China in 2737 B.C., over 100 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built. In this first stop on our tasting tour, we explored China’s best-known tea growing areas in Yunnan, Anhui, Zhejiang, and Fujian provinces. We also took a look at traditional Chinese teaware, including gaiwans and guangzhou teapots.

Legend says that tea originated in China in 2737 B.C., over 100 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built. In this first stop on our tasting tour, we explored China’s best-known tea growing areas in Yunnan, Anhui, Zhejiang, and Fujian provinces. We also took a look at traditional Chinese teaware, including gaiwans and guangzhou teapots.

The teas we tasted were:

- Organic Longjing Dragonwell (green)

- Organic Pinhead Gunpowder (green)

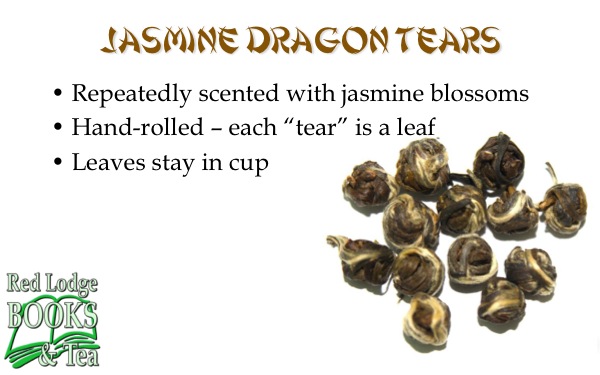

- Jasmine Dragon Tears (green)

- Silver Needle (white)

- Organic Shui Xian Wuyi Oolong

- Organic Keemun Mao Feng (black)

- Organic Golden Yunnan (black)

We started out by taking a look at the legend of the history of tea, going back to Emperor Shennong in 2737 B.C., and then talking about the major tea growing provinces of China. Four provinces were represented in our sampling: Yunnan, Anhui, Zhejiang, and Fujian. Obviously, this is just a beginning, but in a single short class, we can’t hit them all.

After the background was covered, including varietals of the tea plant, we launched into the individual teas, organized by style.

White Tea

First was white tea, the most lightly processed. I chose a Silver Needle blend from Rishi instead of a single-origin tea for this one mostly because our focus was comparing Chinese white tea with green and oolong teas. At some point down the road, we’ll do a comparative white tea tasting where the focus will be on terroir and origin.

One of the bullet points on the slide is an important one: busting the caffeine myth of white tea. The fact that this tea is made from early-picked buds means that there is a high concentration of caffeine. The preparation style does nothing to change that. The longer steep times we typically use on white tea just accentuates this.

We steeped the tea for five minutes in 165 degree water.

Green Tea

I chose three different green teas for the tasting. Each brought something completely different to the party.

First – a straight green tea very typical of Chinese fare, with a history dating back well over a millennium. The name of the tea comes from the finely-rolled leaves resembling gunpowder.

We steeped the gunpowder tea for three minutes in 175 degree water.

I simply couldn’t resist including the original story (fable?) of Longjing tea here, which I’ll be covering in much more detail in the future. Of all of the green teas I’ve tried, this is the one I keep coming back to as my favorite.

We steeped the dragonwell tea for three minutes — although I only do two minutes when I’m brewing it for myself — in 175 degree water.

And finally, we come to the only flavored tea of the evening. We followed tradition with this tea, placing seven tears in each cup and sipping the tea as the leaves unfurl. Unlike all of the other teas we tasted, this one didn’t have a fixed steeping time. Everyone began sipping after a minute or two and kept sipping as the character changed over the next few minutes. We used 175 degree water.

Oolong Tea

We could have easily set up an entire evening just tasting Chinese oolongs (we are, in fact, doing this with Taiwanese oolongs on March 29), but for tonight we chose only one: an oolong from the Wuyi mountains.

It was a very difficult choice deciding which oolong to include. My first temptation was Tieguanyin (Iron Goddess of Mercy), but since I had two rolled teas already I decided to go with an open-leaf oolong.

We brewed this for three minutes in 195 degree water.

Black Tea

And finally, we moved on to black tea. Choosing only two black teas to represent China wasn’t easy (although it was a lot easier than choosing a single oolong), so I simply went with my two “leaf and a bud” favorites: one fully oxidized rich black with overtones of red wine (Keemun Mao Feng) and one lightly oxidized golden tea from Yunnan.

This was another case where I steeped the teas both at three minutes in boiling water for a better comparison, but when I drink them myself I prefer about 2:30 for the Keemun and 4:00 for the Yunnan.

