Blog Archives

Deepest Africa – The Tea of Kenya: Stop 5 on the World Tea Tasting Tour

When you think of tea, Africa probably isn’t the first place to pop into your mind, but Kenya is the largest exporter of tea in the world. Tea has revitalized their economy, and tea lovers everywhere became winners. Red Lodge Books & Tea works with family owned plantations in Kenya, and was the first tea bar in the United States to serve Kenya’s unique purple tea.

Kenya is known for its black tea, but with their expanding tea economy, the country has expanded into other styles. We tasted some green and white tea from Kenya, along with traditional estate-grown Kenyan black teas and with some fun and different tea you just can’t get anywhere else.

The teas we tasted were:

- White Whisper

- Rift Valley Green Tea

- Golden Safari (black)

- Lelsa Estate FBOP (black)

- Royal Tajiri (black)

- Purple Tea

A quick bit of background on Kenyan tea before we go any farther. As I mentioned earlier, Kenya is the largest exporter of tea in the world, and the third largest producer (after China and India). Largely because of the population difference, Kenya doesn’t consume as much of its product as China and India do. Kenya produces about 345,000 tons of tea per year, but consumes only about 32,000 tons of that. About 9.6% of the world’s total tea production comes from Kenya.

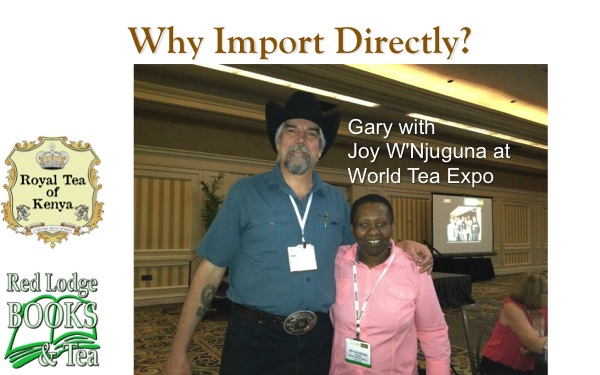

Those are fascinating statistics, but let’s put some human faces on them. When I wrote my first blog post about purple tea in 2011, I was contacted shortly afterwards by a Kenyan woman by the name of Joy W’Njuguna. I had the pleasure of meeting her in 2012 at the World Tea Expo, as you can see in the picture below. She’s not actually that short — it’s just that I’m six-foot-five and I’m wearing a cowboy hat, so she does look like a tiny little thing.

CAUTION: Before doing business with Royal Tea of Kenya or Joy W’Njuguna, please read my post from May 2014. There are at least a dozen companies (mine included) that report paying for tea and never receiving it!

I’ve learned a lot from Joy about Kenya and its tea industry. One telling tidbit is that about half of Kenya’s tea is produced by corporate farms, and the other half by independent growers. I have a soft spot in my heart for the independents, since I own a (very) independent bookstore and tea bar. Joy, in addition to representing her own family business, is involved in a collaborative export business that represents a coalition of independent family farms in Kenya. The big producers there are focused on producing very high volumes of CTC (Crush, Tear, and Curl) tea that ends up in grocery store teabags. The independent growers are focused instead on producing high-quality handmade tea that will catch the attention of the rest of the world.

I like being able to put a face to the products I buy. I like being able to show my customers a picture and say, “See these people? These people hand-picked the tea you’re drinking. Not machines. We know where the tea came from and we know what we’re buying.”

Well, that’s probably enough of a soapbox for the day — or maybe even the month. Let’s move on to the teas that we tasted. If you’re like most of my customers, you didn’t even know Kenya produced a white tea. Heck, until about a year and a half ago, I didn’t know either. So let’s start there:

White Whisper

Silver Needle is one of the flagship teas of China. White Whisper is not a clone, but a Kenyan tea made with the same process. The vast differences in terroir make show from the first sniff. It’s richer and earthier than Silver Needle. Even at the 5:00 steep time we used, it’s less delicate. Personally, though, I love the complexity of this tea. Just pay close attention to that water temperature. You pour boiling water over these leaves and you’re going to ruin it.

Rift Valley Green Tea

The first time I tried this green tea, I wasn’t really impressed. Since it’s a pan-fired tea, I followed the general guidelines for Chinese greens and steeped it for three minutes. Next pass, I read the tasting notes from Royal Tea of Kenya, which recommend a thirty-second steep. Really? Thirty seconds? Yep. That’s all this tea needs.

