Category Archives: Styles

Making traditional masala chai at home

Before we address the topic at hand, may I take a moment to get something off of my chest?

Today we are discussing a tea called masala chai. The word “masala” refers to a yummy blend of spices, often containing cardamom, ginger, and pepper. The word “chai” means “tea” in Hindi (and Urdu, and Russian, and Bulgarian, and Aramaic, and Swahili, and a variety of other languages). Therefore, when you refer to “chai tea,” you’re talking about “tea tea.” Although most Americans call masala chai just “chai,” they really should be calling it “masala” or “masala tea” if they don’t want to say “masala chai.”

We can thank the coffee industry for confusing our terminology a couple of decades ago, as they coined the phrase “chai latte” to differentiate masala chai (traditionally made with milk) from coffee lattes. Your other word of the week is “latte,” which just means “with milk” and has nothing whatsoever to do with coffee. Tea made with heated and frothed milk is a latte, too!

Thank you. I feel better now. On to the aforementioned topic at hand:

I would never presume to tell you the right way to make a cup of tea. As I’ve mentioned so many times before, there is no single right way to do it. In this post, however, I will talk about one of the traditional ways to make masala chai. In India, where this concoction (or decoction, if you prefer) originated, it is almost always made with milk and sugar.

In a coffee shop, masala chai (which they usually call a chai latte) is almost always made from a pre-sweetened concentrate. It’s quick and easy to make, and it tastes pretty good. But it doesn’t taste like authentic masala chai.

In a tea shop, masala chai is usually brewed fresh from a blend of black tea leaves and masala spices. If they add milk, it is usually poured in after the tea is brewed, unless the tea shop is specifically set up for lattes. You get that fresh-brewed taste, but somehow the spices don’t seem quite right to me (my tea bar does it differently, but that’s a topic for another post).

At home, you can make it the way they do in India.

The masala spices

First of all, the masala spice mix and the tea (chai) are usually purchased and stored separately. Just as many Americans have a family chili or soup or cookie recipe, many Indian families have their own masala recipe handed down through the generations. You can research and experiment to come up with your own, or go to your favorite tea shop and see if they have a blend for sale. Many tea shops (including mine) will sell you the masala spice mix they use in-house without the tea.

If you’re really serious about it, you’ll make each batch up fresh, grinding cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, pepper, ginger, and whatever other spices you use as needed. I know a few folks that do it that way, but not many. I’d recommend starting with a mix that you like.

The tea

In India, the tea leaf of choice is usually a rich black Indian tea like Assam. It’s brewed pretty strong so that you can taste the tea through all of the spice and milk and sweetener. That doesn’t mean you need to use an Assam, but it’s a good place to start.

The milk

Milk serves a definite purpose in masala chai. You can extract flavor from many spices much better in fats or oils than you can in water, as any chef will tell you. Steeping the spice blend in milk will result in a richer, more nuanced flavor than steeping it in water. In India, the milk of choice is typically water buffalo milk, which can be difficult to get hold of here in North America. The usual substitute is whole milk, although 1% or 2% is common with the more health-conscious crowd. Nonfat milk is rather pointless, as the fat is the main reason for using it.

The sweetener

Sugar. Some drink their masala chai unsweetened, but if there is sweetener, it will typically be sugar.

That said, when I’m making masala chai at home, I usually use honey or agave nectar.

The process

You’ll need a pan, a stove, and a strainer to do this. This is my recipe for making enough for you and a few friends. Adjust accordingly if you’re drinking it by yourself.

- Heat up a pint (16 oz) of milk in the pan, but do not bring to a boil!

- Add 1-1/2 tablespoons of masala spice mix and simmer for five minutes, stirring gently

- Bring a pint (16 oz) of water to a boil in a kettle or microwave

- Add the water to the pan along with 1-1/2 tablespoons of tea leaves

- Stir in 1 teaspoon of sugar or honey

- Allow to simmer for another five minutes, stirring occasionally

- Pour through strainer to remove leaves and spices, and serve immediately

Put out more sugar or other sweetener for your guests. That single teaspoon is a lot less than a traditionalist would use, but I prefer to let everyone choose their own level of sweetness.

For best results, enjoy with your favorite Indian foods. Masala chai does a wonderful job of cutting the spiciness of curries. You can also use your masala chai tea in your Indian cooking: see my post on Chai Rice.

NOTE: The resulting masala chai will not look like the latte in the picture above. To get that look, I frothed up some milk and placed the foam on the top of the cup, and then added a dash of cinnamon powder.

Tea blends you can’t put in a bag

Before I get to the subject of today’s blog post, I’d just like to get a little announcement out of the way. My last post was the 100th post to Tea With Gary. Yay! Celebration! Fireworks!

Okay, now on to tea blends.

