Blog Archives

Japan – Bancha to Matcha: Stop 4 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

We’re very excited to be working with resident artist Karin Solberg from the Red Lodge Clay Center, and we are featuring some of her matcha bowls in the store, and she came in to talk about them at this stop in the tour.

The teas we tasted were:

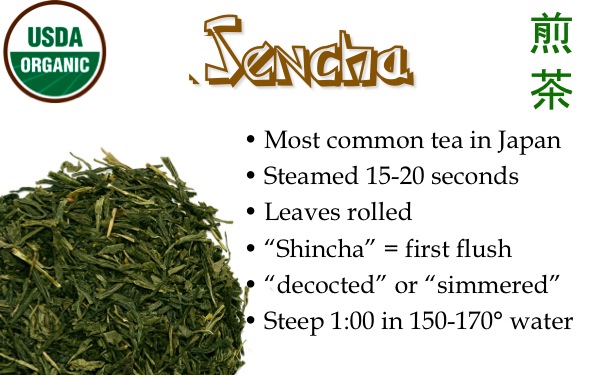

- Organic Sencha

- Gyokuro

- Organic Houjicha (roasted green tea)

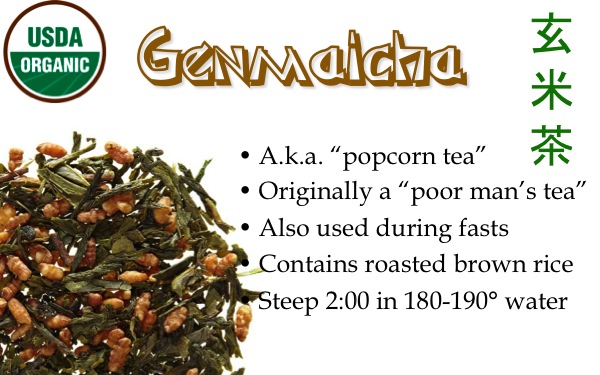

- Organic Genmaicha (toasted rice tea)

- Organic Matcha

- Kukicha (“twig tea”)

- Bancha (“coarse sencha”)

- Sencha (“decocted tea”)

- Gyokuro (“jade dew”)

Tea and caffeine part II: Exploding the myths

A misunderstood molecule

This article is the second of a three-part series.

Part I: What is caffeine?

Part II: Exploding the myths

Part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

It’s amazing. It seems like the more I learn about tea, the less I know — and the more I have to unlearn. Over the many years that I’ve been drinking and enjoying tea, I’ve picked up a lot of misconceptions. I’ve even been guilty of spreading a few of those. In the last couple of years, though, as I’ve been more actively studying tea, I’ve discovered the errors of my ways, and this article will serve both as an educational tool and a mea culpa for repeating things without doing my homework.

I already started the myth busting in the previous article with some discussion of decaffeination (Myth: decaf tea has no caffeine. Fact: decaf tea has had some of its caffeine removed). With no further ado, then, let’s continue the process by taking a look at a series of common myths and misconceptions about tea and caffeine, and the relevant facts for each.

You can decaffeinate tea at home with a short “wash”

I picked up this one in several books and numerous articles on the web. In its most common form, the myth says that if you add boiling water to your leaves, swish it around for a short time (most commonly 10 to 30 seconds) and then dump it, you’ve just removed most (claims range from half to 80% or more) of the caffeine.

Bruce Richardson debunked this in his article, Too Easy to be True: De-bunking the At-Home Decaffeination Myth, which appeared in the January 2009 Edition of Fresh Cup magazine. Working with a chemistry professor at Asbury College and one of his students, they determined that it took a 3-minute infusion to extract 46-70% of the caffeine from the tea leaves. You could do a 3-minute wash, I suppose, but you’d be extracting 46-70% of the flavor, too.

Kevin Gascoyne presented some of his research in a 2012 World Tea Expo seminar: A Step Toward Caffeine and Antioxidant Clarity. He used a batch of Long Jing Shi Feng (a green “Dragonwell” tea), which he steeped for varying amounts of time. He measured caffeine content of each infusion and graphed the results. At 30 seconds, a bit over 20% of the caffeine had been removed. By 3 minutes, it was around 42% (even lower than Richardson’s numbers). It was 8 minutes before 70% of the caffeine was extracted, and the graph pretty much flattened out there.

