Blog Archives

Millennials & Tea

When a new study comes out, it’s interesting to see who spins it how. YouGov released a survey last month comparing American consumption of tea with coffee. Their headline was “Coffee’s millennial problem: tea increasingly popular among young Americans.” Oh, no! A coffee problem!

World Tea News, on the other hand, reported that same survey with the headline, “America’s Youth Embrace Tea.” Oh, boy! Kids are drinking tea.

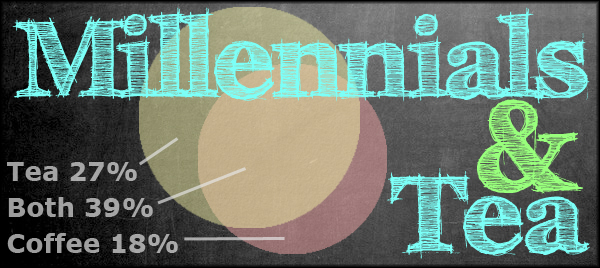

Most of the articles I read about the survey included this handy-dandy chart:

It pretty clearly indicates that the younger you are, the more likely you are to prefer tea to coffee. The statistic I liked, on the other hand, I turned into the Venn diagram on my header for this article. Of Americans aged 18-29, 18% drink coffee, 27% drink tea, and 39% drink both (the remaining 17% don’t drink either one). In case you’re interested, 998 people were surveyed and 143 of them were in that “millennial” age range of 18-29.

I’m sure there are some people in the tea business that are saying, “This is marvelous! We just have to sit back and wait and we’re going to own this market!” Others are saying, “We really need to get people over 30 to drink more tea.” The coffee industry, of course, has known about this trend for years. That’s why Starbucks bought Tazo and Teavana.

Being a numbers geek, I decided to pull up the PDF of the full report and do a bit of digging. Here are some interesting points you might enjoy:

- The under-30 crowd is much more likely than the older crowd to drink neither coffee nor tea.

- Blacks are over twice as likely to drink tea only (no coffee) than whites or hispanics.

- 64% of Republicans prefer coffee, vs 55% of Democrats and 52% of independents.

- 33% of independents prefer tea, vs 32% of Democrats and 28% of Republicans.

- Middle-income Americans earning $40K-$80K/year are more likely to prefer tea than higher or lower-income Americans.

- 42% of people surveyed are trying to limit their coffee intake vs only 25% that are trying to limit tea.

- Women are much more likely to prefer tea than men

So let’s see here. A tea shop’s target audience is young women? This comes as a surprise to absolutely nobody in the tea business.

I confess that I didn’t expect some of these results. Since Montana is 89% white and 0.4% black, I don’t really have a statistically significant sampling to judge African-American preferences. I do see, however, quite a few Native Americans in the shop getting tea, although I haven’t tried doing any statistical analysis there.

To what do I attribute the tea-drinking millennial trend? The obvious factor is healthier lifestyles, but I would posit something else as well: younger folks are better informed about tea.

I am much more likely to hear an older person say, “I don’t like tea,” because back in their day, tea meant either a teabag full of basic Lipton black tea or the green tea at a Chinese restaurant. Millennials are more likely to have discovered tea in a tea shop that offers dozens — or hundreds — of options. That person who doesn’t like tea may never have tried masala chai, or oolong, or pu-erh, or white tea, or the huge variety of flavored, spiced, and scented options. They’ve probably never experienced the difference between that teabag full of dust and an FTGFOP-1 golden black whole-leaf tea. They may still be under the mistaken impression that latte means coffee, leaving them blissfully unaware of the wealth of tea lattes awaiting them in a good tea shop.

I’ve said many, many times that if you work in the tea business today, your primary job is education. I think this survey shows that tea education is working. Sure, we still sell your basic Earl Grey tea, but younger folks like the ladies in the picture above are well educated about their options. You’re as likely to see them sipping whole-leaf black Vietnamese tea or Indian oolong as you are a peach-flavored white tea or a sage Earl Grey (popular in our corner of Montana).

So let’s get out there and buy Grandma a great cup of tea!

While writing this post, I was drinking Jasmine King Silver Needle tea. It’s a delicate white tea perfectly scented with jasmine blossoms, so that you get the aroma of the jasmine and the flavor of the tea. Yes, jasmine isn’t just for green tea anymore. Hey, that’s a great tagline. Look for it as a blog post title one of these days!

Tea and caffeine part I: What is caffeine?

The most popular drug?

This article is the first of a three-part series.

Part I: What is caffeine?

Part II: Exploding the myths

Part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

In his excellent book, A History of the World in 6 Glasses, Tom Standage selected the six beverages that he felt had the greatest influence on the development of human civilization. Three of the six contain alcohol; three contain caffeine. Tea was one of the six.