Professionals developing tea blends have several goals in mind beyond just making something yummy. One absolute requirement is that it has to be simple for the consumer to make at home. And by simple, I mean the instructions have to read like this: “Put ____ teaspoons of leaves in ____ ounces of water at ____ degrees, and steep for ____ minutes.” If at all possible, “water at ____ degrees” should be replaced with “boiling water,” but sometimes that’s not practical.

When I’m having fun with tea blends at home (or in my case, at the tea bar), I’m often faced with a conundrum. I want to combine significantly different teas, but they require different steep times or water temperatures — or sometimes both. A perfect example of this is the oolong/pu-erh blend that I made the other day.

I like the particular oolong that I used (Iron Goddess of Mercy) steeped for about three minutes. I wanted to try blending it with a loose-leaf ripe pu-erh, but I really didn’t like the results. Even if I backed off on the amount of pu-erh, that three minutes is just too long for me. If I steeped the blend as long as I’d steep the pu-erh by itself (about a minute and a half), then the oolong flavor didn’t come through properly.

For such an obvious solution, it took me the better part of a day to come up with it. Here are my instructions for this lovely blend:

- Place 1-1/2 teaspoons of Iron Goddess in 16-ounce infuser (or teapot) filled with 200 degree water

- Steep for 1:30

- Add 2 teaspoons of shu pu-erh to infuser

- Continue steeping for another 1:30

- Pour tea into mug, filtering out leaves

- Enjoy

The alternative would be to brew the two teas separately and then combine them in the cup, but that ends up being much more complicated and messy, and dirties two infusers. On the other hand, that method allows you to use the leaves more than once — and both of these teas lend themselves to multiple infusions. It also takes some experimentation to make that system work.

A direct translation of that infusion method to multiple infusers would look like this:

- Place 1-1/2 teaspoons of Iron Goddess in infuser (or teapot) with 8 ounces of 200 degree water

- Steep for 3:00 and pour tea into 16-ounce mug, filtering out leaves

- Place 2 teaspoons of shu pu-erh in a second infuser (or teapot) with 8 ounces of 200 degree water

- Steep for 1:30 and add tea to mug from step 2, filtering out leaves

- Once both teas have been blended in the mug, stir briskly

- Enjoy

If you just do the math here, it would seem to be a completely equivalent brewing process, but it’s not. The results are quite different when you steep 1-1/2 teaspoons of oolong in 8 ounces of water or when you steep 1-1/2 teaspoons of oolong in 16 ounces of water. Making that second method produce the same results would require a good bit of finagling.

For me, though, this game isn’t about producing the perfect cup for resale. It’s about experimenting with flavors, doing things that Lipton can’t put in a bag, and coming up with something I like. There are some blends that have worked very well for me this way. There are others that have pretty much bombed every time.

Among the experiments I’ve considered successful are adding fresh raspberries to pouchong oolong, adding a dash of zinfandel (wine) to an aged wild shu pu-erh, and mixing a short-steeped green tea with a long-steeped white tea. Primary among the bombs is blending green and black tea. Regardless of steep time and style, I have yet to find a combination I find palatable.

Don’t be afraid to experiment. Don’t be afraid to blend things together that might make your tea absolutist friends gasp. Tea should be fun.

