Blog Archives

Book Review: 20,000 Secrets of Tea

I read a lot about tea (what a surprise, eh?), and try to carry a decent selection of tea books in my bookstore. When somebody recommended the book 20,000 Secrets of Tea: The Most Effective Ways to Benefit from Nature’s Healing Herbs by Victoria Zak, I decided to give it a look. I confess I was put off by the subtitle, because it sounds more like a book of herbal medicine than a book about tea. Then I flipped the book over and took a look at the back cover. There I saw this:

“An Ancient Chinese Legend: Once there was a man who knew 100,000 healing properties of herbs. He taught his son 80,000 secrets. On his deathbed, he told his son to visit his grave in five years, and there he would find the other 20,000 secrets. When the son went to his father’s grave, he found, growing on the site, the tea shrub…”

Okay, that’s more promising. Especially this line in the next paragraph: “A simple cup of tea not only has the power to soothe and relax but to deliver healing herbal agents to the bloodstream more quickly than capsules, tinctures, or infusions.” That line indicates that they know the difference between tea and infusions/tisanes, and that this book is going to be about tea.

Oh, my, was I wrong.

Page one starts out with a description of the legend of the origin of tea. Chapter one continues on, repeating the story from the back cover and then providing some of the history of tea as a drink. Within five pages, it has transitioned to herbal infusions, and that’s pretty much the end of discussion of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis).

I flipped through the next 220 pages looking for more information about tea (after all, the next 20,000 secrets are all about the tea shrub, right?) and I all found was descriptions of various herbs along with multitudinous health claims about each (more on that in a moment).

I went to the index looking for tea. The index is 15 pages long, normally a good sign in a reference book. Under “tea” I found reference to pages 1-4, mentioned above. Under Camellia sinensis, nothing. Flipping through the alphabetical collection of herbs, tea isn’t even listed. I checked under “black tea” and found a two-page spread in the middle titled “Green, Oolong, Black: the legendary teas.”

Zak begins by repeating the origin legend from page 1, and then proceeds to talk about fermentation (none of those teas are fermented, although black and oolong are oxidized) and rates the three styles in order of “medicinal strength: (green, then oolong, then black). Nowhere does she mention white or pu-erh tea, and nowhere does she define what “medicinal strength” actually means. Obviously, when there’s so little information, it leads to gross overgeneralization. When you use up that little bit of space with statements like “Green tea’s polyphenols are powerful antioxidants are reputed to be two hundred times stronger than vitamin E. It has anticancer catekins (sic), which protect the cells from carcinogens, toxins, free radical damage, and help to keep radioactive strontium 90 out of the bones,” there’s no room left to describe the differences between tea styles, how to properly steep a cup, or any of the other subjects that I expected this whole book to be about.

Incidentally, none of those rather incredible health claims are footnoted, no studies are cited, and no backup data is provided.

All in all, this book is tailor-made for herbalists — especially those that don’t worry much about the scientific basis of their health claims — but pretty well useless for tea enthusiasts.

Rooibos: The African Red Bush

How have I been at this blog for so long without writing about rooibos? Oh, I know this blog is about tea, and I did write a post about green rooibos last year, but I haven’t covered straight red rooibos yet.

Rooibos comes from a bush called Aspalathus linearis, which grows in the west cape of South Africa. The name “rooibos” is from the Dutch word “rooibosch” meaning “red bush.” The spelling was altered to “rooibos” when it was adopted into Afrikaans.

Rooibos is also often called “red tea,” but most tea professionals shy away from that name for several reasons:

- The term “red tea” is used by the Chinese to refer to what we call “black tea.” No sense having two different drinks with the same name.

- Rooibos isn’t tea, since it doesn’t come from the Camellia sinensis plant. Instead, it is a tisane or herbal infusion.

- Rooibos only has that rich red color when it’s processed like a black tea. Green rooibos is more of a golden honey-colored infusion.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Rooibos is a tasty drink that is also good for cooking. Hopefully, I’ll have a chance sometime soon to write a review soon of the cookbook A Touch of Rooibos. I have been looking through it lately and it’s filled with interesting ideas. Generally, when used for cooking, the rooibos is steeped for quite a while and then reduced to a thick syrupy consistency. Unlike black tea, it can be steeped for ten minutes or more without becoming unpalatable and bitter.

Unlike “real” tea, which all has caffeine, rooibos is naturally caffeine-free. Since the flavor is similar to a mild black tea, this makes it a favorite bedtime beverage for many tea drinkers. Rooibos is also high in antioxidants.

Herbalists make many claims about the health properties of the rooibos tisanes. The Web site for the South African Rooibos Council (SARC), in fact, has very little information that isn’t in some way tied back to health claims. There are more and more studies being done, but available data are lacking in specifics (in my opinion, anyway) so I’m not going to quote any of those there. Feel free to check SARC’s site for lots of studies.