Is it the caffeine that has made tea one of the most popular beverages in the world? The flavor? Its relaxing effects? I think that without caffeine, Camellia sinensis would be just another of the hundreds of plant species that taste good when you make an infusion or tisane out of it. Perhaps yerba maté would be the drink that challenged coffee for supremacy in the non-alcoholic beverage world.

“Caffeine is the world’s most popular drug”

The above quote opens a paper entitled Caffeine Content of Brewed Teas (PDF version here) by Jenna Chin and four others from the University of Florida College of Medicine. I’ll be citing that paper again in Part II of this series. Richard Lovett, in a 2005 New Scientist article, said that 90% of adults in North America consume caffeine on a daily basis.

But yes, caffeine is a drug. It is known as a stimulant, but its effects are more varied (and sometimes more subtle) than that. It can reduce fatigue, increase focus, speed up though processes, and increase coordination. It can also interact with other xanthines to produce different effects in different drinks, which is one reason coffee, tea, and chocolate all affect us differently.

Tea, for example, contains a compound called L-theanine, which can smooth out the “spike & crash” effect of caffeine in coffee and increase the caffeine’s effect on alertness. In other words, with L-theanine present, less caffeine can have a greater effect. See a great article from RateTea about L-theanine here.

Even though Part II of this series is the one that dispels myths, I really need to address a common misconception right now. First, I’m going to make sure to define my terms: for purposes of this series, “tea” refers to beverages made from the Camellia sinensis plant (the tea bush) only. I’ll refer to all other infused-leaf products as “tisanes.” Okay, now that we have that out of the way:

“All tea contains caffeine”

Yes, I said ALL tea. The study I mentioned a couple of paragraphs ago measured and compared the caffeine content of fifteen regular black, white, and green teas with three “decaffeinated” teas and two herbal teas (tisanes). With a five-minute steep time, the regular teas ranged from 25 to 61 mg of caffeine per six-ounce cups. The decaf teas ranged from 1.8 to 10 mg per six ounce cup.

That’s right. The lowest caffeine “regular” tea they tested (Twinings English Breakfast) had only 2-1/2 times the caffeine of the most potent “decaffeinated” tea (Stash Premium Green Decaf).

There are two popular ways to remove caffeine from tea. In one, the so-called “direct method,” the leaves are steamed and then rinsed in a solvent (either dichloromethane or ethyl acetate). Then they drain off the solvent and re-steam the leaves to make sure to rinse away any leftover solvent. The other process, known as the CO2 method, involves rinsing the leaves with liquid carbon dioxide at very high pressure. Both of these methods leave behind some residual caffeine.

(As a side note: I’m not a fan of either process. When I don’t want caffeine, I’d much rather drink rooibos than a decaf tea. I only have one decaf tea out of over 80 teas and 20 tisanes at my tea bar, and I’m discontinuing that one.)

This is why tea professionals need to make a strong distinction between the terms “decaffeinated” (tea that has had most of its caffeine removed) and “naturally caffeine-free” (tisanes that naturally contain no caffeine such as rooibos, honeybush, and chamomile).

“Coffee has more caffeine than tea”

Almost everyone will agree with the statement. For the most part, it is true, assuming you add some qualifiers: The average cup of fresh-brewed loose-leaf tea contains less than half the caffeine of the average cup of fresh-brewed coffee. In the seminar, Tea, Nutrition, and Health: Myths and Truths for the Layman, at World Tea Expo 2012, the studies Kyle Stewart and Neva Cochran quoted showed the plain cup of fresh-brewed coffee at 17 mg of caffeine per ounce versus the plain cup of fresh-brewed tea at 7 mg per ounce (that’s 42 mg per six-ounce cup, which agrees nicely with the numbers from the caffeine content study I quoted above).

Interestingly, though, a pound of tea leaves contains more caffeine than a pound of coffee beans. How can that be? Because you use more coffee (by weight) than tea to make a single cup, and caffeine is extracted more efficiently from ground-up beans than from chunks of tea leaf. Tea is usually not brewed as strong as coffee, either.

At another 2012 World Tea Expo seminar, A Step Toward Caffeine and Antioxidant Clarity, Kevin Gascoyne presented research he had done comparing caffeine levels in dozens of different teas (plus a tisane or two). The difference between Kevin’s work and every other study I’ve seen is that he prepared each tea as people would actually drink it. For example, the Bai Mu Dan white tea was steeped 6 minutes in 176-degree water, while the Tie Guan Yin (Iron Goddess of Mercy) oolong was steeped 1.5 minutes in 203-degree water. Matcha powder was not steeped per se, but stirred into the water and tested without filtering.

The results? Caffeine content ranged from 12mg to 58mg for the leaf teas, and 126mg for the matcha — which is higher than some coffees.

In our next installment, I’ll look at the myths regarding caffeine in tea, including what kinds of tea have the most caffeine and how you can remove the caffeine at home all by yourself — or can you?