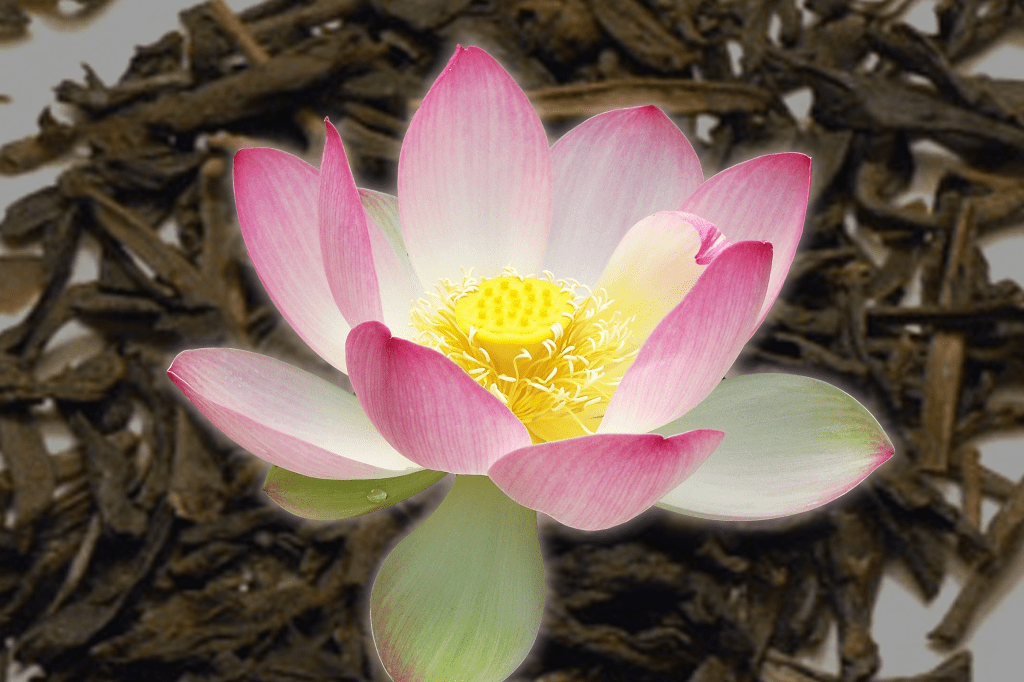

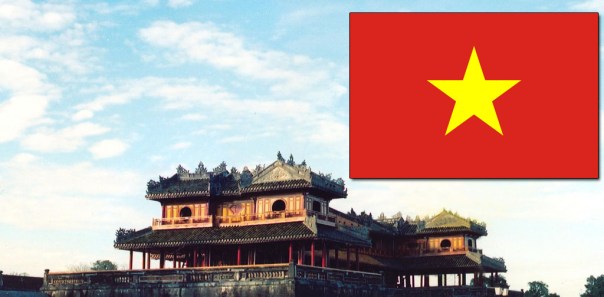

Vietnamese Lotus Tea

Although my tastes generally run to non-flavored tea, I have long enjoyed Chinese jasmine tea. Technically, it is scented rather than flavored, but either way you’re getting more than just the flavor and aroma of the tea. The producer starts with a good green tea, produces in the Chinese manner (pan-fired rather than steamed, as the Japanese do). They pick fresh jasmine blossoms and layer them in with the tea overnight. The scent from the jasmine infuses the tea, and in the morning they take the jasmine blossoms out and re-dry the tea to remove the moisture from the flowers. This process is typically repeated up to about six or seven times.

I speak here of the traditional production method. Cheap green tea can be made by simply spraying jasmine extract onto tea leaves.

At World Tea Expo this year, one of my goals was to expand my knowledge of tea from parts of the world other than the ones we most encounter in the U.S. (China, India, Japan, Kenya, and Sri Lanka) and to expand the tea selection in my tea bar. I made quite a few new discoveries, one of which was lotus blossom tea from Vietnam.

Vietnam?

If you walk into an average tea shop, you’re not likely to encounter much Vietnamese tea, if any at all. Vietnam, however, is the sixth-largest producer of tea in the world, with annual production approaching 200,000 tonnes — over double that of Japan, which has fallen to tenth place.

Green tea in Vietnam is produced as it is in China. The tradition of lotus blossom tea is similar to that of jasmine tea, but with a twist. Unlike a jasmine flower, a lotus blossom is a large bloom that seals up tightly like a tulip. By ancient Vietnamese tradition, lotus blossom tea is produced by filling fresh lotuses with green tea and binding the blossom together overnight. In the morning, the flower is opened and the highly-scented tea extracted. Today, the process is more likely to be like jasmine tea. Often, freshly-picked lotuses — or just the stamens of the flowers — are sealed up with the tea in an airtight container or baked with the tea.

Lotus tea, like jasmine tea, gets more aroma than flavor from the flower. Since lotus is much less delicate than jasmine, I settled on a pretty short brewing time of two minutes. When I raised the cup to my nose, the first thing to hit me was the smell of anise (licorice). I’m not a big licorice fan, so I was a bit put off, but I took another whiff. Beneath that strong anise is the vegetal aroma so common with Chinese green teas, but a bit earthier. The taste is very pleasant with a nice medium body to it.

The lotus tea I have came from the Thái Nguyên province in northeastern Vietnam. It is a mountainous area where a lot of Vietnam’s tea is grown.

I don’t know if it’s going to become one of the most popular teas in the tea bar, but it will certainly become one of our regular offerings. I’ve begun recommending it to people who want to try something a bit different, and reactions have been mostly either “wow!” or “meh.” If you like floral tea and you’re ready to move beyond the jasmine blossoms of China and the cherry blossoms of Japan, then I would definitely recommend trying this unique Vietnamese treat.

Champagne, Tequila, Darjeeling, and Dark Tea

If you make a carbonated white wine, it’s called a “sparkling wine,” unless you are producing it in the Champagne region of France. Then, and only then, should it be called Champagne. I say “should” because there are a number of countries that didn’t sign (or don’t honor) the treaties involved, but that’s a whole different blog post.

The same applies to beverages made from distilling blue agave cactus. If you are in the Mexican state of Jalisco, or designated portions of certain other states, you may call that beverage Tequila. Otherwise, you have made mezcal.

The theory behind these distinctions is not so much the strict corporate trademark enforcement that governs most usage of names in the U.S. It is more a question of terroir. If you were to take two cuttings from the same grape vine and plant one in Napa Valley, California and the other in the Rhine Valley of Germany, you would get different wines from the two vines. Terroir describes the effect that the soil, weather, drainage, and related geographical factors have on the resulting taste of the beverage, whether it be wine or tea.