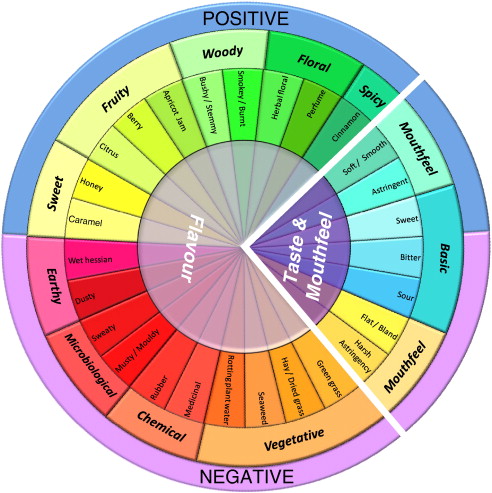

I don’t mean to imply that rooibos is only about the health benefits. It is, in fact, a very tasty drink. Most rooibos drinkers in the U.S. enjoy it straight or with a bit of sweetener (honey or sugar). In South Africa, it is commonly served with a bit of milk or lemon as well as honey. A group funded by SARC and Stellenbosch University has recently developed a “sensory wheel” for rooibos, describing both the desirable and undesirable aspects of flavor and mouthfeel. If you are interested in more information, click on the wheel below.

Rooibos Sensory Wheel as described in the article “Sensory characterization of rooibos tea and the development of a rooibos sensory wheel and lexicon,” available on Science Direct. Click the wheel above to view the article — there is a charge for the full text version.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Also, there is an article you can download in PDF format (click the thumbnail to the right to download) that describes the sensory wheel and the process used to create it.

Compared to tea, rooibos is a pretty small market. South Africa’s annual rooibos production is about 12,000 tons. That output is about equivalent to annual tea production of the Darjeeling region of India, or about a tenth of the tea production of Japan (the 8th largest tea producing country). Nonetheless, rooibos is important to South Africa, employing about 5,000 people and generating about $70 million in revenues.

The leaves of the rooibos bush are more like needles than the broad leaves of a tea plant. To produce red rooibos, the leaves are harvested, crushed, and oxidized using a process based on the one used in making Chinese black tea. Typically, the leaves are sprayed with water and allowed to oxidize for about 12 hours before being spread out in the sun to dry.

Green rooibos, as the name implies, is unoxidized or very lightly oxidized, and is processed more like a green tea.

For more information about the rooibos industry, I recommend the article Disputing a Name, Developing a Geographical Indication, from the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Tea and caffeine part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

This article is the second of a three-part series.

Part I: What is caffeine?

Part II: Exploding the myths

Part III: Decaf and low-caf alternatives

So you’ve decided you like tea, but you really don’t want (or can’t have) the caffeine. What are your alternatives?

Well, first there’s decaf tea. As Part I of this series explained, decaffeination processes don’t remove 100% of the caffeine, so this is a reasonable alternative if you want less caffeine, but not if you want none at all. There’s another problem with switching to decaf: the selection of high-quality decaffeinated tea is — let’s just say, limited.

It’s easy to find a decaf Earl Grey or a decaf version of your basic Lipton-in-a-bag. But if your tastes run more to sheng pu-erh, sencha, dragonwell, lapsang souchong, silver needle, Iron Goddess of Mercy, or organic first-flush Darjeeling, you have a problem.

You can try the “wash” home-decaffeination method, but I explained a couple of days ago why that process is overrated. You’re likely to be able to remove 20% or so of the caffeine that way, but that’s about it.

Another alternative is simply to brew weaker tea and/or use more infusions. Let’s do the math for an example. Assume you’re a big fan of an oolong that contains 80 mg of caffeine in a tablespoon of leaves, and you drink four cups of tea per day.

If you use a fresh tablespoon of leaves for each cup, and you steep it for three minutes, you will be extracting about 42% of the caffeine in each cup, which equals 34 mg per cup, or a total of 136 mg of caffeine for the day. If you shorten your steep time to two minutes, the extraction level drops to about 33% (total of 106 mg). Alternatively, you could use the leaves twice each time, so you’re extracting about 63% of the caffeine, but using a total of half as many leaves (total of 101 mg). Or, if you don’t mind significantly weaker tea, just use 1-1/2 teaspoons of leaves instead of a full tablespoon. Half the leaves means half the caffeine (total of 68 mg).

No caffeine at all

If you look through the selection of teas in a health-food store, you’ll notice that most of them have no tea at all, and the vast majority of those non-tea drinks have no caffeine. The problem is that chamomile for a tea drinker is like Scotch to a wine drinker; it’s just not the same.