We closed out the evening with a discussion of steeping times, water temperatures, multiple infusions, and other factors involved in preparing a great cup of tea. As always, I ended with the admonition to ignore the Tea Nazis and drink your tea however you like it.

If you live in the area and were unable to attend this session, I sure hope to see you at one of our future stops on our World Tea Tasting Tour. Follow the link for the full schedule, and follow us on Facebook or Twitter for regular updates (the event invitations on Facebook have the most information).

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Mastodon (Opens in new window) Mastodon

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in World Tea Tour

Tags: Anhui, Caffeine, China, dragonwell tea, Fuding Da Hao, Fujian, Golden Yunnan tea, gunpowder tea, Iron Goddess of Mercy, jasmine dragon tears, jasmine tea, Kangxi, Keemun, Keemun Mao Feng, Longjing, Menghai Da Yeh, narcissus tea, Qianlong, Shennong, Shui Xian, silver needle, steep time, tea, tea tasting, Temple of Heaven gunpowder tea, TieGuanYin, Wuyi oolong, Yunnan, Zhejiang

Free mystery tea (Tieguanyin)!

Posted by Gary D. Robson

A friend of mine stopped by the tea bar the other day. Unlike most tea bar visits from friends, Wanda brought tea in with her. It was a bag of tea from China that a friend had given her. She didn’t know what it was, and she’d had it for five years, so she asked if I’d like to have it.

I cut the bag open and poured out a bit of the tea. It was full rolled leaves; not rolled tightly into balls like Dragon Tears or gunpowder tea, but pretty dense nonetheless. The leaves were hard; dropping them into bowl made a pinging sound. The color was a bit darker than a typical green tea, and the smell reminded me of the Huang Jin Gui oolong we carry at the tea bar.

I brewed a cup, using a bit more tea than I usually would because of the age, and decided it was definitely a oolong, but I couldn’t quite identify it. Good packaging, by the way. Five years old, and it still tasted good.

Here’s where Facebook comes in handy. I took a picture of the large print on the top of the bag (the photo that’s now on this page), posted it on Facebook, and asked if anyone could identify it. Within about 20 minutes, I had my answer: Iron Goddess of Mercy, a lightly oxidized oolong with a unique aroma. After enjoying it for a few days, I started hunting for a good one to carry at the tea bar, and I’m excited to have a fresh batch coming in next week. Given how good the five-year-old stuff at home is, I have a feeling I’m really going to love the fresh tea.

Update 2014: Iron Goddess has indeed become one of my favorite teas, and was one of the most popular teas in the tea shop.

Iron Goddess of Mercy (called “tieguanyin” in Chinese) originated in Anxi, in the Fujian province of China. Today, it is produced in quite a few other areas of China and Taiway. The one we sell at our tea bar is a medium-roasted variety from Nantou, Taiwan. I’ve used the leaves for three infusions without loss of flavor, and I’ve been told they’re good for as many as seven.

The processing of tieguanyin is complex. Traditionally, it follows these steps:

- Picking – usually done early in the day when it is sunny

- Sun drying (“withering”) – Done before sunset the same day as the picking

- Cooling (“cool green”) – Done overnight, along with the tossing

- Tossing (“shake green”)

- Withering/partial oxidation – Done the day after picking

- Fixing

- Rolling/kneading

- Drying

- Roasting

There are several conflicting legends regarding the origin of Iron Goddess of Mercy, all recounted on the Chinese Tea Culture site. Personally, I much prefer the Wei Yin legend. I don’t know that it has any more veracity, but it’s a better story. That’s the one I used as the basis for my version of the Iron Goddess story, told in my book, Myths & Legends of Tea, volume 1.

Oolong-related articles on Tea With Gary

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 1

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 1 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

The Iron Goddess of Mercy – Part 2

The Iron Goddess of Mercy Part 2 — China, 1761 — It was the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, but our story concerns no emperors, warlords, or nobles. It is just a tale of a humble farmer by the name of…

-

Canon cameras and oolong tea

Why should you drink oolong tea when you’re taking pictures with a Canon camera? Let me explain…

-

The Oolongs of Taiwan: Stop 6 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Taiwan may not have originated oolong tea, but it is definitely at the forefront of oolongs today. At this stop on the tea tour, attendees learned about what oolong tea actually is, and tasted a variety of Taiwanese oolongs, including Bao Zhong, White Tip Bai Hao, and of course Tieguanyin,…

-

Free mystery tea (Tieguanyin)!

A friend stopped by the tea bar the other day and brought a bag of tea from China that a friend had given her. She didn’t know what it was, and she’d had it for five years, so she asked if I’d like to have it.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Mastodon (Opens in new window) Mastodon

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print