Category Archives: Tisanes

Yerba mate

Let’s get this out of the way first: is it spelled yerba mate or maté? Normally, when words from other languages are adopted into English, their accent marks go away. In this case, it’s the other way around. In both Spanish and Portuguese, the word is spelled mate and pronounced MAH-tay. No accent mark is used, because it would shift the emphasis to the 2nd syllable. The word maté in Spanish means “killed.”

In the United States, people unfamiliar with the drink see “yerba mate” written on a jar in a tea shop and pronounce mate to rhyme with late. So it has become accepted in English to add the accent above the e just to help us pronounce the word right. Linguists call this a hypercorrection.

Yerba, on the other hand, is spelled consistently in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, but the pronunciation varies depending on where you are. As you move across South America, it shifts from YER-ba to JHER-ba.

Directly translated, a mate is a gourd, and yerba is an herb, so yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) is literally the herb you drink from a gourd. I don’t really care which way you spell (or pronounce) the word as long as you give this delicious drink a try!

Yerba mate is a species of holly that contains caffeine (not, as previously thought, some related molecule called mateine). It grows in Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, and is the caffeinated beverage of choice for many people who live in those countries.

In the U.S., mate is usually made like tea, with the leaves steeped in boiling water for a few minutes and then removed. This, however, isn’t the way Argentinian gauchos (cowboys) been drinking mate in South America for centuries.

The process uses four elements: dried yerba mate leaves, hot water, a gourd (mate), and a bombilla (straw). Bombilla is another word that varies in pronunciation in different parts of South America, ranging from BOM-bee-ya to BOM-beezh-a.

Drinking mate was a social time for the gauchos and still is throughout much of South America. You generally won’t find yerba mate served this way in a U.S. tea shop, because it’s darned near impossible to clean a natural gourd to health department standards.

- First, the host (known as the cebador), fills the gourd about 1/2 to 2/3 full of leaf. Yeah, that’s a lot of leaf, but we’ll get a lot of cups out of it!

- Next, the cebador shakes or taps the gourd at an angle to get the fine particles to settle to the bottom and the stems and large pieces to rise to the top, making a natural filter bed. Before pressing the bombilla against the leaves, dampening them with cool water helps to keep the filter bed in place.

- Finally, the cebador adds the warm water. The water is warm (around 60-70°C or 140-160°F) rather than boiling, because boiling water may cause the gourd to crack—and your lips simply won’t forgive you for drinking boiling water through a metal straw!

In most of the world’s ceremonies, the host goes last, always serving the guests first. The mate ceremony doesn’t work that way. That first gourd full of yerba mate is most likely to get little leaf particles in the bombilla, and can be bitter. So the cebador takes one for the team and drinks the first gourdful.

After polishing off the first round, the cebador adds more warm water and passes the gourd to the guest to his or her left. The guest empties the gourd completely (you share the gourd, not the drink!), being careful not to jiggle around the bombilla and upset the filter bed, and passes the gourd back to the cebador.

The process repeats, moving clockwise around the participants, with everyone getting a full gourd of yerba mate. A gourd full of leaves should last for at least 15 servings before it loses its flavor and becomes flat.

Teas, Tisanes, and Terminology

Language evolves. I get that. Sometimes changes make communication easier, clearer, or shorter. Sometimes, however, the evolution of the meaning of a word does exactly the opposite. The subject of this blog is a good example.

The word “tea” refers to the tea plant (Camellia sinensis), the dried leaves of that plant, or the drink that is made by infusing those leaves in water.

The word “tisane” refers to any drink made by infusing leaves in water. Synonyms include “herbal tea” and “herbal infusion.”

Technically speaking, all teas are tisanes, but most tisanes are not teas.

In today’s culture, however, practically anything (except coffee and cocoa) that’s made by putting plant matter in water is called a tea. What’s my problem with that? It makes communication more difficult, less clear, and less terse.

- There is no other single word that means “a drink made with Camellia sinensis.” If we call everything tea, then we have to say “real tea” or “tea from the tea plant” or “Camellia sinensis tea” or something similarly ludicrous every time we want to refer specifically to tea rather than to all tisanes.