I love the fact that this tea comes from the slopes of Mount Kenya. Some of my best memories of my trip to Kenya when I was in high school center around that area and the day and night we spent at the Mount Kenya Safari Club. What a wonderful place!

Royal Golden Safari

I’ve written about this tea before. It’s one of my favorite black teas. In this session, as in most of my tastings, I got raised eyebrows from people when I poured this and told them it was a black tea. It brews up pale red with just a touch of astringency and appeals to many oolong drinkers. Unlike most black teas, I regularly get four or five infusions out of Golden Safari.

Lelsa Estate FBOP

Next, we moved on to a much more traditional Kenyan black. This FBOP is one of the ingredients I use in Gary’s Kilty Pleasure (my Scottish breakfast blend). The estate in Kericho participates in the Ethical Tea Partnership program, which I appreciate, and the tea has a deep red color and characteristic Kenyan “jammy” notes. The maltiness blends well with Assam tea, and those who take their tea English-style will appreciate how well it takes milk.

Royal Tajiri

“Tajiri” is the Swahili word for “rich,” and this tea lives up to its name. The finely broken leaves mean an intense extraction. If you’re a black tea lover, this one will give you everything you’re looking for — assertive astringency, deep red (almost black) color, and a very complex flavor profile.

Royal Purple Tea

I’ve written so much about purple tea on this blog (here, here, and here) that I’ll skip the background data — although the picture on that slide is new: the tea on the left is a traditional Camellia sinensis, and the one on the right is the purple tea varietal TRFK306/1. The molecular structure in the background of the slide is the anthocyanin. I didn’t have my shipment of handcrafted purple tea yet (and the sample didn’t last long!), so we were unable to compare the orthodox to the handcrafted. I will put up separate tasting notes on that when my main shipment arrives.

I will note that we brewed the orthodox purple tea for this tasting with 170 degree (F) water instead of boiling, as I’ve done in the past. The cooler water brought out more of the complex undertones of the tea and backed the astringency down, making it more to my liking. We tasted this side by side with and without milk. If you haven’t had this tea with milk before, add a bit just to see the fascinating lavender color that the tea turns!

Nandi Chai

I confess. I was bummed that we didn’t get our handcrafted purple tea in time for this event. I kind of unloaded on Joy about it, and she was good enough to find me something else fascinating and unique for this event: an African chai. The tea (a blend of purple and traditional black) is from Kenya and the spices are all from Ethiopia.

We closed the tasting with this unique chai, and it went over very well. Instead of taking up half of this post talking about it, I’m going to dedicate a whole blog post to Nandi chai in the near future.

This was the fifth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour, in which we explore the tea of China, India, Japan, Taiwan, England, South Africa, Kenya, and Argentina. Each class costs $5.00, which includes the tea tasting itself and a $5.00 off coupon that can be used that night for any tea, teaware, or tea-related books that we sell.

For a full schedule of the tea tour, see my introductory post from last month.

Kenyan Tea in the News

For some reason, there seems to be a lot going in in the world of Kenyan tea this month!

Kenya is the world’s largest exporter of tea. Not the largest producer, for they consume less than a tenth of the 345,000 tons of tea they produce each year — as opposed to China, which produces about 1.25 million tons, but consumes a staggering 1.06 million tons of it.

The fifth stop on our World Tea Tasting Tour was the Tea of Kenya, which we held last week. I’ll be posting notes from the class and tasting shortly.

One of the things I’m most excited about is a new development in purple tea. The orthodox purple tea that I first wrote about in 2011 has a great story and many benefits. Tastewise, though, it is more astringent than I usually prefer, since I typically don’t take milk in my straight black tea. In other words, it’s just not my cup of tea (I’m allowed to make that pun once a year — it’s in my contract). This year, however, I got a sample of a new handcrafted purple tea from Kenya in February. Ambrosia. Absolutely wonderful stuff. I have a kilo on the way, and I’ll write up some decent tasting notes once it arrives.

For our tea tasting, they sent us a marvelous new chai (An African chai. Who’d have thunk it?) called Nandi Chai, after the Nandi peoples of Kenya. The tea is a blend of Kenyan black and purple varieties, and all of the spices are Ethiopian. I’ll be writing more on that later.