Darjeeling tea is often called the Champagne of tea (this appellation is usually reserved for first flush Darjeeling tea, but we’ll ignore that distinction for the moment). This little factoid has little to do with the subject of the article, but does make for a marvelous segue from alcoholic beverages to teas, n’est pas?

Like Champagne and Tequila, Darjeeling refers not only to a particular style of tea, but to the origin of that tea: the Darjeeling district of West Bengal, India. Darjeeling tea is unique because of its terroir, but also because of the varietal of the tea plant that they use. Most tea grown in India comes from Camellia sinensis var assamica (the varietal native to India), but Darjeeling tea comes from Camellia sinensis var sinensis (the varietal native to China). Combining the terroir of West Bengal with the flavor of the Chinese tea plant produces the tea we’ve all come to know and love.

And, finally, we get to dark tea

Another geographically-named tea style is pu-erh (also spelled pu’er or puer), named for the town in the Yunnan province of China where the style originated. Only recently has the tea industry really started using the more generic name of “dark tea” to refer to fermented (as opposed to oxidized) teas.

There are two ways to make pu-erh: sheng and shu (also spelled shou).

SHENG (a.k.a. raw or green pu-erh) is the more prized by collectors. The tea is stored in a slightly damp humidity-controlled environment and allowed to slowly ferment. It’s generally not considered ready to drink for years after being picked. Shengs have the same vegetal flavors and aromas as a good Chinese green tea, but with very complex earthy undertones.

SHU (a.k.a. ripe or cooked or black pu-erh) gets a bacterial “kick-start” to the fermentation process, so it’s ready to drink within a matter of months instead of years. Shu pu-erh requires very little steeping time (I’ve spoken to producers that recommend as little as ten seconds), and many pu-erh drinkers start with a “wash,” where you add boiling water, swirl for a few seconds, and pour it off before doing a “real” steeping. Shu pu-er tends to be extremely earthy, with a “composty” undertone. The flavor profile is even richer and deeper than a strong black tea (often reminiscent of a good Keemun), but with very little astringency.

There are several common shapes of pu-erh cakes, including rectangular bricks, bird-nest shapes (“tuo cha”), and flat disks (“beeng cha”).

The standard size for a beeng cha (like the one pictured above, which I wrote more about) is 357 grams, although they can be found in smaller sizes as well. I’ve found several suppliers for 100g beeng chas lately, which is a more affordable alternative for someone new to dark teas or someone sampling a new variety.

Tuo chas, on the other hand, are available in a wide variety of sizes usually centered around 80-120g. Mini tuo chas have become quite common. Each is a single serving of tea, roughly 5g.

Bricks can be found in a variety of sizes as well.

Something new (to me, anyway) is the log-shaped dark tea. My wife, Kathy, and I found these at the World Tea Expo (the big annual industry trade show for tea people) a couple of weeks ago. The ones we purchased for our tea bar are logs about 3.625 kilos (8 pounds), 25 inches long by 5 inches in diameter. We’re selling a single log in its bamboo wrapping with a canvas carry tote for $99.99, but most people will be more interested in slices taken from the log.

In the picture below, Kathy and I are posing with what the tea grower calls the world’s largest log of dark tea. If it puts the size of that tea log in perspective, I am 6’5″ tall (195 cm) not counting the hat and boots. Not having a spare thousand dollars laying around, we didn’t buy that one!

Argentina and Yerba Maté: Stop 8 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

While Europe was getting hooked on coffee and Asia was drinking tea, the people of Argentina and Paraguay were enjoying their own indigenous source of caffeine: yerba maté.

Yerba maté comes from a plant called Ilex paraguariensis, a species of holly which contains caffeine and other xanthines. Maté is a traditional beverage throughout South America, typically served hot (well, “warm” by American standards) and shared among friends from a gourd and bombilla (metal or cane straw).

The matés we tasted were:

- Traditional green yerba maté (organic)

- Roasted yerba maté

- Montana huckleberry maté

- Carnival maté

- Eye of the Storm (our house blend minty maté)

Although when it comes to caffeinated drinks, Argentina is mostly known for its yerba maté, the country is the world’s 9th largest producer of tea, with an annual production of about 60,000 tons. Most of that tea is used in blends and iced teas, and it’s pretty rare to find an Argentinian tea on the menu at a tea bar.

In land area, Argentina is the world’s 8th largest country, covering over a million square miles. Their population is just over 40 million, and the main language is Spanish.

Yerba Maté

The word maté actually means “gourd,” a reference to the vessel traditionally used when drinking yerba maté in most of South America. In Paraguay, on the other hand, they often drink their maté cold (they call it tereré) from a guampa, a drinking vessel made from an ox horn.