- There is a perfectly good word for “leaves infused in water.” There is no need to throw away “tisane” (or “herbal tea” or “infusion”) and replace it with a word that already has another meaning.

“But Gary,” I hear you cry, “people have been calling herbal infusions ‘tea’ for a long time!”

That’s true. I sometimes slip and call rooibos a tea myself. “Herbal infusion” is even an alternate definition of tea in the OED. I still maintain, however, that it makes clear, precise communication more difficult when trying to differentiate between tea (made from the Camellia sinensis plant) and drinks made from chamomile, honeybush, and willow bark.

Rooibos

Other words that go through this process are forced through it. Rooibos, for example, is the name for a specific tisane and the plant it’s made from (Aspalathus linearis). The word is Afrikaans for Red Bush. Despite the longtime use of the term in South Africa (the only place the rooibos plant grows), it was almost unknown in the United States in 1994 when Burke International of Texas registered “rooibos” as a trademark. This meant that in the United States, only Burke and its subsidiaries could use the common name of the plant. Had Burke not surrendered the trademark after starting to lose lawsuits, people would have been forced to come up with a new word.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t a decisive victory, as the South African Rooibos Council is being forced to repeat the process now with a French company.

As more people in the U.S. discover green rooibos, the name “red bush” becomes more confusing anyway. Rooibos, in my humble opinion, should remain the generic term here.

Oxidation vs. fermentation

There are other words in the tea industry that suffer from ambiguity and questionable correctness. You will find quite a bit of tea literature that refers to the oxidation of tea as fermentation. I had a bit of a row with Chris Kilham — The “Medicine Hunter” on Fox News — about this subject (it starts with “Coffee vs. Tea: Do your homework, Fox News” and continues with “Chris Kilham Responds“).

Fermentation and oxidation are closely related processes. That’s certainly true. But oxidation is the aerobic process that is used in the production of black and oolong tea, and fermentation is the anaerobic process that’s used in the production of pu-erh tea. Using the word “fermentation” to describe the processing of black tea may fit with a lot of (non-chemist) tea industry writers, but it makes it difficult to explain what real fermented tea is.

Precision matters

In chatting with friends, imprecise use of words doesn’t matter. If someone asks what kind of tea you want and you respond, “chamomile,” it’s perfectly clear what you want. But you’re an industry reporter, medical writer, or marketing copywriter, your job is to communicate unambiguously to your readers. Using the most correct terminology in the right way is a great way to do that.

Rooibos: The African Red Bush

How have I been at this blog for so long without writing about rooibos? Oh, I know this blog is about tea, and I did write a post about green rooibos last year, but I haven’t covered straight red rooibos yet.

Rooibos comes from a bush called Aspalathus linearis, which grows in the west cape of South Africa. The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans.

Rooibos is also often called “red tea,” but most tea professionals shy away from that name for several reasons:

- The term “red tea” is used by the Chinese to refer to what we call “black tea.” No sense having two different drinks with the same name.

- Rooibos isn’t tea, since it doesn’t come from the Camellia sinensis plant. Instead, it is a tisane or herbal infusion.

- Rooibos only has that rich red color when it’s processed like a black tea. Green rooibos is more of a golden honey-colored infusion.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Unlike “real” tea, which all has caffeine, rooibos is naturally caffeine-free. Since the flavor is similar to a mild black tea, this makes it a favorite bedtime beverage for many tea drinkers. Rooibos is also high in antioxidants.

Herbalists make many claims about the health properties of the rooibos tisanes. The Web site for the South African Rooibos Council (SARC), in fact, has very little information that isn’t in some way tied back to health claims. There are more and more studies being done, but available data are lacking in specifics (in my opinion, anyway) so I’m not going to quote any of those there. Feel free to check SARC’s site for lots of studies.