In other news, the Kenyan tea industry is trying to lower its costs and carbon footprint. An article in Tea News Direct says that four factories managed by the Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) are going green through the “Gura project,” which will build a hydroelectric plant on the nearby Gura river. The factories will receive carbon credits from the Clean Development Mechanism, which is part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

To end on a lighter note, there’s a post on the English Tea Store blog today that included a picture of what they called the ugliest teapot in the world (picture below). I honestly can’t decide whether it’s the ugliest or the most awesome. Had I spotted one when I visited Kenya decades ago, I would have almost certainly purchased it.

Far Too Good For Ordinary People

Part of the fun of the tea business is the names. The names of the teas themselves are wonderful — from classics like Iron Goddess of Mercy to house blends like Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey — but the industry terminology is fun as well. Let’s take the “orange pekoe” grading system used for black teas from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and India.

Part of the fun of the tea business is the names. The names of the teas themselves are wonderful — from classics like Iron Goddess of Mercy to house blends like Mr. Excellent’s Post-Apocalyptic Earl Grey — but the industry terminology is fun as well. Let’s take the “orange pekoe” grading system used for black teas from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and India.

I can’t count the number of times someone has come into the tea bar telling me they like flavored teas. “You know, something like that Orange Pekoe stuff.”

“Actually,” I have to explain, “that’s not a style of tea, but a grade. And it has no flavorings at all. Nope. No orange in it.”

What I generally don’t go on to explain is how that whole pekoe grading system works. Let’s start with the words “orange” and “pekoe.” A pekoe is a tea bud, the unopened leaf at the very tip of a branch. A pekoe tea, then, would contain the buds and smallest leaves adjacent to the buds. To further confuse matters, the word “pekoe” in grading tea doesn’t mean quite the same thing as it means when speaking of tea buds. We’ll get to that in a moment.

“Orange,” as I mentioned above, has nothing to do with fruit. What it does actually mean is open to debate. It could refer to the color of the oxidized leaves. It could refer to the color of the brewed tea. It could refer to the Dutch royal family (the House of Orange). All that really matters is that in tea grading, any whole-leaf black tea qualifies as an Orange Pekoe.

So what about all those other letters? The joke in the tea business is that FTGFOP stands for “Far Too Good For Ordinary People.” In reality, it stands for “Fine (or Finest) Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe.” Referring to a grade of tea as the “finest” isn’t good enough, of course, so there are actually several grades above that. Here are the basic grades:

- OP (Orange Pekoe): A whole-leaf black tea.

- FOP (Flowery Orange Pekoe): Long leaves with some tips (pekoes).

- GFOP (Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): An FOP with more tips.

- TGFOP (Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): A GFOP with a whole lot of tips.

- FTGFOP (Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): Traditionally the highest-quality grade of black tea.

- SFTGFOP (Special Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe): Sorry, we needed one more grade.

For the true connoisseur, a grading system can never have fine enough gradations, so you can also elevate each of these grades another half-point by adding the number “1” after it. Thus, despite the industry joke, there are three grades of tea better than FTGFOP (FTGFOP-1, SFTGFOP, and SFTGFOP-1).

Let me reinforce an important point here: this grading system is used only for black teas, and only in a few countries. China, for example, rarely grades its teas using this system, although Kenya is doing more of it as their teas increase in quality.

Are there lower grades?

I thought you’d never ask.

The majority of tea consumed in the U.S. and U.K. is in teabags. In a traditional teabag, there’s little room for the hot water to circulate or the leaves to expand as they absorb water. The solution? Break those leaves into smaller pieces. That exposes more of the surface area of the leaf to water and allows more tea (by weight) to fit into a smaller area.

OP-grade teas use whole leaves. There is a series of grades below OP that include the letter B for “Broken.” BOP (Broken Orange Pekoe), FBOP, GBOP, and so on. There are also a couple of broken grades below BOP, including BP (Broken Pekoe) and BT (Broken Tea).

So that’s what’s used in teabags? Nope. Let’s drop another grade.

After the processing facility has sorted out all of the Pekoe and Broken Pekoe grades, what’s left is known as “fannings.” Grades like PF (Pekoe Fannings), FOF (Flowery Orange Fannings), and TGFOF (Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Fannings). These are the grades used in most decent-quality teabags (high-end teabags may use whole-leaf teas, typically in a sachet-style bag).

“Decent-quality teabags?” I hear you cry. “Are you implying there’s another grade below fannings?”

Yes. Yes I am.