The total world production of yerba maté is about 500,000 tons, of which about 290,000 tons comes from Argentina: almost five times their annual tea production. The rest is almost all grown in Brazil and Paraguay. This makes it about a $1.4 billion market (in U.S. dollars) — much bigger than the rooibos market we talked about last week. The majority of the maté is consumed in South America, with the largest outside buyer being Syria.

Maté is usually produced like a green tea, with minimal oxidation. The gourd is packed about half full with leaves in an elaborate ritual, and then filled the rest of the way with water at about 150 degrees F. Argentinian children enjoy maté, too, usually prepared with milk.

In the U.S., maté is more often prepared like tea, by steeping in hot or boiling water. A bit of sugar can help to cut the bitterness caused by the hotter water.

We tasted both a plain maté and one of our house blends with peppermint and spearmint added (that one is yummy iced!).

Roasted Maté

It is becoming increasingly popular to roast the maté, producing a drink that is darker and richer. The taste of roasted maté is often compared to coffee or chicory. We tasted a plain roasted maté plus two flavored ones: a “carnival” maté with caramel and Spanish safflower, and a Montana huckleberry maté.

Caffeine and Maté

It was long thought that maté contained a chemical called mateine, similar to caffeine and a member of the xanthine family. Recent research has shown that mateine actually is caffeine, and it just showed up differently in lab tests because of other compounds present in the maté.

Yerba maté contains three different xanthines: caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline. The total caffeine content is higher than a typical cup of tea, but less than a strong coffee. The way the maté is prepared has a great effect on the caffeine content: the temperature of the water, the steep time, and the amount of leaf used all interact to influence how much caffeine is extracted from the leaves into the drink.

When I have some more time, I’ll write a post detailing and illustrating the maté ceremony.

This was the eighth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from February.

The Rooibos of South Africa: Stop 7 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

If you’re looking for a drink with all the health benefits of tea, a similarly great taste, but no caffeine, look to South Africa! Rooibos is made from the South African red bush (Aspalathus linearis). Using rooibos instead of tea is a great way to enjoy a caffeine-free hot (or iced) drink without using any chemical decaffeination process. Rooibos is full of antioxidants, Vitamins C and E, iron, zinc, potassium, and calcium. It is naturally sweet without adding sugar.

Rooibos grows only in the Western Cape of South Africa, and a similar plant called honeybush (the Cyclopia plant) grows in the Eastern Cape. Its flowers smell of honey, hence the name. The taste of honeybush is similar to rooibos, though perhaps a bit sweeter. Like rooibos, honeybush is naturally free of caffeine and tannins; perfect for a late-evening drink.

The teas we tasted were:

- Red rooibos (organic)

- Green rooibos (organic)

- Honeybush (organic)

- Jamaica red rooibos (organic, fair trade)

- Bluebeary relaxation (organic, fair trade)

- Iced rooibos

- Cape Town Fog (a vanilla rooibos latte!)

South Africa, as the name implies, sits at the very southern tip of the African continent. It completely surrounds a small country called Lesotho. South Africa covers 471,443 square miles (about three times the size of Montana) and has a population of 51,770,000 (a bit more than Spain). Despite wide open spaces in the middle of the country, the large cities make it overall densely populated.

The country has the largest economy in Africa, yet about 1/4 of the population is unemployed and living on the equivalent of US $1.25 per day.

Red rooibos

Rooibos isn’t a huge part of the South African economy. It does, however, employ about 5,000 people and generates a total annual revenue of around US $70 million, which is nothing to sneeze at. The plant is native to South Africa’s Western Cape, and the country produces about 24,000,000 pounds of rooibos per year.

The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans. In the U.S., it’s pronounced many different ways but most often some variant of ROY-boss or ROO-ee-bose.

I’ve written quite a bit about red rooibos in several posts — and about the copyright issues — so I won’t repeat it all here. Rooibos is also great as an ingredient in cooking: see my African Rooibos Hummus recipe for an example.

Green rooibos

Green rooibos isn’t oxidized, so it has a flavor profile closer to a green tea than a black tea. Again, I’ve written a lot about it, so I’ll just link to the old post.

Honeybush

Honeybush isn’t one single species of plant like rooibos. The name applies to a couple of dozen species of plants in the Cyclopia genus, of which four or five are used widely to make herbal teas. Honeybush grows primarily in Africa’s Eastern Cape, and isn’t nearly as well-known as rooibos.

It got its name from its honey-like aroma, but it also has a sweeter flavor than rooibos. It can be steeped a long time without bitterness, but I generally prefer about three minutes of steep time in boiling water.

Jamaica Red Rooibos

I decided to bring out a couple of flavored rooibos blends for the tasting as well. The first is Jamaica Red Rooibos, a Rishi blend. It has an extremely complex melange of flavors and aromas, and is not only a good drink, but fun to cook with as well (see my “Spicing up couscous” post).