There are a couple of beverages, however, that are somewhat similar to tea. Both come from South Africa and both are naturally caffeine-free.

Rooibos is often called “red bush” in the United States because the way it’s usually prepared leaves a deep red infusion. Typically, rooibos is oxidized (not fermented) like a black tea. It can also be prepared more like a green tea. I blogged about green rooibos last August if you’d like to know more about it.

North American news shows, along with people like Oprah and Dr. Oz, have been singing the praises of rooibos lately, bringing it more into the mainstream awareness. It is very high in antioxidants and much lower in tannins than a black tea. Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of independent research published about it yet, so many of the claims can’t really be backed up. The one that can be backed is that it has no caffeine and it tastes kind of like black tea (green rooibos is a bit grassy with malty undertones, more like a Japanese steamed green tea with a touch of black Assam).

Honeybush, like rooibos, grows only in South Africa. Also like rooibos, it is naturally caffeine-free and can be prepared either as a red or a green “tea.” When blooming, the flowers smell like honey, and honeybush tends to be somewhat sweeter than rooibos. Honeybush isn’t nearly as well-known as rooibos in the U.S., and the green version is very hard to find. I’ve found that if you want a flavored honeybush, citrus complements it very well. My “Hammer & Cremesickle Red” is the most popular honeybush blend in our tea bar (here is a blog post about it, and you can find it on the store website here).

A blended approach

If you like the idea of reducing your caffeine intake, but you don’t like the idea of a weaker tea (as I described above) or switching to rooibos or honeybush, you might want to consider blending. If you mix your tea half-and-half with something containing no caffeine, then you can still brew a strong drink, but get only half the caffeine from it. Combine that with the other tricks, like taking two infusions, and you can cut it even farther.

Tasting purple tea

Today, I received my first shipment of the purple tea that I blogged about back in August. I opened the bag with no preconceptions, as I haven’t read anyone else’s tasting notes.

The leaves look like pretty much any black tea. Not surprising, as the purple tea plant (TRFK306/1) can be prepared using any tea process, and this was oxidized like a traditional (orthodox) black tea. This is a very dense tea. The kilogram bag I purchased was the same size as the half-kilo (500g) bag of Golden Safari (a Kenya black I’ll be writing about soon).

I took a deep whiff, and picked up a slight earthiness to it that isn’t present in the other Kenya black teas I’ve tried. Not as extreme as a shu pu-erh, of course, as there was no fermentation in the process, but enough to distinguish the aroma from a traditional black tea.

Actually, despite my previous comment, I did come in to this with one preconception. Since this is a high-tannin tea, I expected a fair amount of astringency (“briskness,” as Lipton calls it), so I decided to take it easy on the first cup and make it like I make my 2nd-flush Darjeelings: 5 grams of leaves, 16 ounces of water at full boil, and a scant two-minute steep time.

“I did not expect purple, as the anthocyanin that gives purple tea its name doesn’t affect the color of black tea.”

The leaves settled immediately to the bottom of the pot, and I was taken by surprise by the color. I did not expect purple, as the anthocyanin that gives purple tea its name doesn’t affect the color of black tea. But I also didn’t expect the pale greenish tan color that immediately appeared (it later mellowed to a deep black with — you guessed it, a purplish tinge). We don’t have any analyses yet of total antioxidant content, but we know that the anthocyanin does contribute quite a bit.

My first taste of the purple tea was impressive. Rich, complex, and a bit more astringent than you’d expect with only a two-minute brewing time. The earthiness in the aroma comes through subtly in the taste, and there’s a silky mouthfeel that lingers on the back of the tongue.

I figured that there was enough going on in that tea that it could hold up to a second infusion, so I brewed a second cup off of the same leaves. This time I gave it a three-minute steep, and it came out tasting very similar to the first brew, although a bit more pale in color.

“Purple tea is certainly not cheap.”

All in all, I’m pleased and excited to have this new varietal available at the tea bar. Purple tea is certainly not cheap. At $16.00 per ounce, it’s one of the priciest teas on our menu, but I expect it to build a fan base quickly. Our new tea website isn’t quite ready to launch yet (I’ll make a big announcement here when it is), but if you’d like to order some Royal Purple tea, just call the store (406-446-2742) or send an email to gary (at) redlodgebooks (dot) com. We’re ready to ship right away.

UPDATE MAY 2012: Our tea website is up and running, and Royal Purple tea is now available for purchase.

More more information about purple tea, please see my earlier blog post announcing and describing the varietal.