The smallest-sized particles of tea — too small to be fannings — are called “dust.” There are different grades of dust, of course, depending on the tea leaves they come from. You may encounter PD (Pekoe Dust), GD (Golden Dust), FD (Fine Dust), and others. Typically, though, grades like that don’t make it onto commercial packaging.

So these lower grades suck?

No, I didn’t say that.

Fannings from an extraordinary tea will produce a much better drink than whole leaves from a mediocre tea. There are a lot of factors to take into consideration, but the number one factor is your own preferences. As I’ve said before on this blog, I’m not a tea Nazi. It won’t hurt my feelings a bit if you prefer the cheapest grade of Lipton teabags to my shop’s whole-leaf FTGFOP-1 First Flush Darjeeling. In fact, it would be quite a waste of money to buy a tea you don’t like.

In a way, buying tea that’s highly-graded on the pekoe system is like buying organic. What it really tells you is that you’re dealing with a legitimate tea producer that cares enough about their product to pick it right and have it graded by experts.

Whole Leaf Tea

I try not to be a tea snob (or a Tea Nazi). You drink what you like and I’ll drink what I like. But being a part of the tea industry means I hear from a lot of people with — shall we say — very strong opinions. One thing we all seem to agree on is that we really prefer loose leaf tea to teabags. But why is that?

I try not to be a tea snob (or a Tea Nazi). You drink what you like and I’ll drink what I like. But being a part of the tea industry means I hear from a lot of people with — shall we say — very strong opinions. One thing we all seem to agree on is that we really prefer loose leaf tea to teabags. But why is that?

There’s a quality difference, perceived if not always actual. Ask a tea snob about Lipton tea and they’ll tell you those teabags are filled with the floor sweepings left over after all of the good stuff was packed up. There’s a hint of truth to it: the tea isn’t swept up from the floor, but it’s often fannings or dust. There’s a good reason for that, too. By breaking those tea leaves into tiny pieces, the water has much more surface area to interact with. That’s why teabags often produce a heartier, stronger, and more “brisk” cup of tea.

You can get larger leaf teas in bags, though, and the “pyramid” or “sachet” bags allow much more flow of the water through the leaves. Still, argue many in the business, the highest grades of tea are typically reserved for sale as bulk loose leaf tea, and that gives us a better-tasting cup when we use loose leaf.

There’s another factor, though. One that’s as much based on aesthetics as taste. I like the whole leaf teas because I like the leaves themselves. The picture above shows dry and wet leaves from a whole leaf Royal Golden Safari, one of my favorite black teas. It’s a whole-leaf black tea from Kenya. After you’ve steeped it, you can see the leaves and buds fully unrolled. You can smell the leaf, feel the texture. You can see the size and shape of the leaf. Experiencing the leaves becomes a part of experiencing the cup of tea.

Wine drinkers enjoys more than just the taste of the wine. They’ll swirl the wine in the glass to bring out the nose, watch the legs as it runs down from the rim, examine the cork for hints of how the wine aged. The tea equivalent is watching the “agony of the leaf” as the tea leaves expand fully in the pot or infuser, holding the leaf and comparing its smell to the aroma of the brewed tea, and examining the leaves to glean what information you can about the origin and preparation of the tea.

What is “brisk”? The Lipton people say it means “astringent.” I might say it refers to a cool afternoon on the back deck watching tea leaves unfurl in hot water as I anticipate the luscious cup that I am soon to enjoy.

A Nice Cup of Tea

On January 12, 1946, the Evening Standard published an essay by George Orwell entitled “A Nice Cup of Tea.” Like almost everyone else in my generation, I had to read his books Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm in school. They told us a lot about society and a lot about English culture, but not much about tea.

Orwell was British, and born in 1903. These two facts tell you a lot about how he viewed tea. I’ve written before about “Tea Nazis,” who believe that their way of preparing tea is the only way to prepare tea, and this essay is a marvelous example of that philosophy in action.

He opens the essay by saying that if you look up “tea” in a cookbook it’s likely to be unmentioned. That was very true in 1946. It is less true now, but even though there are a lot of wonderful books about tea, mainstream cookbooks generally find it unnecessary to describe how to prepare a pot (or a cup) of tea.