Jamaica Red Rooibos is named for the Jamaica flower, a variety of hibiscus. The extensive ingredient list includes rooibos, hibiscus, schizandra berries, lemongrass, rosehips, licorice root, orange peel, passion fruit & mango flavor, essential orange, tangerine & clove oils

BlueBeary Relaxation

BlueBeary Relaxation one of the blends in our Yellowstone Wildlife Sanctuary fundraiser series (the spelling “BlueBeary” comes from the name of one of the bears at the Sanctuary). It’s an intensely blueberry experience that’s become a bedtime favorite of mine. It’s like drinking a blueberry muffin!

Iced rooibos

To make a really good cup of iced rooibos, prepare the hot infusion with about double the leaf you’d use normally, because pouring it over the ice will dilute it. Both green and red rooibos make great iced tea. I prefer both styles unadulterated, but many people drink iced red rooibos with sugar or honey.

Cape Town Fog

This South African take on the “London Fog” is a great caffeine-free latte. To prepare it, you’ll want to preheat the milk almost to boiling. If you have a frother of some kind, use it — aerating the milk improves the taste. Steep the red rooibos good and strong, and add a bit of vanilla syrup or extract. We use an aged vanilla extract for ours. Mix it all up, put a dab of foam on top if you frothed the milk, and optionally top with a light shake of cinnamon.

This was the seventh stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from February.

The Oolongs of Taiwan: Stop 6 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Taiwan may not have originated oolong tea, but it is definitely at the forefront of oolongs today. At this stop on the tea tour, attendees learned about what oolong tea actually is, and tasted a variety of Taiwanese oolongs, including Bao Zhong, White Tip Bai Hao, and of course Tieguanyin, better known as “Iron Goddess of Mercy.” We’ll also talk a bit about the history of Formosa tea (Taiwan was called Formosa until the 1940s).

For comparison, we also tasted a couple of Chinese oolongs.

The teas we tasted were:

- Bao Zhong (Pouchong) – Taiwan

- White Tip Bai Hao – Taiwan

- Tieguanyin (Iron Goddess of Mercy) – Taiwan

- Wuyi (Shui Xian) – China

- Qilan (Dark) – China

- Boba (“bubble”) Tea – Taiwan

Officially, Taiwan is known as the Republic of China (ROC). It is an island off the coast of mainland China, which is officially known as the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The PRC lays claim to Taiwan, but the ROC has declared its independence and established its own government, currency, and economy. The island, formerly known as Formosa, is 13,978 square miles — only about a tenth the size of the state of Montana. It’s population, however, is about 23,315,000, which is significantly more than the state of Texas.

A variety of tea styles is produced in Taiwan, but their specialty is oolong. About 20% of the world’s oolong tea comes from this small island.

There have been wild tea plants on Taiwan for a long time. They were first reported to the Western world in a report in 1685. Chinese tea plants were brought out to Taiwan by Ke Chao in the late 18th century, and a Scotsman named John Dodd established a tea export business in 1869. Tea soon became Taiwan’s major export, and the Tea Research Institute of Taiwan was formed in 1926.

Oolong, which means “black dragon” in Chinese, is the most complex of tea styles to produce. Oolongs are generally not crushed or torn, and are only partially oxidized (not fermented), unlike green tea, which isn’t oxidized at all, and black tea, which is fully or almost-fully oxidized.

Generally, we tailor the steep time and water temperature to each individual tea in our tastings, but tonight we wanted to give everyone a solid basis for comparison, so we prepared all of the oolongs in 195-200 degree (F) water and steeped them for two minutes.

Pouchong

Pouchong is often spelled as “Bao Zhong” to more accurately reflect the way it is pronounced. It’s a very lightly oxidized oolong tea that appeals well to green tea lovers. Because of its mild taste and aroma, many flavored oolongs use pouchong as their base.

White Tip Bai Hao

Here’s a tea with many names, including Bai Hao in the east and Oriental Beauty in the west. In the beginning, it was known as “bragger’s tea” because of the origin story (one of the stories that will appear in my new book, by the way), where a farmer went ahead and used leaves that had been chewed up by insects and discovered that the flavor was so wonderfully enhanced that he got twice his normal price at market.

Tieguanyin (Iron Goddess of Mercy)

This style originated in China, but has become a staple of Taiwanese oolong as well. I’ve written about it before. Even with 120 different teas to choose from in my tea bar, it’s rare for me to go more than a couple of days without drinking a few cups of Tieguanyin. It’s generally good for at least 5-7 infusions, and it’s a great everyday tea.

Wuyi Oolong

We then moved to the birthplace of oolong tea: the Wuyi mountains in the Fujian province of China. This tea is highly oxidized and then roasted to give a very full-flavored cup. We tasted it on the first stop (China) of our World Tea Tasting Tour, making this the first tea that’s been in two different tastings.