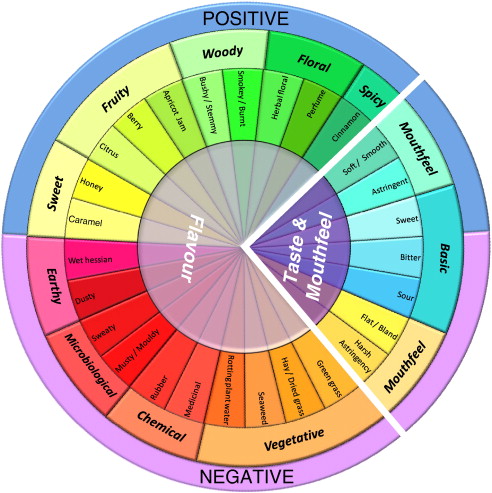

I don’t mean to imply that rooibos is only about the health benefits. It is, in fact, a very tasty drink. Most rooibos drinkers in the U.S. enjoy it straight or with a bit of sweetener (honey or sugar). In South Africa, it is commonly served with a bit of milk or lemon as well as honey. A group funded by SARC and Stellenbosch University has recently developed a “sensory wheel” for rooibos, describing both the desirable and undesirable aspects of flavor and mouthfeel. If you are interested in more information, click on the wheel below.

Rooibos Sensory Wheel as described in the article “Sensory characterization of rooibos tea and the development of a rooibos sensory wheel and lexicon,” available on Science Direct. Click the wheel above to view the article — there is a charge for the full text version.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Compared to tea, rooibos is a pretty small market. South Africa’s annual rooibos production is about 12,000 tons. That output is about equivalent to annual tea production of the Darjeeling region of India, or about a tenth of the tea production of Japan (the 8th largest tea producing country). Nonetheless, rooibos is important to South Africa, employing about 5,000 people and generating about $70 million in revenues.

The leaves of the rooibos bush are more like needles than the broad leaves of a tea plant. To produce red rooibos, the leaves are harvested, crushed, and oxidized using a process based on the one used in making Chinese black tea. Typically, the leaves are sprayed with water and allowed to oxidize for about 12 hours before being spread out in the sun to dry.

Green rooibos, as the name implies, is unoxidized or very lightly oxidized, and is processed more like a green tea.

For more information about the rooibos industry, I recommend the article Disputing a Name, Developing a Geographical Indication, from the World Intellectual Property Organization.

I’ll have a green red tea, please

I’ve been drinking rooibos (a.k.a. “African redbush,” a.k.a. “red tea”) for years, and stocked our tea bar liberally with varieties of it. All of them use the same base plant — Aspalathus linearis — prepared with an oxidation process similar to what’s used for black tea. The plant is naturally caffeine-free, which is a great boon for those of us who aren’t fans of chemical or pressure decaffeination techniques.

In green rooibos, the leaves (shaped like needles) are heated after picking to stop the oxidation process and keep the green color and mild flavor.

Rooibos has developed quite a following, especially with all of the press it’s been getting for being high in antioxidants. Only recently, however, have requests started coming in at the tea bar for “green” rooibos.

I am in the tea business because I love the flavors of tea. I’m not an herbalist, so everything I do with tea starts with the taste. I ordered in some green rooibos for the tea bar, and gave it a try. Green rooibos has minimal tannin content, so bitterness isn’t a danger. For my first try, I made a cup using 195-degree water (I’m at 5,500 feet altitude, so that’s about 7 degrees below boiling), and steeped it for 5 minutes. I used one tablespoon for a 13-ounce cup, and did not add anything (no lemon, sugar, milk…).

The first thing I noticed was the color. The liquid is a beautiful golden honey color, quite different both from most green teas and from the traditional red rooibos. The tea is smooth and woody, with just a hint of grassiness and nut flavor. True to promise, there’s no bitterness at all, and no need for additives. Just to push the limits, I re-used the leaves, steeping them for 10 minutes this time. The flavor and aroma were almost identical to the first cup.

There are a lot of claims out there about green rooibos being significantly higher in antioxidants than traditional red rooibos. A quick perusal of the research still shows mixed results on that, so I’m not going to take a position on the health effects. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m in it for the taste!

While writing this, I realized that I had tried it hot, but not iced. The folks over at Suffuse Rooibos say green rooibos makes a fantastic iced tea, so I took a break to make a cup of iced green rooibos (the research is the best part of this job!). I brewed it the same way (5-minute steep time), and poured it directly over a cup of ice cubes — again, I didn’t add anything to it. I found it refreshing and tasty; excellent for a hot day when I don’t want to overload with caffeine. I will definitely be drinking more of this!