Orwell continues by pointing out that tea is a mainstay of civilization in England, yet the “best manner of making it is a subject of violent disputes.” Judging from conversations I’ve had with British friends, I’d have to agree with that. His next paragraph sets the tone for everything that follows:

“When I look through my own recipe for the perfect cup of tea, I find no fewer than eleven outstanding points. On perhaps two of them there would be pretty general agreement, but at least four others are acutely controversial. Here are my own eleven rules, every one of which I regard as golden:”

Since in my humble opinion just about everything related to preparing tea is subjective, I’d like to present my own take on Orwell’s eleven rules. Lets look at them one at a time.

“First of all, one should use Indian or Ceylonese tea. China tea has virtues which are not to be despised nowadays — it is economical, and one can drink it without milk — but there is not much stimulation in it. One does not feel wiser, braver or more optimistic after drinking it. Anyone who has used that comforting phrase ‘a nice cup of tea’ invariably means Indian tea.”

Here, I must vehemently disagree with Mr. Orwell. Perhaps the fact that he was born in India is showing through here. There is excellent tea from China (and Japan and Kenya and Taiwan…). If you want a beverage that will make you feel “wiser, braver or more optimistic,” I would recommend tequila. If you want tea that tastes good, you can find it all over the world.

Incidentally, when Orwell refers to “Ceylonese” tea, he means tea from the country that was called Ceylon when he wrote this essay, but became Sri Lanka when it achieved independence in 1948. We still typically call tea from Sri Lanka “Ceylon” tea.

“Secondly, tea should be made in small quantities — that is, in a teapot. Tea out of an urn is always tasteless, while army tea, made in a cauldron, tastes of grease and whitewash. The teapot should be made of china or earthenware. Silver or Britannia-ware teapots produce inferior tea and enamel pots are worse; though curiously enough a pewter teapot (a rarity nowadays) is not so bad.”

He has an excellent point about the small quantities. To me, this means preparing it by the cup rather than by the pot, and there is a lot of excellent teaware available for that purpose. Although china, earthenware, and ceramic teapots do add something to the tea, using plastic or glass pots allows you to watch the tea steep. It also adds (and detracts) nothing to the flavor.

“Thirdly, the pot should be warmed beforehand. This is better done by placing it on the hob than by the usual method of swilling it out with hot water.”

I agree that pre-warming the pot helps to keep the water hot as the tea steeps.

“Fourthly, the tea should be strong. For a pot holding a quart, if you are going to fill it nearly to the brim, six heaped teaspoons would be about right. In a time of rationing, this is not an idea that can be realised on every day of the week, but I maintain that one strong cup of tea is better than twenty weak ones. All true tea-lovers not only like their tea strong, but like it a little stronger with each year that passes — a fact which is recognized in the extra ration issued to old-age pensioners.”

My biggest problem with this “rule” is the statement that “all true tea-lovers not only like their tea strong.” In fact, many tea lovers like a shorter steeping time so that the flavor of the tea isn’t overwhelmed by the bitterness and tannins that come out later in the steep.

“Fifthly, the tea should be put straight into the pot. No strainers, muslin bags or other devices to imprison the tea. In some countries teapots are fitted with little dangling baskets under the spout to catch the stray leaves, which are supposed to be harmful. Actually one can swallow tea-leaves in considerable quantities without ill effect, and if the tea is not loose in the pot it never infuses properly.”

Philosophically, he’s right. Allowing the water to circulate freely through the leaves does improve the infusion process. I do prefer not to consume the leaves (unless I’m drinking matcha), but a proper modern infuser will catch pretty much all of them.

“Sixthly, one should take the teapot to the kettle and not the other way about. The water should be actually boiling at the moment of impact, which means that one should keep it on the flame while one pours. Some people add that one should only use water that has been freshly brought to the boil, but I have never noticed that it makes any difference.”

Clearly, Mr. Orwell was aware of only one kind of tea: black. While boiling water is the right way to go for black and pu-erh tea, you get much better results with green and white tea if you use cooler water. I won’t get into the oolong debate at the moment…

The little aside that he snuck in here about freshly-boiled water is perhaps the biggest point of argument I hear from tea lovers. Does your tea really taste different if the water is heated in a microwave instead of being boiled in a teapot? Does the tea taste different if you reboil water that has been boiled before? In a blind taste test, I can’t tell the difference. Perhaps you can.

“Seventhly, after making the tea, one should stir it, or better, give the pot a good shake, afterwards allowing the leaves to settle.”

I confess. I do this.