Complicated drinks, education, and consistency

Jul 7

Posted by Gary D. Robson

Is there some particular tea concoction that’s “your” tea drink? Is it something complicated? You’ll hear people every day in Starbucks ordering coffees that take twenty words to describe, but we don’t run in to that much in the tea bar … yet.

Why is it that more coffee drinkers than tea drinkers tend to be like the guys in this PVP Online comic? I think it’s a matter of education and consistency.

Most of our regulars at the tea bar are like me: they order something different each time they come in. I may go through phases where I drink nothing but malty Assam for a few days, but then I’m back to switching it up. I also drink different tea in the morning than I do in the afternoon or evening. Of course, I’m also that annoying guy that will go into a bar four times, order something completely different each time, and then ask for my “regular” on the fifth visit.

We do have some regulars that are consistent, but their drinks tend to be simple: a cup of sencha, Scottish breakfast with a touch of milk, or iced mango oolong. As people learn the menu and zero in on what they like, that is beginning to change a bit, though.

Amber is from the South. She likes her tea sweet, and she loves boba tea (a.k.a. “bubble tea”). I finally put the “Amber special” on the menu so she didn’t have to describe her boba tea made with Cinnamon Orange Spice tea, vanilla soy milk, and triple the usual sweet syrup.

Phyllis isn’t much of a tea fan, but she found herself drawn to Hammer & Cremesickle Red, which is a rooibos/honeybush blend. She likes it prepared as a latte with frothed 2% milk and a bit of honey.

Starbucks has dramatically changed coffee culture, much as McDonald’s has changed restaurants (I’m going to catch grief for that one, I know, but keep reading). You can go into a McDonald’s in an unfamiliar city, and you know that Big Mac and fries will be just like the ones back home. Similarly, you can go into any one of 19,555 Starbucks franchises and be comfortable that your half-caf double-shot venti skinny hazelnut macchiato will taste just like it would from the franchise back home. They have taught the world their own terminology (education) and made sure that the drinks are prepared exactly the same at each franchise (consistency).

Let’s look at those two factors as they apply to tea:

Consistency

The world of tea is generally not a good place for consistency. Even for fans of a single type of tea, the options are legion. There are dozens of matchas, hundreds of oolongs, and each has its own unique flavor. My tea bar offers six types of milk (nonfat, 2%, whole, half-and-half, vanilla soy, and almond), where another may offer 1%, light soy, and whole. When I went into the tea business’ closest thing to a national chain (Teavana – you can read about my visit here), they didn’t offer milk at all. You may go into one tea shop that has a hundred Chinese green and white teas and an English tea shop that has only black teas.

There’s a strong parallel to be drawn here with independent bookstores and big chains. You can find exactly the same books at a Barnes & Noble in Austin, Texas as you’d find in San Francisco, Denver, or New York. On the other hand, two indie bookstores a block apart can offer completely different experiences.

Tea aficionados revel in this. I enjoy wandering into a tea shop that has dozens of different pu-erhs available and tasting something I’ve never had before, even though I know the odds of finding that 1935 Double Lions Tongqing Hao anywhere else are close to zero (and the odds of being able to afford it are similar).

Tea shops can help a lot with this problem by proper labeling and by knowing the products well enough to compare our wares with popular brands from elsewhere. If someone walks into my shop that likes Constant Comment, I can guide them to my closest loose-leaf blend (that would be the aforementioned Cinnamon Orange Spice). If someone buys a mountain-grown Wuyi oolong in my shop, the next tea shop they visit should be able to give them something with a similar flavor profile.

Consumers can help by asking questions. If I have a breakfast tea I enjoy, I’ll ask the shopkeeper what’s in the blend. Then I’ll know to ask for an Assam/Tanzanian black breakfast tea blend next time I want something similar. I watch (or ask) how much leaf they use and what temperature the water is. Again, if I don’t know how they brewed it, I can’t ask for it to be prepared that way next time.

Education

The tea industry is where coffee and wine were a few decades ago. The average person has no idea what the difference is between a green tea and a white tea, but they know the difference between Merlot and Chardonnay. Tea people need to focus on education the same way wine and coffee people have done.

Educating customers is a bad thing for the mediocre shops. The more people learn about tea, the less likely they are to buy lower-grade products, and the less likely they are to buy from people who don’t know what they’re talking about. Once the person who’s been buying pre-sweetened chai from a box tastes fresh-brewed chai, they won’t be switching back.

On the other hand, education is a great thing for consumers and for good tea shops.

The more you know as a consumer, the better you’re able to find what you like and recognize the good products (and good prices). Educated consumers will frequent the better shops, and spend more money there, benefiting both the shop and the customer.

Share this:

Posted in Brewing

2 Comments

Tags: boba tea, chai, coffee, consistency, Constant Comment, education, McDonald's, PVP Online, Scott Kurtz, Starbucks, tea, wine