Copywriters and tea marketing experts

These days, you can’t be too careful what you say on a tea website. Last year, Unilever was warned by the FDA for claims they made about “Lipton Green Tea 100% Natural, Naturally Decaffeinated.” A week later, they warned Dr. Pepper Snapple Group about claims they made concerning “Canada Dry Sparkling Green Tea Ginger Ale.” Earlier this year, the FDA’s target was Diaspora Tea & Herb (d.b.a. Rishi Tea) for a wide variety of health claims on Rishi Tea’s website.

Given these warning shots fired across the bows of the big boys, the whole industry is being careful about making nutritional claims for tea. But we still need to say more about tea than just “this stuff tastes really, really good” — although that’s generally good enough for me.

For an example of how far companies are going these days, we got a promotional mailer today from Numi Tea. They are a fine company, and I’d be happy to resell some of their products in our tea bar. The mailer has some traditional marketing language (with appropriate footnotes, of course), just as I’d probably write myself:

“[Pu-erh]’s unique fermentation process results in more antioxidants than most green teas and is traditionally known to help weight management*, improve digestion and naturally boost energy.”

Well, I hope I wouldn’t write it exactly like that, but given a bit of tweaking to the grammar and punctuation, it’s a reasonable sentence.

The first claim is footnoted “*Along with a healthy diet and exercise.” Okay. I’ll buy that. Given enough healthy diet and exercise, lots of things help with weight management. The other two claims are very difficult to measure and/or prove. Vague claims typically don’t draw the ire of the FDA, so they’re probably safe.

But it was the next section that made me chuckle. It says, and I quote:

“Every blend is freshly brewed, made with full-leaf tea and uses 100% real ingredients for a pure Pu-erh tea taste.”

Wow! It uses 100% REAL INGREDIENTS! Is that the best they could do? Really? Can you imagine the certification process for that? “Is this an ingredient? Yep!” I carry 100 different teas in my tea bar, and I can guarantee you that every single one of them carries 100% real ingredients. Yep. Not an unreal ingredient in the bunch.

I did a bit of further looking, and found that the front cover of their mailer says, “Real ingredients. 100%. Nothing else.” There’s a whole section of their website called “100% real ingredients.” There’s a paragraph on that page of their site that says:

“For a pure, authentic taste, we blend premium organic teas and herbs with only real fruits, flowers and spices. We never use ‘natural’ flavorings or fragrances like other teas do.”

I’m pleased to hear that they only use “real” ingredients, and not “natural” ones like everyone else. Come on, Numi. You make some absolutely fantastic teas, and your organic and fair-trade programs are excellent. I’d like to see you spend more time talking about that — which really does differentiate your products — and less time talking about being “real,” which means absolutely nothing.

I’ll have a green red tea, please

I’ve been drinking rooibos (a.k.a. “African redbush,” a.k.a. “red tea”) for years, and stocked our tea bar liberally with varieties of it. All of them use the same base plant — Aspalathus linearis — prepared with an oxidation process similar to what’s used for black tea. The plant is naturally caffeine-free, which is a great boon for those of us who aren’t fans of chemical or pressure decaffeination techniques.

In green rooibos, the leaves (shaped like needles) are heated after picking to stop the oxidation process and keep the green color and mild flavor.

Rooibos has developed quite a following, especially with all of the press it’s been getting for being high in antioxidants. Only recently, however, have requests started coming in at the tea bar for “green” rooibos.

I am in the tea business because I love the flavors of tea. I’m not an herbalist, so everything I do with tea starts with the taste. I ordered in some green rooibos for the tea bar, and gave it a try. Green rooibos has minimal tannin content, so bitterness isn’t a danger. For my first try, I made a cup using 195-degree water (I’m at 5,500 feet altitude, so that’s about 7 degrees below boiling), and steeped it for 5 minutes. I used one tablespoon for a 13-ounce cup, and did not add anything (no lemon, sugar, milk…).

The first thing I noticed was the color. The liquid is a beautiful golden honey color, quite different both from most green teas and from the traditional red rooibos. The tea is smooth and woody, with just a hint of grassiness and nut flavor. True to promise, there’s no bitterness at all, and no need for additives. Just to push the limits, I re-used the leaves, steeping them for 10 minutes this time. The flavor and aroma were almost identical to the first cup.

There are a lot of claims out there about green rooibos being significantly higher in antioxidants than traditional red rooibos. A quick perusal of the research still shows mixed results on that, so I’m not going to take a position on the health effects. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m in it for the taste!

While writing this, I realized that I had tried it hot, but not iced. The folks over at Suffuse Rooibos say green rooibos makes a fantastic iced tea, so I took a break to make a cup of iced green rooibos (the research is the best part of this job!). I brewed it the same way (5-minute steep time), and poured it directly over a cup of ice cubes — again, I didn’t add anything to it. I found it refreshing and tasty; excellent for a hot day when I don’t want to overload with caffeine. I will definitely be drinking more of this!