“Eighthly, one should drink out of a good breakfast cup — that is, the cylindrical type of cup, not the flat, shallow type. The breakfast cup holds more, and with the other kind one’s tea is always half cold — before one has well started on it.”

Your cup is as personal as your clothing or your car. Most of the time, I use a 16-ounce ceramic mug made by a local potter. When I’m trying a new tea, I make the first cup in a glass mug so I can see it better. I typically use a smaller cup for matcha, a bigger one for chai lattes, and a bigger one than that for iced tea.

“Ninthly, one should pour the cream off the milk before using it for tea. Milk that is too creamy always gives tea a sickly taste.”

Unless I’m drinking chai, I do not add milk to my tea. I have made the occasional exception (I actually like milk in purple tea), but I generally prefer to taste the tea, not the milk.

“Tenthly, one should pour tea into the cup first. This is one of the most controversial points of all; indeed in every family in Britain there are probably two schools of thought on the subject.

The milk-first school can bring forward some fairly strong arguments, but I maintain that my own argument is unanswerable. This is that, by putting the tea in first and stirring as one pours, one can exactly regulate the amount of milk whereas one is liable to put in too much milk if one does it the other way round.”

When I make chai, I don’t use either of Orwell’s methods. I find that the spices extract better with the lipids in the milk present than they do in water alone. In other words, I heat the milk and add it to the water while the tea is steeping. It changes the flavor considerably.

When I’m adding milk to any other tea, I typically put it in the cup first and then add tea to it.

“Lastly, tea — unless one is drinking it in the Russian style — should be drunk without sugar. I know very well that I am in a minority here. But still, how can you call yourself a true tea-lover if you destroy the flavour of your tea by putting sugar in it? It would be equally reasonable to put in pepper or salt.”

Good point, Mr. Orwell. Now please substitute the word “milk” for “sugar” in this paragraph. Then go back and read rule nine. I don’t sweeten my tea (chai being the exception again — I like some honey in it), but I see nothing wrong with doing so. Adding a bit of sugar is no different than adding a bit of milk.

Oh, and by the way, tea was traditionally prepared in salt water in ancient China. And one of my favorite chai blends does, indeed, contain pepper.

Orwell continues…

“Tea is meant to be bitter, just as beer is meant to be bitter. If you sweeten it, you are no longer tasting the tea, you are merely tasting the sugar; you could make a very similar drink by dissolving sugar in plain hot water.

Some people would answer that they don’t like tea in itself, that they only drink it in order to be warmed and stimulated, and they need sugar to take the taste away. To those misguided people I would say: Try drinking tea without sugar for, say, a fortnight and it is very unlikely that you will ever want to ruin your tea by sweetening it again.”

Again, Orwell is speaking only of black tea here. I do not expect bitterness in, for example, a Long Jing Dragonwell green tea. And I would argue that there are a lot of fine black teas that have minimal bitterness: Royal Golden Safari from Kenya, to pick a favorite of mine.

If I had to pick one issue to argue in this essay, it would be that George Orwell considers all tea to be the same (after eliminating the majority of the world’s production by limiting himself to India and Sri Lanka). Even within the world of black tea, there is immense diversity. I don’t use the same preparation methods or expect the same results for a malty Assam tea and a delicate first flush Darjeeling — much less a smoky Chinese lapsang souchong.

My recommendation? Experiment. Try new teas, and try them first without adding milk or sweetener. Use your supplier’s recommended water temperature and steeping time. Taste the tea. THEN decide whether you want to steep it for a shorter or longer time; whether it needs a bit of milk; whether you’d prefer to sweeten it.

The best tea is your favorite tea, prepared just the way you like it.

Tasting purple tea

Today, I received my first shipment of the purple tea that I blogged about back in August. I opened the bag with no preconceptions, as I haven’t read anyone else’s tasting notes.

The leaves look like pretty much any black tea. Not surprising, as the purple tea plant (TRFK306/1) can be prepared using any tea process, and this was oxidized like a traditional (orthodox) black tea. This is a very dense tea. The kilogram bag I purchased was the same size as the half-kilo (500g) bag of Golden Safari (a Kenya black I’ll be writing about soon).

I took a deep whiff, and picked up a slight earthiness to it that isn’t present in the other Kenya black teas I’ve tried. Not as extreme as a shu pu-erh, of course, as there was no fermentation in the process, but enough to distinguish the aroma from a traditional black tea.