Qilan Oolong

Staying in that same area, we moved on to an even more oxidized and roasted dark oolong. Qilan (“profound orchid”) is actually a darker and more flavorful tea than many of my favorite black teas, like Golden Yunnan, Royal Golden Safari, and first-flush Darjeeling (all described in previous tasting notes).

Boba Tea

The most recent export from Taiwan is an iced drink they call “boba milk tea,” usually served as “bubble tea” in the United States. It has taken many urban areas here by storm, especially in the Pacific Northwest. Unfortunately, the way most of the mainstream purveyors prepare it, there’s no tea in bubble tea — they use snowcone syrups or similar super-sweet flavorings.

We prepare ours by steeping a strong cup of tea (tonight’s tasting used a mango-flavored tieguanyin as the base). In a cocktail shaker we add ice, simple syrup (sugar water), and a bit of milk. After shaking that into a froth, we pour it over fresh-made tapioca pearls.

This was the sixth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from February.

Oolong-related articles on Tea With Gary

-

The Oolongs of Taiwan: Stop 6 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

Taiwan may not have originated oolong tea, but it is definitely at the forefront of oolongs today. At this stop on the tea tour, attendees learned about what oolong tea actually is, and tasted a variety of Taiwanese oolongs, including Bao Zhong, White Tip Bai Hao, and of course Tieguanyin,…

Deepest Africa – The Tea of Kenya: Stop 5 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

When you think of tea, Africa probably isn’t the first place to pop into your mind, but Kenya is the largest exporter of tea in the world. Tea has revitalized their economy, and tea lovers everywhere became winners. Red Lodge Books & Tea works with family owned plantations in Kenya, and was the first tea bar in the United States to serve Kenya’s unique purple tea.

Kenya is known for its black tea, but with their expanding tea economy, the country has expanded into other styles. We tasted some green and white tea from Kenya, along with traditional estate-grown Kenyan black teas and with some fun and different tea you just can’t get anywhere else.

The teas we tasted were:

- White Whisper

- Rift Valley Green Tea

- Golden Safari (black)

- Lelsa Estate FBOP (black)

- Royal Tajiri (black)

- Purple Tea

A quick bit of background on Kenyan tea before we go any farther. As I mentioned earlier, Kenya is the largest exporter of tea in the world, and the third largest producer (after China and India). Largely because of the population difference, Kenya doesn’t consume as much of its product as China and India do. Kenya produces about 345,000 tons of tea per year, but consumes only about 32,000 tons of that. About 9.6% of the world’s total tea production comes from Kenya.

Those are fascinating statistics, but let’s put some human faces on them. When I wrote my first blog post about purple tea in 2011, I was contacted shortly afterwards by a Kenyan woman by the name of Joy W’Njuguna. I had the pleasure of meeting her in 2012 at the World Tea Expo, as you can see in the picture below. She’s not actually that short — it’s just that I’m six-foot-five and I’m wearing a cowboy hat, so she does look like a tiny little thing.

CAUTION: Before doing business with Royal Tea of Kenya or Joy W’Njuguna, please read my post from May 2014. There are at least a dozen companies (mine included) that report paying for tea and never receiving it!

I’ve learned a lot from Joy about Kenya and its tea industry. One telling tidbit is that about half of Kenya’s tea is produced by corporate farms, and the other half by independent growers. I have a soft spot in my heart for the independents, since I own a (very) independent bookstore and tea bar. Joy, in addition to representing her own family business, is involved in a collaborative export business that represents a coalition of independent family farms in Kenya. The big producers there are focused on producing very high volumes of CTC (Crush, Tear, and Curl) tea that ends up in grocery store teabags. The independent growers are focused instead on producing high-quality handmade tea that will catch the attention of the rest of the world.

I like being able to put a face to the products I buy. I like being able to show my customers a picture and say, “See these people? These people hand-picked the tea you’re drinking. Not machines. We know where the tea came from and we know what we’re buying.”

Well, that’s probably enough of a soapbox for the day — or maybe even the month. Let’s move on to the teas that we tasted. If you’re like most of my customers, you didn’t even know Kenya produced a white tea. Heck, until about a year and a half ago, I didn’t know either. So let’s start there:

White Whisper

Silver Needle is one of the flagship teas of China. White Whisper is not a clone, but a Kenyan tea made with the same process. The vast differences in terroir make show from the first sniff. It’s richer and earthier than Silver Needle. Even at the 5:00 steep time we used, it’s less delicate. Personally, though, I love the complexity of this tea. Just pay close attention to that water temperature. You pour boiling water over these leaves and you’re going to ruin it.

Rift Valley Green Tea

The first time I tried this green tea, I wasn’t really impressed. Since it’s a pan-fired tea, I followed the general guidelines for Chinese greens and steeped it for three minutes. Next pass, I read the tasting notes from Royal Tea of Kenya, which recommend a thirty-second steep. Really? Thirty seconds? Yep. That’s all this tea needs.