This process is roughly cumulative, so if you infuse your tea for 6 minutes, you’re getting about the same total caffeine as if you’d infused those same leaves 3 times, at 2 minutes per infusion. My favorite shu pu-erh may not have more caffeine than, say, your favorite sencha, but by the time I’ve finished off my 7th infusion — and you’ve infused your leaves once — I’ve probably consumed more caffeine than you have (although I’ve had 7 cups of tea and you’ve had 1).

Green tea has less caffeine than black tea

Pretty much every piece of research in the last decade has debunked this myth. And when I say “debunked,” I’m not saying that the opposite is true; I’m saying that different teas have different caffeine content, but the processing method has little to do with it.

For example, Kevin Gascoyne, in the seminar I mentioned above, presented a chart of the teas that he’d tested, ranked by caffeine content. Aside from the pu-erh teas clustering toward the center (we’ll look at why in a moment), the distribution of styles (white vs. green vs. oolong vs. black vs. pu-erh) was almost random. Even very similar teas had very different caffeine levels, like the Sencha Ashikubo with 48 mg of caffeine and the Sencha Isagawa with 12 mg.

As Gascoyne analyzed his data, he came to the conclusion that there’s a certain amount of caffeine in the tea leaves, and the processes of picking, crushing, steaming, pan-firing, rolling, oxidizing, fermenting, drying, and tearing neither create nor destroy caffeine (one exception to this, according to an article on RateTea, is that roasting a tea like houjicha can dramatically reduce caffeine). If a particular tea bush in Taiwan produces a very high-caffeine oolong tea, then that exact same bush would produce a very high-caffeine black or green tea.

The caffeine content depends on many things, including the varietal of bush, the type of soil, the fertilizer used (if any), the weather, the season when the leaves are picked, and maybe even the time of day. Richardson’s article says that adding nitrogen fertilizer can raise caffeine content by 10%. Gascoyne said he analyzed tea picked from the same plantation at different times of year and found dramatically different caffeine levels.

White tea has no caffeine (or very little)

This one is not only a bad generalization like the previous myth, but often completely backwards!

Another thing that affects caffeine extraction is the part of the plant you use. Caffeine is a natural insecticide. The caffeine tends to congregate in the newer growth, thus protecting the plant from bugs that might eat its tender shoots and young leaves. Richardson’s article described research results from Nigel Melican, the student doing the analysis. His caffeine percentage findings were:

Bud-6.3%

First leaf-4.6%

Second leaf- 3.6%

Third leaf-3.1%

Fourth leaf-2.7%

Leaf stalk-2.0%

Two leaves and a bud-4.2%

Since the finest white tea is often made from all buds or a bud-and-a-leaf, it will actually have significantly higher caffeine than a strong black tea made from the whole stalk or the 2nd-4th leaves.

When hydrating, you should avoid caffeinated beverages

According to Kyle Stewart and Neva Cochran in their seminar, Tea, Nutrition, and Health: Myths and Truths for the Layman, at World Tea Expo 2012, “studies show no effect on hydration with intakes up to 400 mg of caffeine/day or the equivalent of 8 cups of tea.”

The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine agreed. In their 2004 reference intakes for water, they state: “caffeinated beverages appear to contribute to the daily total water intake similar to that contributed by non-caffeinated beverages.”

In other words, if you want to drink six pints of water per day for health reasons, it’s perfectly fine to steep some tea leaves in that water before you drink it!

You shouldn’t drink tea with caffeine at night

Stewart and Cochran cited another study in their seminar which analyzed tea and sleep. They found that people unused to caffeine would experience longer times to fall asleep and lower sleep quality, as would people who consumed more than 400 mg of caffeine per day (around 8 cups of typical tea).

People who spread their consumption out through the day, maintaining caffeine in the system (cups at 9:00 am, 1:00 pm, 5:00 pm, and 11:00 pm) were able to sleep with little disruption.

But what if you have no tolerance for caffeine, or you need to maintain very low levels? In the third and final part of this series, we’ll explore some alternatives you might want to try.