Actually, despite my previous comment, I did come in to this with one preconception. Since this is a high-tannin tea, I expected a fair amount of astringency (“briskness,” as Lipton calls it), so I decided to take it easy on the first cup and make it like I make my 2nd-flush Darjeelings: 5 grams of leaves, 16 ounces of water at full boil, and a scant two-minute steep time.

“I did not expect purple, as the anthocyanin that gives purple tea its name doesn’t affect the color of black tea.”

The leaves settled immediately to the bottom of the pot, and I was taken by surprise by the color. I did not expect purple, as the anthocyanin that gives purple tea its name doesn’t affect the color of black tea. But I also didn’t expect the pale greenish tan color that immediately appeared (it later mellowed to a deep black with — you guessed it, a purplish tinge). We don’t have any analyses yet of total antioxidant content, but we know that the anthocyanin does contribute quite a bit.

My first taste of the purple tea was impressive. Rich, complex, and a bit more astringent than you’d expect with only a two-minute brewing time. The earthiness in the aroma comes through subtly in the taste, and there’s a silky mouthfeel that lingers on the back of the tongue.

I figured that there was enough going on in that tea that it could hold up to a second infusion, so I brewed a second cup off of the same leaves. This time I gave it a three-minute steep, and it came out tasting very similar to the first brew, although a bit more pale in color.

“Purple tea is certainly not cheap.”

All in all, I’m pleased and excited to have this new varietal available at the tea bar. Purple tea is certainly not cheap. At $16.00 per ounce, it’s one of the priciest teas on our menu, but I expect it to build a fan base quickly. Our new tea website isn’t quite ready to launch yet (I’ll make a big announcement here when it is), but if you’d like to order some Royal Purple tea, just call the store (406-446-2742) or send an email to gary (at) redlodgebooks (dot) com. We’re ready to ship right away.

UPDATE MAY 2012: Our tea website is up and running, and Royal Purple tea is now available for purchase.

More more information about purple tea, please see my earlier blog post announcing and describing the varietal.

Kenya will be growing Purple Tea

According to Business Daily in Africa, farmers in Kenya have been given permission to start growing purple tea, a varietal they’ve been developing for the last 25 years. The new varietal, called TRFK306/1, was developed by the Tea Research Foundation of Kenya (TRFK), and is expected to provide dramatically higher profits for farmers than existing tea plants.

Unlike white, green, and black tea — which all refer to different ways of processing tea leaves — purple tea is actually a variant of the plant. It can be processed in different ways to yield “black purple tea” or “green purple tea,” as confusing as that terminology might be (kind of like the “green red rooibos” I wrote about recently.

All “true” tea is produced from the same plant: Camellia sinensis. There are two main variants of the plant, known as var. sinensis (Chinese) and var. assamica (Assam), and hundreds of sub-varieties. The new purple tea cultivar is what’s known as a “clonal” cultivar, meaning it is propagated by cutting and grafting rather than seed.

It is called “purple” because of high amounts of anthocyanin. The anthocyanin gives the leaves a purplish color in the fall, and contributes more astringency (what Lipton calls “briskness”) to the taste than standard varieties. People who drink tea for its healthy properties will be more interested, however, in the powerful antioxidant properties of anthocyanin.

According to New Agriculturalist, the strain is also higher yielding than existing Kenya teas, and is drought-resistant and frost-resistant. (Hmmm. Drought and frost resistant tea plants. I wonder how they would do here in Montana?) The TRFK told Reuters that the seeds “produce oil suitable for cooking, cosmetics and the pharmaceutical industries.” Kenya is the world’s third-largest producer of tea, after China and India, but it is the largest exporter of tea, according to FAO statistics.

How will this affect us in the U.S.?

Fans of black teas typically prize astringency (the “puckeriness” provided by the tannins in the tea, also found in wines like merlot), which purple tea processed like oolong will provide more of. People looking for a healthier beverage often seek out the teas with the highest antioxidant content, which lead them to white and green teas. Green purple tea should provide more of the antioxidants (although the jury is still out on the affect of anthocyanin on free radicals) while filling a new taste niche. I’ve only found one review of the flavor (apparently it’s “earthy and rustic”), so I’m holding off on expressing an opinion there until I get some myself.

It will probably be next year or the following before any significant quantity of purple tea shows up in the United States. I’m not going to jump on the health bandwagon, but I’ll certainly be one of the first to give it a taste and bring some in for the tea bar when the price becomes a bit more reasonable.