I love the fact that this tea comes from the slopes of Mount Kenya. Some of my best memories of my trip to Kenya when I was in high school center around that area and the day and night we spent at the Mount Kenya Safari Club. What a wonderful place!

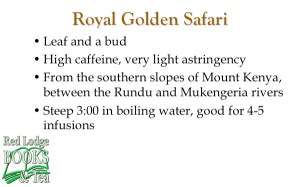

Royal Golden Safari

I’ve written about this tea before. It’s one of my favorite black teas. In this session, as in most of my tastings, I got raised eyebrows from people when I poured this and told them it was a black tea. It brews up pale red with just a touch of astringency and appeals to many oolong drinkers. Unlike most black teas, I regularly get four or five infusions out of Golden Safari.

Lelsa Estate FBOP

Next, we moved on to a much more traditional Kenyan black. This FBOP is one of the ingredients I use in Gary’s Kilty Pleasure (my Scottish breakfast blend). The estate in Kericho participates in the Ethical Tea Partnership program, which I appreciate, and the tea has a deep red color and characteristic Kenyan “jammy” notes. The maltiness blends well with Assam tea, and those who take their tea English-style will appreciate how well it takes milk.

Royal Tajiri

“Tajiri” is the Swahili word for “rich,” and this tea lives up to its name. The finely broken leaves mean an intense extraction. If you’re a black tea lover, this one will give you everything you’re looking for — assertive astringency, deep red (almost black) color, and a very complex flavor profile.

Royal Purple Tea

I’ve written so much about purple tea on this blog (here, here, and here) that I’ll skip the background data — although the picture on that slide is new: the tea on the left is a traditional Camellia sinensis, and the one on the right is the purple tea varietal TRFK306/1. The molecular structure in the background of the slide is the anthocyanin. I didn’t have my shipment of handcrafted purple tea yet (and the sample didn’t last long!), so we were unable to compare the orthodox to the handcrafted. I will put up separate tasting notes on that when my main shipment arrives.

I will note that we brewed the orthodox purple tea for this tasting with 170 degree (F) water instead of boiling, as I’ve done in the past. The cooler water brought out more of the complex undertones of the tea and backed the astringency down, making it more to my liking. We tasted this side by side with and without milk. If you haven’t had this tea with milk before, add a bit just to see the fascinating lavender color that the tea turns!

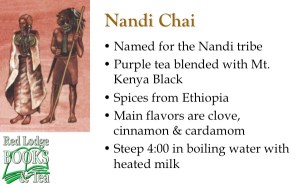

Nandi Chai

I confess. I was bummed that we didn’t get our handcrafted purple tea in time for this event. I kind of unloaded on Joy about it, and she was good enough to find me something else fascinating and unique for this event: an African chai. The tea (a blend of purple and traditional black) is from Kenya and the spices are all from Ethiopia.

We closed the tasting with this unique chai, and it went over very well. Instead of taking up half of this post talking about it, I’m going to dedicate a whole blog post to Nandi chai in the near future.

This was the fifth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from last month.

Kenyan Tea in the News

For some reason, there seems to be a lot going in in the world of Kenyan tea this month!

Kenya is the world’s largest exporter of tea. Not the largest producer, for they consume less than a tenth of the 345,000 tons of tea they produce each year — as opposed to China, which produces about 1.25 million tons, but consumes a staggering 1.06 million tons of it.

The fifth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour was the Tea of Kenya, which we held last week. I’ll be posting notes from the class and tasting shortly.

One of the things I’m most excited about is a new development in purple tea. The orthodox purple tea that I first wrote about in 2011 has a great story and many benefits. Tastewise, though, it is more astringent than I usually prefer, since I typically don’t take milk in my straight black tea. In other words, it’s just not my cup of tea (I’m allowed to make that pun once a year — it’s in my contract). This year, however, I got a sample of a new handcrafted purple tea from Kenya in February. Ambrosia. Absolutely wonderful stuff. I have a kilo on the way, and I’ll write up some decent tasting notes once it arrives.

For our tea tasting, they sent us a marvelous new chai (An African chai. Who’d have thunk it?) called Nandi Chai, after the Nandi peoples of Kenya. The tea is a blend of Kenyan black and purple varieties, and all of the spices are Ethiopian. I’ll be writing more on that later.

In other news, the Kenyan tea industry is trying to lower its costs and carbon footprint. An article in Tea News Direct says that four factories managed by the Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) are going green through the “Gura project,” which will build a hydroelectric plant on the nearby Gura river. The factories will receive carbon credits from the Clean Development Mechanism, which is part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

To end on a lighter note, there’s a post on the English Tea Store blog today that included a picture of what they called the ugliest teapot in the world (picture below). I honestly can’t decide whether it’s the ugliest or the most awesome. Had I spotted one when I visited Kenya decades ago, I would have almost certainly purchased it.